Fonthill Media Limited

Fonthill Media LLC

www.fonthillmedia.com

First published in the United Kingdom and the United States of America 2015

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data:

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Copyright Malcolm Fife 2015

ISBN 978-1-78155-281-0

The right of Malcolm Fife to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in

accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise,

without prior permission in writing from Fonthill Media Limited

Typeset in 10pt on 13pt Sabon

Printed and bound in England

Contents

Acknowledgements

I give special thanks to the following for assistance with this book: Mick Davis, Editor of the Cross and Cockade journal, who checked for factual errors and allowed me to use his plans of airship stations; Ross Dimsey, for editing the manuscript; Brian Turpin, for validating the factual content of the text; and Bob OHara, for research in the Public Records Office.

Finally, I would also like to acknowledge the helpful contributions of the following: Giles Camplin, the Airship Heritage Trust; Kenneth Deacon; Andrew Dennis, Assistant Curator of the RAF Museum; George Edwards, local and family history librarian in Haverfordwest; Jim Eunson; Clare Everitt, Picture Norfolk; Jon Excell, Editor of The Engineer; Kevin Heath, the Aviation Research Group in Orkney and Shetland; Steve Jackson, Library and Archives Senior Assistant at the Manx Museum; Paul Johnston, Image Library Manager of the National Archives; Alan Johnstone; Nigel Lutt, Archives/Ops Manager of the Bedfordshire and Luton Archives; Julie Mather and Emily Weeks, Research Assistants at the Fleet Air Arm Museum; Guy Mather; Vinit Mehta, the RAF Museum; Derek Millis, the Airship Heritage Trust; Graham Naylor, Senior Librarian at the Plymouth Central Library; David Ratcliffe; Linda Rhodes, Local Studies librarian at the Heritage Services in Barking; Sally Richards, the Imperial War Museum Picture Library; Brian Riddle, Chief Librarian at the National Aerospace Library; Pat Roland; Sabine Skae, the Dock Museum; Peter Tamaqua, Library and Archives Assistant at the Science Museum; Paul Ternent, Senior Archives Assistant at the Northumberland Archive Service; Janet Tierney, Curator of Goole Museum; Sonya Waplington, the Cumbria Archives; Guy Warner; Peter Wright, Cross and Cockade.

Preface

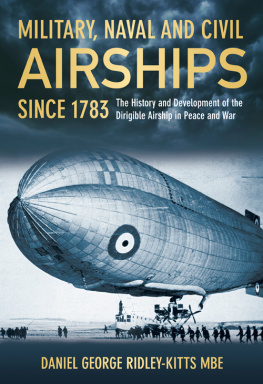

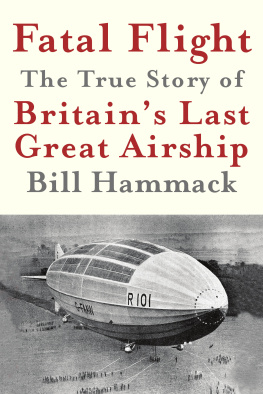

There are few inventions that have captured the imagination like airships. First flown at the end of the nineteenth century, they evolved within a span of less than fifty years to become the largest flying machines ever seen. Some were over twice the length of the largest passenger jets of the early twenty-first century. Few of those who witnessed these leviathans of the air in flight would forget the experience.

The career of the airship was remarkably brief, lasting little more than half a century: by the end of the Second World War, the species had become almost extinct. There have been numerous attempts to revive it, but most have, at best, met with only very limited success. Airships now live on in novels, action films, and advertisements.

One of the drawbacks of operating large airships in the early twentieth century was the need for complex supportive infrastructure on the groundlarge sheds to house them, hydrogen plants to supply them with gas, and workshops for construction and repairs. In fact, so dependent were large airships on accommodation to protect them from the elements, that the availability of such structures to some extent dictated airship policy. In the latter stages of the First World War, several enormous airship shedsrivalling even cathedrals in sizewere constructed in Britain. They were built in a short space of time, and mostly lasted no more than five or six years.

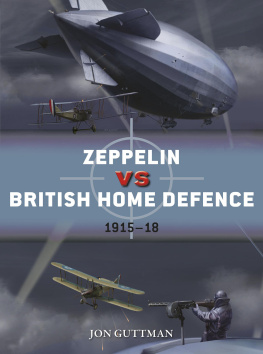

Far easier to house were the non-rigid airships operated in large numbers by the Royal Navy in the First World War. They were much smaller than the 500-to-600-foot-long rigid Zeppelin airships in German service, being around 200 feet in length. These consisted of a bag of gas, known as the envelope, under which was suspended a control car containing the power plant and crew. Over 200 such machines served in the Royal Navy Air Service, as opposed to only a handful of rigid airships, but it is the latter type which most people think of when the word airship is mentioned.

While there have been numerous publications on airfield histories, only a small number are devoted to airship stations. Peter Wright was responsible for a three-part article on Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) airship stations, which appeared in the First World War aviation magazine Cross and Cockade in 20012 and dealt mainly with the buildings at each location. This book is the first to detail all locations used by British civil and military airships, and is intended to give the uninformed reader a depiction of the activities at each station. Where possible, the research has been based on original records and contemporary newspaper articles. Finally, it should be noted that when the RAF was formed on 1 April 1918, it inherited the personnel and aeroplanes of the RNAS. Hence, the prefix RNAS has been dropped from the names of airship stations after this date, although they still remained the property of the Admiralty.

1

The Airship Pioneers

If the more sensational claims are to be believed, airships are as old as civilisation itself. Col. Lockwood Marsh, a secretary of the Royal Aeronautical Society in the early 1920s, claimed to have discovered the earliest reference to them in an ancient Abyssinian manuscript. According to him, it describes a flying machine resembling an airship which King Solomon presented to the Queen of Sheba, a vessel wherein one could traverse the air (or winds) which Solomon had made by the wisdom that God had given unto him.

In the thirteenth century, Roger Bacon, a Franciscan Friar who spent much of his time carrying out scientific experiments, thought that human flight could be achieved by filling a thinly walled metal sphere with rarefied air or liquid fire. Fanciful ideas on how man could break free from his earthly domain flourished in the following centuries. Francesco Lana de Terzi, a professor of Physics and Mathematics at Brescia, Italy, detailed a proposal for a vacuum airship in his book Prodromo in 1670. His lighter-than-air vessel would be shaped like a small ship with four thin foil copper spheres pumped to vacuum conditions attached to it. Once the craft became airborne, a sail would be used to propel it in the same manner as a sailing ship. However, Francesco Lana de Terzis vacuum airship never left the page. He was aware that such an invention could be used as a weapon of war and naively wrote:

God would not suffer such an invention to take effect, by reason of the disturbance it would cause to the civil government of men ... it may over-set them, kill their men, burn their ships by artificial fireworks and fireballs. And this they may do not only to ships, but to great buildings, castles, cities.

Jean Baptiste Marie Meusnier, an officer in the French Engineer Corps, is credited with creating the first practical design for an airship in 1784. It was an elongated balloon driven by propellers. Early in the nineteenth century, Sir George Cayley, the 6th Baronet of Brompton, further refined these ideas. He is regarded as one of the founders of Aeronautics, for he was the first person to understand the principles of flight. After designing and building a number of model gliders, he turned his attention to airships, and by 1816 had designed a streamlined airship with a semi-rigid structure, and later, one powered by a steam engine. While Sir George Cayley went on to construct and fly gliders which could lift a man, his airships remained firmly on the drawing board. A major drawback was that there were no lightweight power plants available at the time to transform a balloon into an airship. The only power plant available was the steam engine, and as well as adding considerable weight to any lighter-than-air craft, the sparks produced by its combustion process could set fire to the hydrogen-filled envelope.