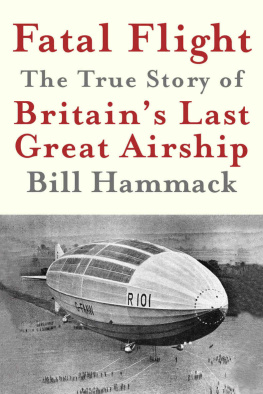

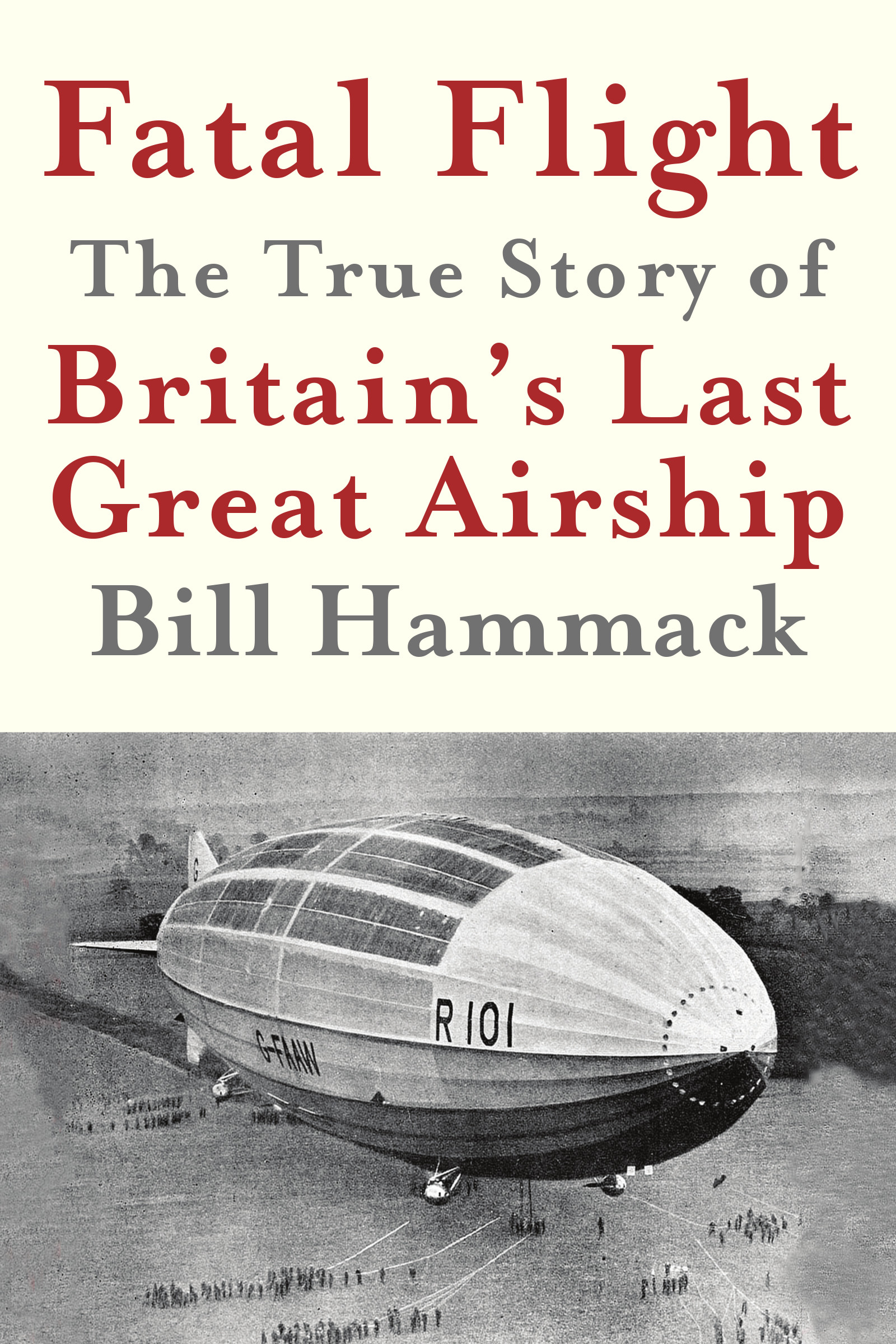

Fatal Flight

The True Story of Britains

Last Great Airship

Bill Hammack

A fascinating story , not nearly well enough known on the American side of the Atlantic, artfully and engagingly told . G.J. Meyer New York Times bestselling author of A World Undone: The Story of the Great War 1914 to 1918 & The World Remade: America in World War I

Why does brilliant vehicle design sometimes end in tragedy? The crash of the intended flagship of the British Empire, the magnificent dirigible R.101 , is not only an absorbing human and technical story as told by Bill Hammack. It is also a vital lesson in the risks of even apparently small compromises and unforeseen hazards to big projects when confronted by the forces of nature. Impressively documented, Fatal Flight should be required reading for engineers and political leaders alike. Edward Tenner Author of international bestseller Why Things Bite Back & Our Own Devices

A well-researched and gripping look at Britains greatest airship disaster from a new perspective: through the eyes of a man who built, flew, and died with the ship. Dan Grossman, Airship Historian author of airships.net and coauthor of Zeppelin Hindenburg: An Illustrated History of LZ

Other Books by the Author

Why Engineers Need to Grow a Long Tail

Bill Hammack 2011

How Engineers Create the World

Bill Hammack 2011

Eight Amazing Engineering Stories

Bill Hammack, Patrick Ryan, & Nick Ziech 2012

Albert Michelsons Harmonic Analyzer

Bill Hammack, Steve Kranz, & Bruce Carpenter 2014

Michael Faradays The Chemical History of a Candle

Bill Hammack & Don DeCoste 2016

Copyright 2017 William S. Hammack

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission from the publisher.

Articulate Noise Books

New York | info@articulatenoise.com

First Edition: June 2017

William S. Hammack

Fatal Flight: The True Story of Britains Last Great Airship / Bill Hammackst edition (version 1.0 )

ISBN 978-1-945441-01-1 (hbk)

ISBN 978-1-945441-02-8 (electronic)

ISBN 978-1-945441-03-5 (pbk)

. R101 (Airship).. AirshipsGreat BritainHistory.. AirshipsHistory20th century.. Aircraft accidents.. AirshipsDesign and constructionHistory. I. Title.

Never to lose an opportunity of reasoning against the head-dimming, heart-damping Principle of Judging a work by its Defect, not its Beauties. Every work must have the formerwe know it a prioribut every work has not the Latter & he therefore, who discovers them, tells you something that you could not with certainty or even with probability have anticipated .

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Coleridges Notebooks: A Selection , ed. Seamus Perry (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002 ), p.

Contents

List of Illustrations

Relative Sizes of the Hindenburg , Graf Zeppelin , HMA R.101 , and USS Akron page

Inside His Majestys Airship R.101 page

R.101 s Proposed Route to India page

The Mooring Tower at the Royal Airship Works page

Route of R.101 on its First Flight over London page

The First Forty-Five Minutes of R.101 s Final Flight page

Route of R.101 s Final Flight page

Prologue

The Perennial Promise of Airships

A t four in the afternoon on Wednesday, October , 2015 , a Pennsylvania State Police officer fired a hundred shotgun blasts into the nose of a runaway blimp. The milk-white blimp , caught in a tree, sank to the ground as helium whistled from the shotgun holes. As the helium leaked, a team from the United States Army rolled up the blimps tail, which had separated when it crashed. From the tail a 6,700 -foot Kevlar tether snaked across the rugged, wooded terrain. A team cut the tether with carbon-steel-bladed scissorsKevlar is used for bulletproof vestsinto small sections, which another team loaded onto a truck.

Four hours earlier, the blimp had broken free of its mooring at the Armys Aberdeen Proving Ground near Baltimore, Maryland. Although designed to always be crewless and tethered to the ground, the -foot-long blimp had traveled miles north, crossed into neighboring Pennsylvania, and dragged its mile-long tether along the ground, terrifying local residents. Fortunately, no one was injured or killed. The whip-like cable, however, destroyed two million dollars worth of power linesa pittance compared to the now-destroyed blimps $ million cost.

The escaped blimp was part of the $ 2.7 billion Joint Land Attack Cruise Missile Defense Elevated Netted Sensor System ( JLENS ). It held aloft a radar high enough above the horizon to detect cruise missiles, drones, and other low-flying weapons. Despite its high price tag, the Pentagon rated JLENS as poor in reliability, unable to provide twenty-four-hour surveillance. It was labeled as fragile, Pentagon-speak for did not demonstrate the ability to survive in its intended operational environment. Critics called it a zombie government program: one that feeds on cash and is impossible to kill. It survived with the same justification used by proponents of lighter-than-air craft who aspired to create more than a novelty like the Goodyear blimp or the mere utilitarian and humble weather balloon. The wayward military blimps promoters promised that this newest version of a lighter-than-air craft would solve one of the most pressing problems of our time. The JLENS blimp would watch the skies and sound the alert at the first hint of an aerial attack from a rogue group or nation.

The front-page news of the runaway JLENS blimp was just that: news to almost all Americans and others around the world. Who knew we used lighter-than-air craft for anything besides covering the Super Bowl or golf tournaments? To several generations, an airship means a zeppelin, and their image is of the Hindenburg burning in the sky. Yet airships have a rich history beyond that of the iconic zeppelin.

The story of lighter-than-air craft is one of empire and national pride, of technological advances and human perseverance, of ego and bravery. While the story of winged flight is prominently part of every history textbook, that of lighter-than-air craft, though more glorious and tragic, is largely untold in the modern day. In their heydaybetween the First and Second World Wars and before transcontinental airplane flightairships the size of the Titanic were the preferred method of travel between continents.

The allure of lighter-than-air craft to solve pressing problems can be traced back for decades. In 1997 , six years after the first web page was posted, a company called Sky Station solicited $ 4.2 billion to built antenna-equipped blimps to deliver Internet service. In May 1985 , the British Antarctic Survey revealed a hole in the ozone layer over the South Pole, and a few years later a professor suggested sending blimps that dangled electrical wires to zap ozone-eating chemicals. In the 1970 s, the Aereon Corporation proposed a hybrid lighter-than-air craft that would take off like a jet, then float like a blimp. This aerial workhorse would inexpensively usher all nations into the twentieth centuryno need for costly infrastructure such as roads, railroads, tunnels, bridges, airports, warehouses, or harbors. In the 1950 s and s, when nuclear fuels promised unlimited energy, a Boston University professor proposed a nuclear-powered version of the airship.