Bloomsbury Natural History

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

| 50 Bedford Square | 1385 Broadway |

| London | New York |

| WC1B 3DP | NY 10018 |

| UK | USA |

www.bloomsbury.com

This electronic edition published in 2017 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published 2017

Copyright 2017 text by Richard Comont

Copyright 2017 photographs and illustrations as

Richard Comont has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data has been applied for.

ISBN: 978-1-4729-3361-4 (PB)

ISBN: 978-1-4729-3363-8 (eBook)

ISBN: 978-1-4729-3362-1 (ePDF)

Design by Rod Teasdale

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

For all items sold, Bloomsbury Publishing will donate a minimum of 2% of the publishers receipts from sales of licensed titles to RSPB Sales Ltd, the trading subsidiary of the RSPB. Subsequent sellers of this book are not commercial participators for the purpose of Part II of the Charities Act 1992.

Contents

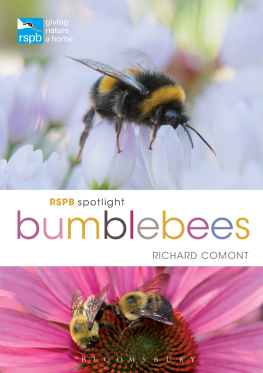

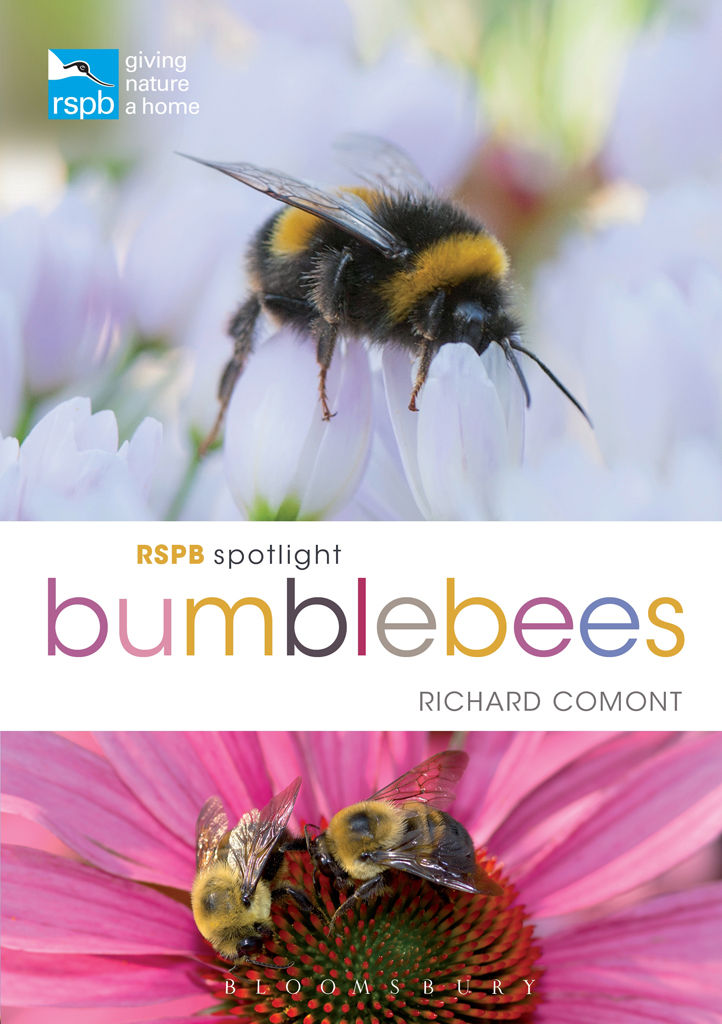

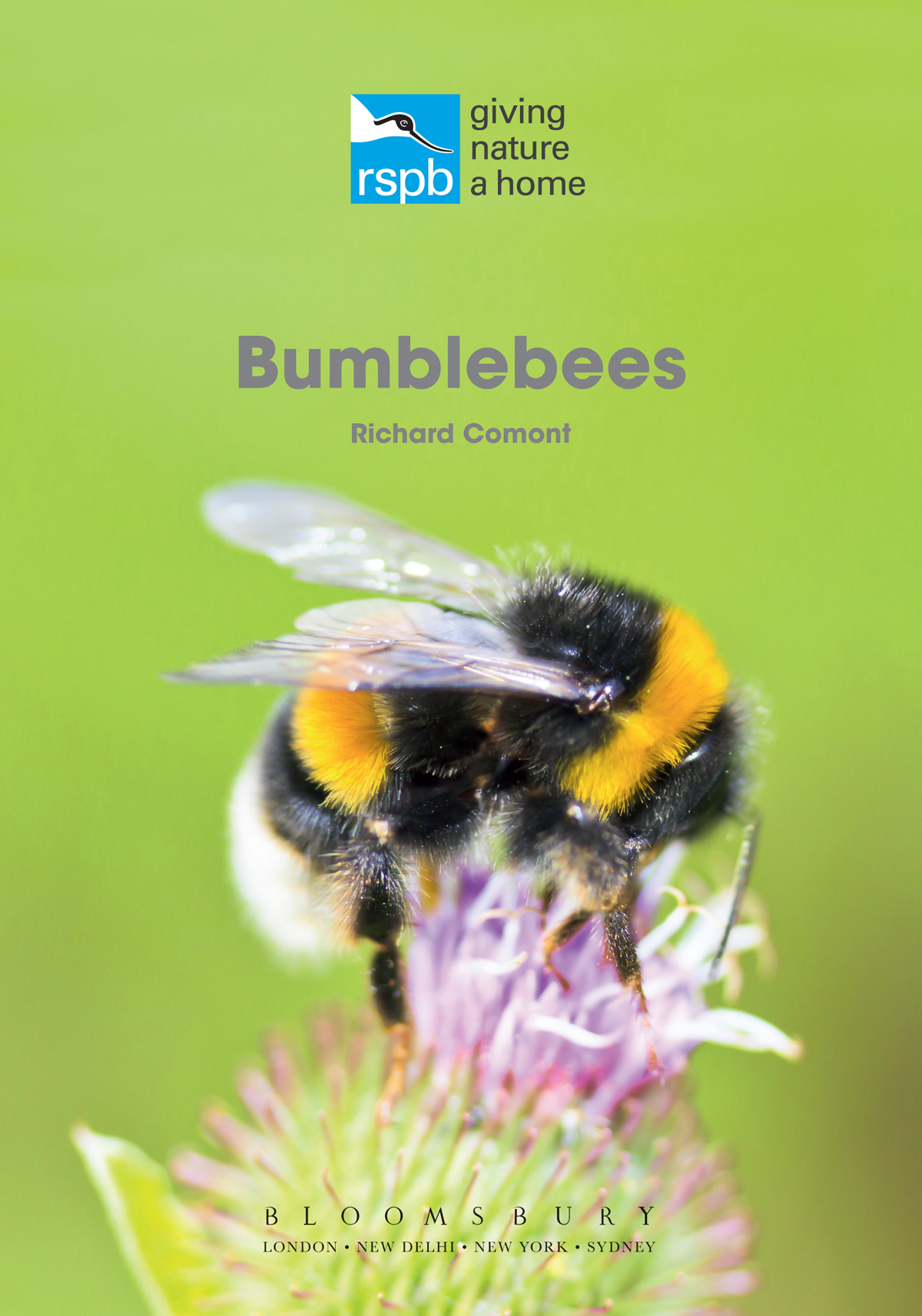

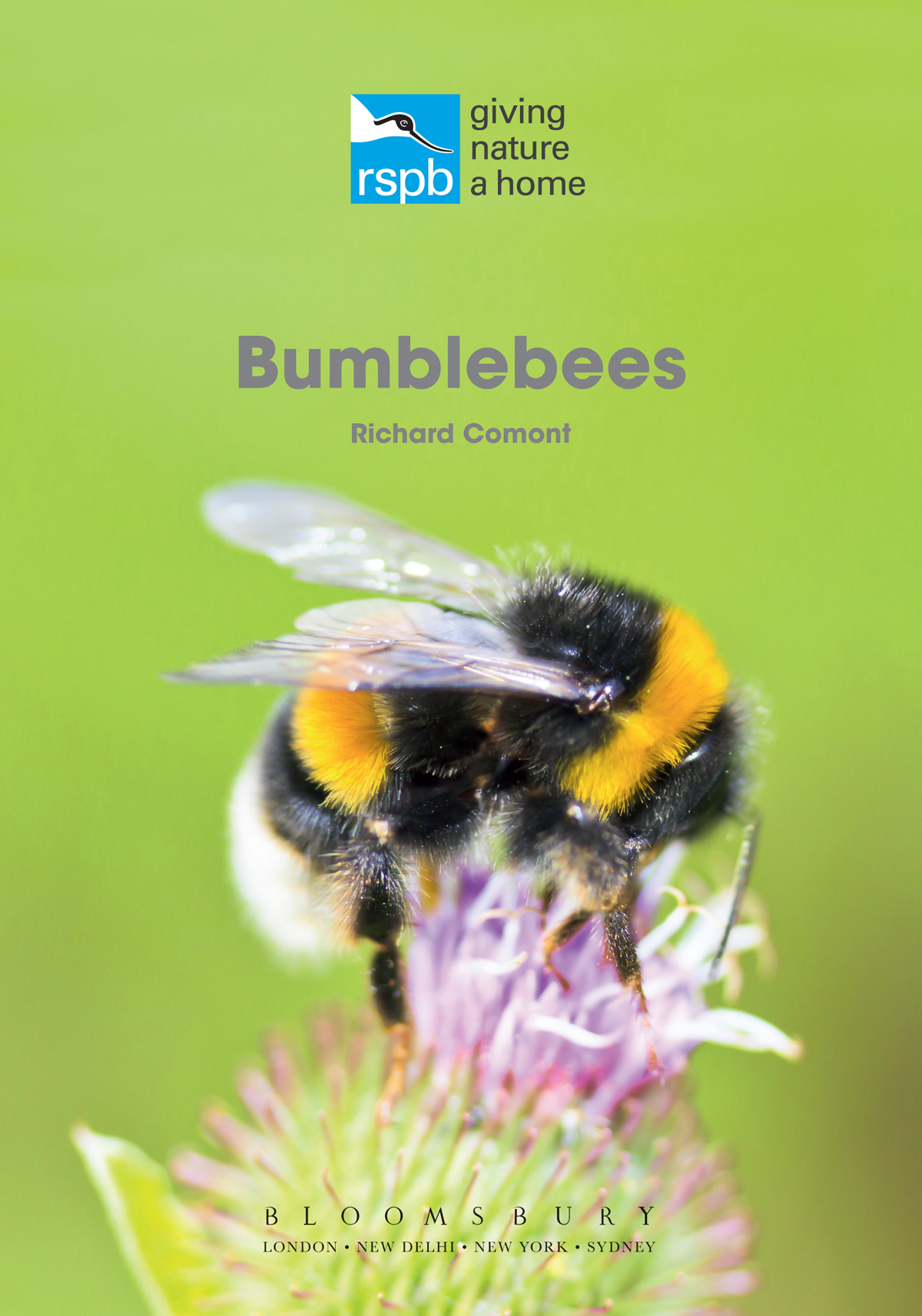

Queen Buff-tailed Bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) foraging on white clover.

Meet the Bumblebees

The low hum of bumblebees droning from flower to flower is one of the quintessential sounds of a British summer. The bees themselves are iconic, furry-bodied flying barrels. As well as helping produce the third of our food that is reliant on insect pollination, bumblebees have featured on postage stamps, given their names to film and TV characters, and even inspired a comic-book superhero.

Our familiarity with them is only skin-deep, however. The vast majority of the facts attributed to bumblebees (that they dance, sting once and then die, swarm, or make honey) are actually true almost entirely of their thinner, balder domesticated relatives, the honeybees. The most famous myth of all that bumblebees shouldnt be able to fly is best disproved by watching one buzz busily between flowers. Theyre not graceful to bumble means to move awkwardly or ineptly but theyre definitely airborne, even when carrying half their own weight in pollen.

Most insects are seen as small, creeping or scuttling things, pests in the garden and a nuisance everywhere else. Bumblebees are different. With their bulky, furry bodies, low droning sound and habit of visiting flowers, bumblebees are some of Britains favourite insects. The decline of bees in general is one of the most feared environmental problems and in the UK bumblebees even have an entire organisation the Bumblebee Conservation Trust, with 10,000 members devoted to monitoring and conserving them.

Bumblebees can remain active even at low temperatures.

It comes as a surprise to many people that theres more than one species of bumblebee, but in fact there are around 250 species worldwide. Twenty-seven have at some point called Britain home, although nationwide extinctions have now left us with just 24 species. Worldwide, bumblebees are generally insects of temperate regions, and some species can be found well inside the Arctic Circle. A few species do occur in the tropics, but most of those live in the cooler climate of the mountains.

Early Bumblebee (B. pratorum) in a garden.

Because of their historical popularity with people, bumblebees have been given multiple common names. Only six species have just one known common name, and there are a total of 49 English names for the 27 British species. Even the group name has changed over time bumblebee was first recorded in 1530, 80 years after humblebee was first given as a name for the group. In fact, humblebee was more common for centuries (Shakespeare and Darwin both mentioned humblebees), and the term only died out in the first half of the 20th century.

The genus name, Bombus, comes from the Latin for a loud buzzing, booming noise, while Psithyrus, the subgenus containing the quieter cuckoo bumblebees, means whispering. Some species names show their close association with the land: Bombus terrestris, of the earth, for the hole-nesting Buff-tailed Bumblebee; while B. pascuorum and B. pratorum are of the pasture and of the meadows, respectively.

Wanna- bees

Brightly coloured and distinctively patterned, bumblebees stand out from their background. Armed with a venomous sting, they use warning colouration rather than camouflage to avoid predation, trusting that most of their natural enemies have learned that striped black and yellow spells danger. The fewer patterns that a predator has to learn, the better for prey which is why so many bumblebees look very similar to each other.

Bee Chafer Trichius fasciatus, a beetle which mimics bumblebees.

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then bumblebees fan club extends well beyond humankind. Several other insects, including hoverflies, bee flies and the Maid of Kent rove beetle (Emus hirtus), are good mimics of bumblebees, copying their fur, their colouration and even their flight patterns. Some mimics, such as the hoverflies Merodon equestris and Volucella bombylans, even have several colour forms to mimic different species of bumblebee.

All this mimicry is done for a reason. Its a hard life being an insect, with so many bigger things keen to eat you, and a bumblebees sting is one of the few effective weapons against these threats. If a mimic can make a predator think even for a millisecond that it needs to be a bit careful when attacking, this gives the prey extra time to get away.