BLOOMSBURY WILDLIFE

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK

This electronic edition published in 2019 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY WILDLIFE and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in the United Kingdom, 2019

Copyright Amy-Jane Beer, 2019

Copyright 2019 photographs and illustrations as credited

Amy-Jane Beer has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this work

For legal purposes the constitute an extension of this copyright page

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third-party websites referred to or in this book. All internet addresses given in this book were correct at the time of going to press. The author and publisher regret any inconvenience caused if addresses have changed or sites have ceased to exist, but can accept no responsibility for any such changes

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication data has been applied for.

ISBN: 978-1-4729-5593-7 (PB)

ISBN: 978-1-4729-5594-4 (eBook)

ISBN: 978-1-4729-5595-1 (ePDF)

Design by Susan McIntyre

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletters.

For all items sold, Bloomsbury Publishing will donate a minimum of 2% of the publishers receipts from sales of licensed titles to RSPB Sales Ltd, the trading subsidiary of the RSPB. Subsequent sellers of this book are not commercial participators for the purpose of Part II of the Charities Act 1992.

Contents

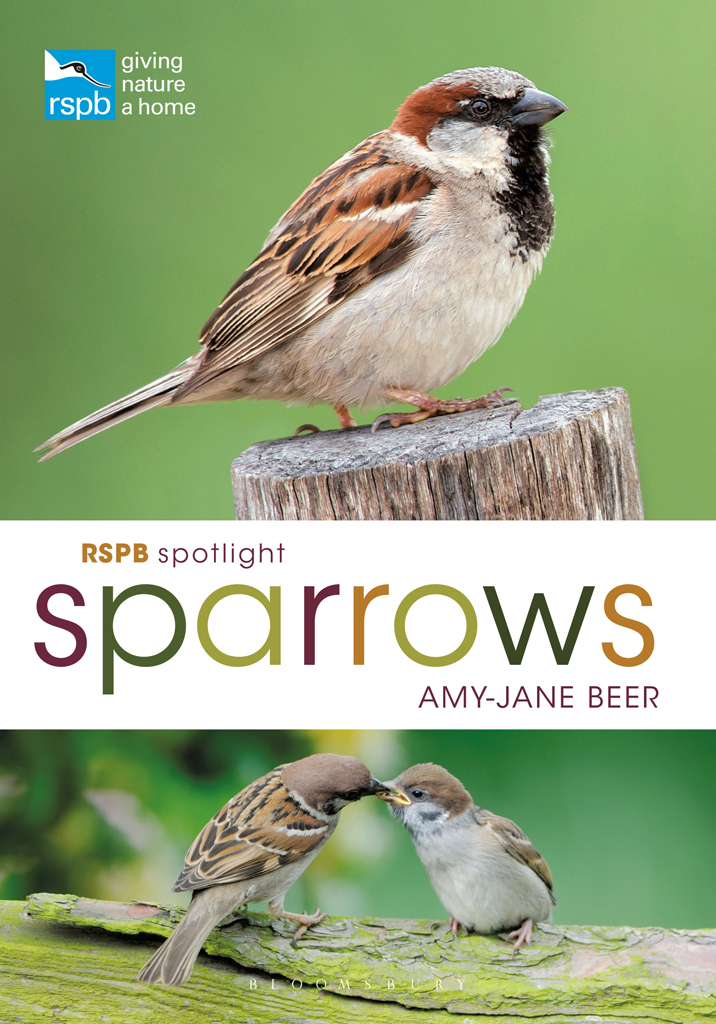

Meet the Sparrows

A torrent of chirping chatter issuing from a dense hedge is an unmistakable sign of sparrows living close to human settlements, cheekily at ease with artificial structures and facilities. But draw too near and they fall briefly silent before erupting from the vegetation in a blur of whirring wings, up and away towards another favoured hangout where they can resume their rowdy conversation unobserved. So, who are these skittish but irrepressible little scrappers?

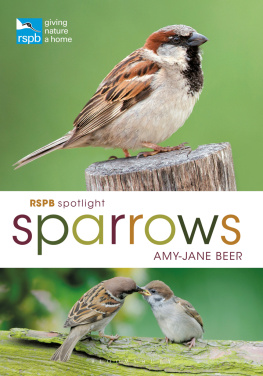

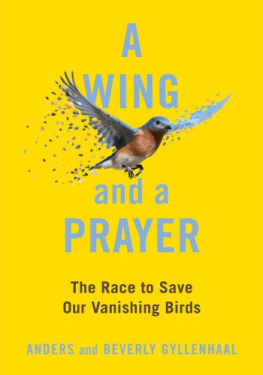

House Sparrows are closely associated with people and, in some places, are happy and willing to engage with humans.

A close association

Like mice, sparrows are human commensals species typically found in association with people, but on their terms, rather than ours. Its not that sparrows have any fondness for humans (in fact, they have good reason not to), but our settled landscapes, populated not only by people but also by abundant livestock, suit them. In taming wild places by cultivating and rearing domestic animals, and building houses, sheds, barns and storehouses, we have inadvertently created perfect habitats for these little opportunists, and contributed to their extraordinary success. Indeed, such is their reliance on human environments that, in huge parts of their range, sparrows cannot live without us.

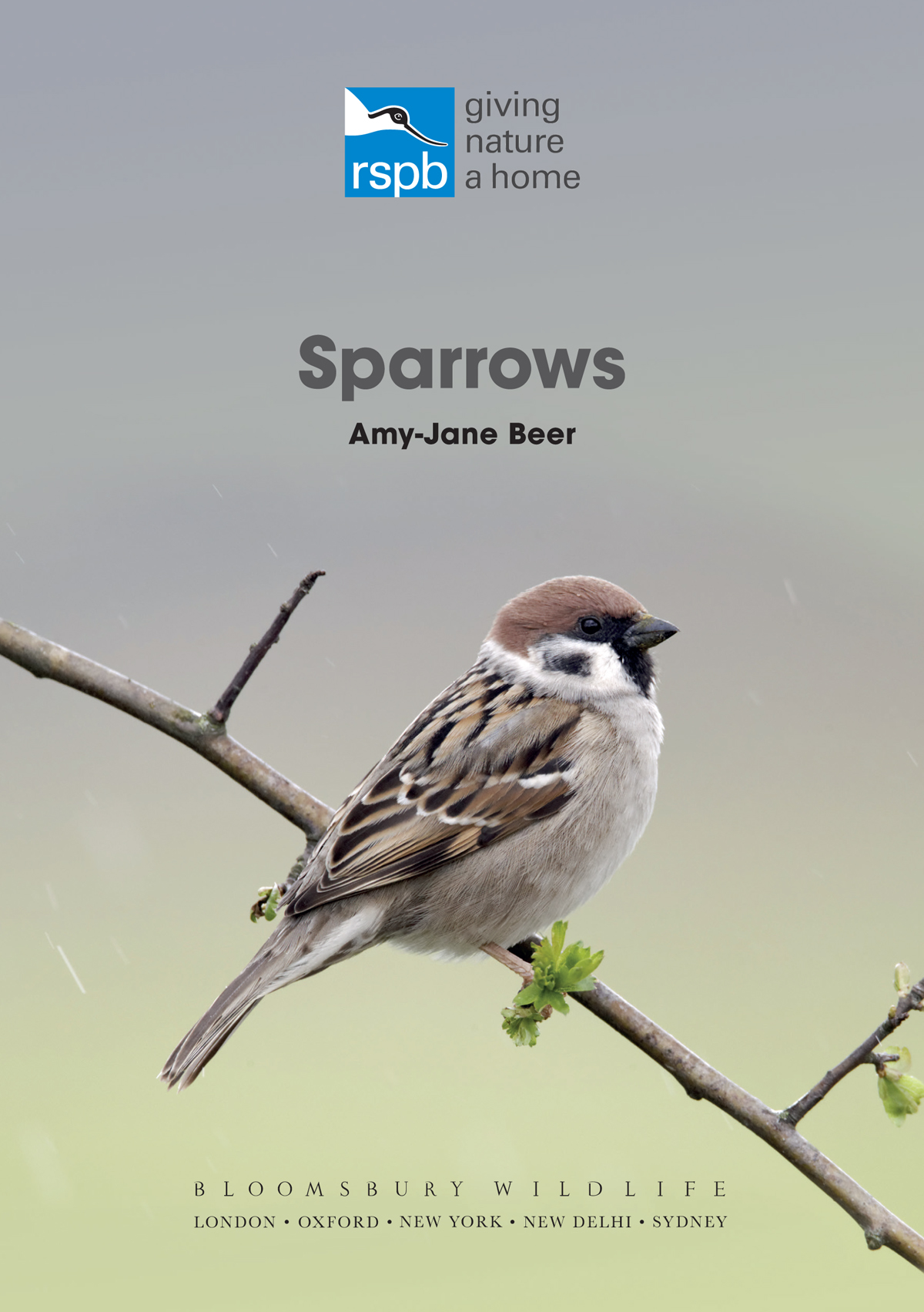

Tree Sparrows are smart-looking, sociable birds, with all members of a flock, male and female, looking and sounding much the same.

Seen clearly, House Sparrows are far more splendid than the rather dismissive label little brown job suggests. The plumage patterns are most striking in spring.

The cosmopolitan House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) is probably the most familiar bird on the planet after the domestic chicken, and is regarded with a peculiar mixture of affection and animosity. The abundance of this particular species has prompted a significant body of research, but the familiarity of sparrows as a group has earned them a sort of invisibility. For most of recorded history, they have been so common that they scarcely warranted attention beyond largely unsuccessful attempts to exterminate those that took too many liberties with our jealously guarded crops. Indeed, these archetypal little brown jobs (as birders like to call the plethora of occasionally hard-to-distinguish species in the order Passeriformes) were so numerous as to be scorned even by naturalists. In his 1896 Dictionary of Birds, Cambridge ornithologist Alfred Newton dismissed the House Sparrow as far too well known to need any description of its appearance or habits. However, in Britain at least, perceptions of sparrows have begun to change. When their numbers decreased suddenly and dramatically towards the end of the 20th century, we started to miss them, and to wonder what on earth was going on. Twenty years later, we still dont fully understand the decline, but we are finding new respect and fondness for our two native sparrow species.

The birds next door

The common name sparrow comes from the Old English speerwa, which in turn originates in the Aryan verb spar, to flutter, and perfectly encapsulates the restless movement of a flock all agitation and energy. The name sparrow has been applied to a wide variety of birds, not all of which are closely related, and many of which have since been reclassified, for example as buntings, finches and American sparrows. The species in this book are true sparrows, of the genus Passer. They belong in the family Passeridae, or Old World sparrows, although the range of some now extends into the Americas, Australasia and Micronesia.

In his first attempt at a systematic classification of living things in 1758, the taxonomist Carl Linnaeus named the House Sparrow Fringilla domestica, and grouped it alongside common seed-eating finches such as the Chaffinch (F. coelebs) and Brambling (F. montifringilla). This error was corrected two years later by French zoologist Mathurin Jacques Brisson, who established a new genus and named it Passer, the Latin word for sparrow, which was probably applied to a wide range of little brown birds in Roman times.

Passer is a name that hints at familiarity, and this is the type genus (the archetypal form on which other classifications are based) not only of the family Passeridae, but also of the vast bird order Passeriformes, otherwise known as the perching birds, which includes more than half of all bird species. A heavy burden of representative responsibility rests on those mundanely plumaged shoulders.