First published in Great Britain in 2019 by

Pen and Sword Transport

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Anthony Burton, 2019

ISBN 978 1 52671 949 2

eISBN 978 1 5267 1 951 5

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52671 950 8

The right of Anthony Burton to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Books Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing, Wharncliffe and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

C HAPTER O NE

Taking to the Air

Man it seems has always dreamed of flying. Every culture has stories of unlikely winged creatures, from the angels of Judaic and Christian tradition to the feathered gods of the Aztecs. There are even stories of flying machines being built in the ancient world, such as the vimanas of India, mentions of which were found in a Sanskrit manuscript though it didnt surface until the nineteenth century. These amazing machines were said to be capable of great speeds and of travelling off to distant planets. Mythology also has its stories of human attempts to take to the skies, of which the most famous is the story of Icarus. He tried to fly with feathery wings held together with wax but became overconfident. He flew too near the sun, the wax melted and he plunged to his death. All these stories are very ancient, but it is not until much later that we find actual attempts by real people to emulate the birds.

Factual accounts are rather scarce, but it seems all the earliest attempts at flying involved an Icarus-like idea of making wings, sometimes even using bird feathers and then launching into the air from some high building or cliff, usually with spectacularly bad results for would-be aviators. The Chinese appear to have started things off, when the Emperor Wang Mang ordered one of his men to don wings and leap from a tower in the first century AD and he is reported as having glided down covering 100 yards on the ground, rather more a controlled fall than an actual flight. In the sixth century another Chinese emperor repeated the experiment with another of his servants: there are no records of these gentlemen trying out their own inventions.

Europeans were a little slower in developing a taste for feathered leaps from towers. The most successful attempt happened at Cordova in Al-Andalus in the ninth century. Abbas Ibn Firnas studied science and developed some form of flying machine, of which no details are known, but he was able to take off from a hilltop in 875 and reports say he remained aloft for an impressive ten minutes. Unfortunately, the landing was less successful and he injured his back quite severely and never attempted another flight. In England, the honour, if that is the word, of attempting to fly goes to a monk of Malmesbury Abbey. The flight was recorded in a work written by William of Malmesbury, and tells how a young monk, Elmer, watched jackdaws flying round the abbey and gliding on air currents. He felt that if equipped with wings he could do the same actual details of his wings were not recorded. But the records do show that in 1010 he leapt off a tower the present abbey had not yet been built and glided for some 200 yards before crashing and breaking both his legs. He considered another attempt, this time with a tail for stability, but the Abbot forbade it and that brought attempts at gliding off towers to an end until the sixteenth century, when there was a brief revival. In 1507, John Damain jumped from the walls of Stirling Castle with the predictably disastrous result, which he blamed on using chicken instead of eagle feathers.

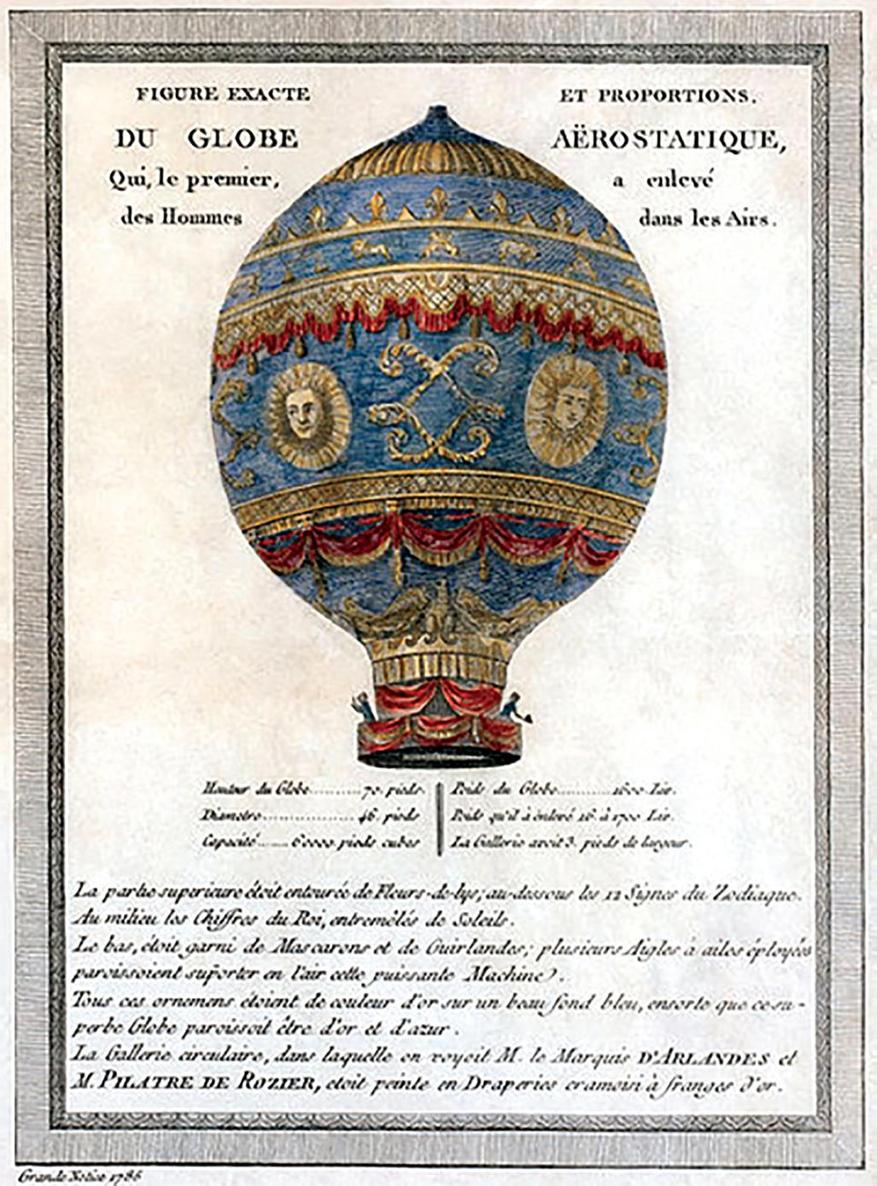

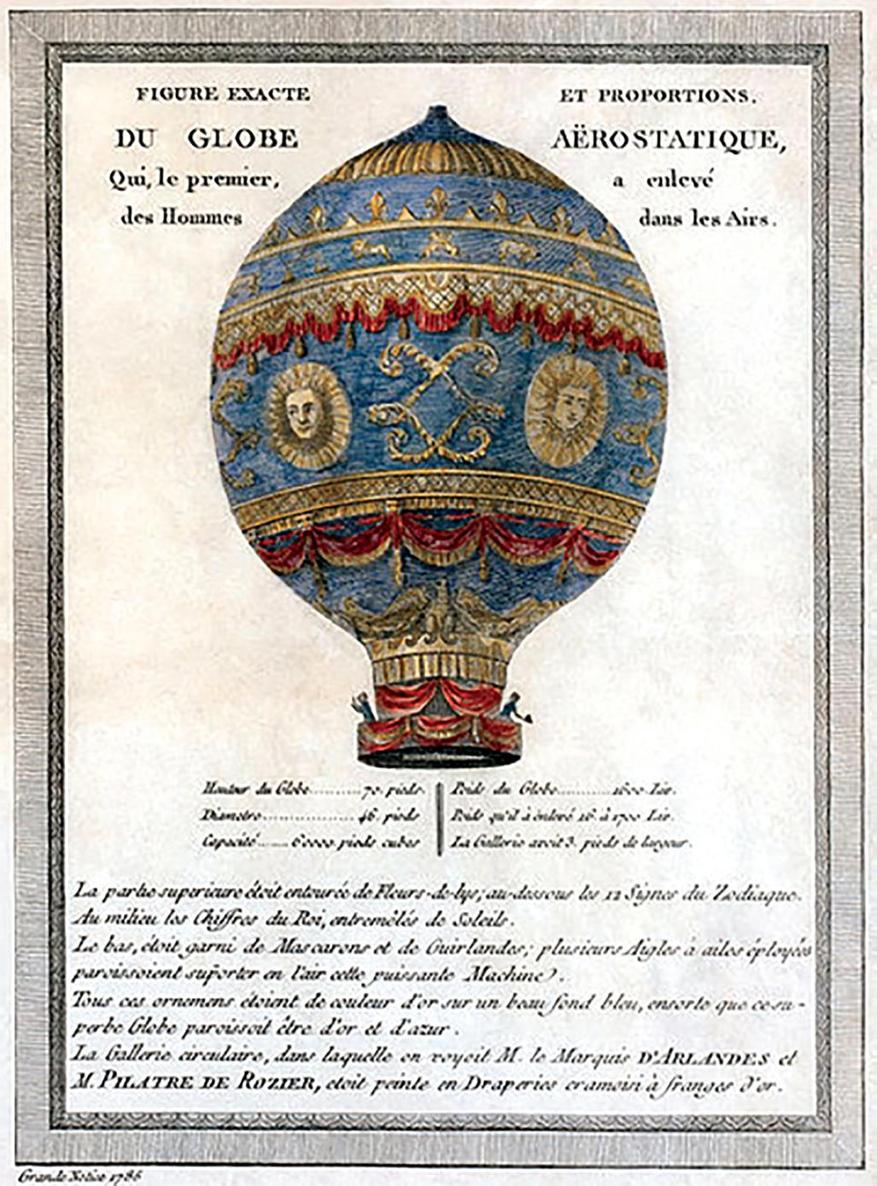

The Montgolfier brothers were the first to manufacture hot air balloons, and on their public flights they made sure they were not ignored by decking them out in bright colours.

There were various attempts during the Renaissance to invent flying machines, notably by Leonard da Vinci, who wrote about and sketched many different versions including an early version with a rotary screw, a sort of primitive helicopter. None was actually put to the test; the problem was the one that had plagued all early would-be aeronauts: a lack of appropriate power. Unlike birds, the muscles of Homo Sapiens are not adapted for flight. How was man to get off the ground? The answer already existed in China and had done so since at least the third century BC, when they made flying lanterns, devices we still have today and simply know as Chinese lanterns. A small lamp is placed at the bottom of a paper balloon and as the air in the balloon heats up, it rises because the hot air is lighter than the surrounding atmospheric air. Chinese lanterns are simply small hot air balloons. The idea was first shown in Europe by a priest, Bartolomeu de Gusmo, who made a paper balloon with a light underneath and demonstrated it lifting in the air at the royal court in Lisbon in 1709. No one seems to have thought that a larger version might fly with a human passenger. That vital step had to wait until nearly at the end of the 18 th century and the work of the most famous men in ballooning history, Joseph-Michael and Jacques-Etienne Montgolfier.

The Montgolfier family had a long tradition of paper making. The process had first been developed in the Far East, but by the Middle Ages had reached as far as Damascus. One of the Montgolfier family was captured during the sixth crusade, a misfortune that actually helped establish the familys fortune, for it was during this time that he learned the secrets of paper manufacture. Once he was freed he returned to the family home at Ambert in the Auvergne in 1386 where he built a paper mill. He was followed by others and the local river was soon supporting a chain of mills, one of which still survives, working just as it was in the fourteenth century, with a waterwheel supplying the power. In 1693 two Montgolfier brothers, Michael and Raymond, married the two daughters of Antoine Schelle who owned mills in Annonay some 70 miles from Ambert, which the Montgolfiers soon turned to paper making. This was a decisive moment in their fortunes. The mills prospered to such an extent that they were able to add the proud claim of being officially royal manufacturers. By the middle of the eighteenth century, control had passed to Pierre Montgolfier, and it was his two sons, Joseph, born in 1740 and Etienne, five years later, who were to add fame to fortune.