Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

For Lara

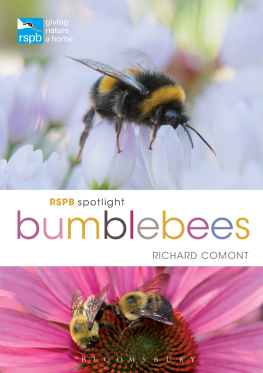

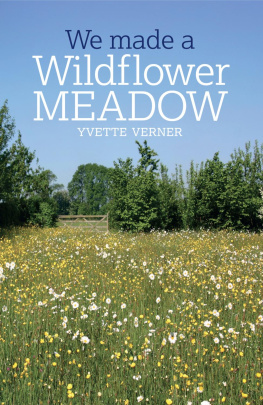

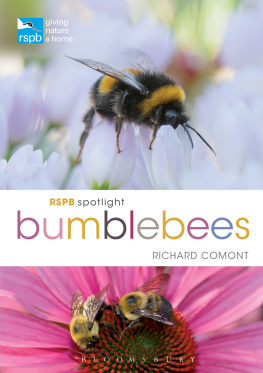

In 2003 I bought a derelict farm deep in the heart of rural France, together with thirteen hectares of surrounding meadow. My aim was to create a wildlife sanctuary, a place where butterflies, dragon-flies, voles and newts could thrive, free from the pressures of modern agriculture. In particular I was keen to create a place for my beloved bumblebees, creatures I have spent the last twenty years studying and attempting to conserve. This book, in part, is the story of this little corner of the French countryside, of the plants and animals that live there, of their natural history, and of my efforts to encourage them. Most natural-history documentaries and much conservation effort focus on large, charismatic animals: whales, pandas, tigers, and so on. One of my aims in writing this book is to inspire an appreciation for the smaller, everyday creatures that live all around us the insects and their kin. As chance would have it, many of the insects and flowers that have colonised the farm are species that I myself have studied over the years in my scientific career, and I explain some of the research that has been carried out to explore their secret lives. You will learn how a death-watch beetle finds its mate; about the importance of flies; how some flowers act as thermal blankets for bees; and about the complex politics of life as a paper wasp, amongst much else. In telling these stories perhaps I can also convey to you the fun of discovery, the satisfaction to be had in teasing apart the details of the lives of the creatures with which we share our planet. More importantly, I want you to realise that what we know and understand about natural history is just the tip of the iceberg. Even among the creatures that inhabit this single meadow, there is no doubt a near-infinite number of beguiling mysteries that have yet to be explained, animals that have never been studied, behaviours that have not yet been observed. What wonders have still to be discovered?

In the second part of the book I show you how the lives of the creatures in the meadow are interwoven with each other and with the wild flowers. Plants compete for space, water and light, are food for herbivores, hosts to parasites and diseases. They use diverse strategies to tempt pollinators to visit them, and in turn their pollinators have evolved numerous tricks so that they can learn which flowers are most rewarding and can gather those rewards quickly, sometimes robbing their hosts, at other times being duped into pollinating flowers for no reward. Plants depend on a horde of small animals and microorganisms to break down leaves and dung to release their nutrients, and they benefit from the actions of predatory birds, spiders and insects that keep down the numbers of caterpillars, grasshoppers and greenfly that might eat their leaves. Every species is linked, one way or another, to hundreds of others, in a web of interactions that are at present far beyond our ability to fully comprehend.

In the final part, I explain how the modern world has become increasingly inhospitable for wildlife, as humans squeeze ever more from the land to provide for our many needs. I give some examples of the devastation we have caused and are causing to our planet, from the effects of primitive mans prehistoric spread out of Africa to the insidious damage that we continue to do through our overuse of poisonous chemicals in the countryside. Many of the fascinating creatures with which we share our world are slowly disappearing as a result of our actions, often before we have learned a single thing about their lives, or of their role in the tapestry of life. This book is intended as a wake-up call, to remind us that we should cherish life on Earth in all its forms. As species become extinct, so the mysteries of their lives are lost for ever. We are destroying our childrens inheritance, stealing from them the joy of discovery and exploration of the natural world. What is more, we are undermining the ability of our planet to support us; although we understand very little about the myriad complex interactions between the many creatures on this Earth, we do have good evidence to suggest that these interactions are vital to the health of the planet, and hence are vital for our own well-being and perhaps for our very survival.

I want to make you look at our world with new eyes; to persuade you to go out into your garden or a local park and get down on your hands and knees and look . There is so much to see. If you look closely enough, you cannot fail to begin to appreciate the precious undiscovered glory that is life on planet Earth. If we learn to value what we have, then perhaps we will find a way to keep it.

We inhabit a spherical rock, just 13,000 kilometres miles across, floating in the unimaginable vastness of space. It is at least ten thousand billion kilometres to the nearest planet that might possibly support any other life, a distance of which our brains cannot begin to conceive. We spend much time and effort on building telescopes that can look ever further into the void, and on listening to and analysing radio waves from distant galaxies, in the hope of detecting signs of other life forms. Many films, TV shows and novels speculate about what might be out there. Yet there are real wonders of the universe right here, all around us, and we pay them little heed. We are lucky enough to share our little rock with perhaps ten million different species, and many of them have not yet even been given a name.

I am fortunate enough to own a small hay meadow in rural France. Being something akin to the entomological equivalent of a train-spotter, I have so far identified more than seventy bee species, fifty types of butterfly, sixty bird species and well over 100 different flowering plants living in this meadow. This is just a small fraction of the grand total; I have not yet begun to tackle the springtails, mites, worms, spiders, beetles, snails and other creatures that live there, and in all likelihood I will never find time. The vast majority of the creatures that we ignore are small, many so diminutive that they can barely be seen with the naked eye, and others much smaller still. But if you take the trouble to place one of these minute creatures under a microscope you will reveal their precise symmetry and exquisite structure. Each and every one has a different story, a life history; it must find food, grow, evade predators, find and court a mate, lay eggs, and so on. Every step involves challenges, obstacles that must be overcome, and every species has evolved its own unique combinations of strategies to survive and thrive; if it had not, it would long since have disappeared. Even in western Europe, where we have a long tradition of studying natural history, we know almost nothing about the lives of most of these wild creatures.

In this section I will introduce you to some of the insects and other small animals that live in this meadow, to some of the very few that have been studied at least a little, and to what is known about some of their relatives that live in more exotic climes. I will try to explain some of the fascinating details of their behaviour and ecology, what roles they play in the ecosystem, and my own efforts to encourage more and more species to colonise this little corner of the French countryside. Welcome to the meadow