Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook. Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions. CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox. For Sam and Grey, with love

Bluebirds, among the most beloved of common species, could be the symbol of the modern bird crisis. Their populations plummeted through much of the last century. Today, the health of bluebirds, like this Eastern Bluebird, rests on the willingness of people to help them along. The North American Bluebird Society and local chapters are leading efforts to build nest boxes to provide homes for the birds throughout the continent.

INTRODUCTION

WHAT THE BIRDS ARE TELLING US

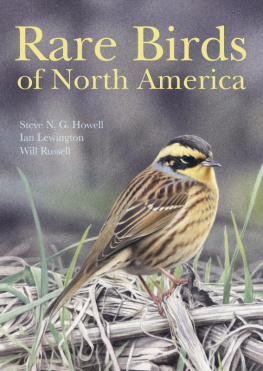

There he is, someone shouts, and sure enough the tiny sharp beak of Florida Grasshopper Sparrow No. 2050176 pokes out from behind a clump of wiregrass. Ever so slowly, the bird steps forward until he reaches the ledge of the giant mobile cage where he spent the past day getting ready for the mission ahead. Hatched in captivity and raised for this very moment, the bird woke up to something hes never seen before: The enclosures front metal wall is gone and an ocean of Central Florida grassland is spread out before him.

A handful of researchers watch crouched in the surrounding field, barely breathing as they wait to see if twenty years of research and experimentation will pay off. A full minute, then another tick by while the small brown bird, its spindly pink legs ringed with ID bands, just stands there. At last the sparrow makes his move. He half flies, half dives off the ledge into the wild in what everyone hopes will be the first step in rebuilding the continents most endangered bird.

At the other end of the country, a foot-and-a-half-tall California Spotted Owl is planted on her nest on a jagged, broken branch in the most remote corner of the Sierra Nevada mountain range. This is rugged country, filled with six varieties of towering pines and canyons carved out by a half dozen rivers, punctuated by giant boulders left scattered by glaciers four million years ago. The closest roads, more like dirt paths, get almost no traffic. The only sounds many days are chattering jays and juncos and the wind whooshing by at 6,000 feet above sea level.

There arent any people around, but the owl isnt exactly alone. Her every move is captured three different ways. When the owl launches into her loud, barklike call, the hoots are picked up by high-tech recorders strapped to nearby trees. When she shoots down to snag a flying squirrel, the hunt is captured by a motion-activated camera. When the owl leaves the nest to patrol her territory, a tiny transmitter attached to her tail feathers comes along. Every hoot, whistle, and call is tracked and analyzed in the worlds largest project using sound to study wildlife. In a few months, when researchers collect what amounts to a million hours of recordings from throughout the entire range, they hope to know what it will take to save this owl.

These two projects serve as bookends of the extraordinary work under way to protect birds across the hemisphere. The Grasshopper Sparrow is among the least-known and latest to brush up against extinction, while the Spotted Owl is among the best-known and part of the most storied chapter in the history of birds in the United States. Between them lies an array of rescue missionssome well financed, others threadbare, some succeeding, others losing groundthat will help determine the future of North Americas birdscape.

Birds are the most visible branch of wildlife, found in every corner of the globe and all too easy to take for granted. We certainly did during our first decade as birders, content to see them as gifts of nature here for our delight. But a series of advances in the science and technology of bird research recently led to a startling discovery. In the past fifty years nearly a third of the bird population in North America has withered away, up against the loss of habitat, shifting climate, and growing hazards of an urban world.

That translates to three billion birds of all sizes and shapes, in losses stretching from coast to coast, from the Arctic to Antarctica, through forests and grasslands, ranches and farms. As one veteran biologist, John Doresky with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Georgia, told us, Were in the emergency room now.

This is the story of the ranks of biologists, ranchers, ecologists, birders, hunters, wildlife officers, and philanthropists trying to protect the continents birds from a growing list of lethal threats and pressures. Theyve created transmitters the size of hearing aids that ride along with migrating birds and relay data back to earth via satellites and cell towers. Theyre building man-made nests to provide homes for stranded birds and moving entire populations to safer territories. Theyve borrowed advances from human genome research to study birds at a molecular level. Theyve discovered how to record bird songs and use artificial intelligence to analyze whats undermining them. Tactics range from community campaigns constructing thousands of tiny wooden houses for bluebirds (the bird at the top of this chapter as well as on the cover) to long-shot ventures like a $10-million-a-year experiment to save Hawaiis forest birds by neutering deadly mosquitoes.

In addition to scientists, some small private landowners, large corporations, cattle ranchers, and even the U.S. military are embracing new conservation ideas. The lineup includes elements right out of a futuristic fantasy: One nonprofit has landed a multimillion-dollar donation to fund what it calls de-extinction that uses cloning to try to bring long-vanquished birds back to life. Whether or not experiments like these succeed, they are already showing specialists how to peer into the genetic interiors of these ancient creatures to try reengineering their genes for the modern world.

Todays birds face a mix of peril and opportunity. The population losses have raised alarms and added urgencyeven desperationto the search for solutions. Scientists hope the stunning loss of billions of breeding birds in North America in the past five decades will be enough to ignite public and political support thats never been easy to build. The nonprofits, research centers, government agencies, and bird groups that have a history of mistrust and competition are recognizing the need to put away their differences and cooperate. This is a crisis. Were truly running out of time. There can be no tolerance for not working together, says Nadine Lamberski, the chief conservation officer at the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance, a leading research center.

Birds arent alone in facing threats, of course. Deteriorating ecosystems are affecting all manner of wildlife, fish, insects, and plants. Almost no bird species has been spared, from the most delicate jeweled hummingbirds to scrappy black crows, from a rainbow of warblers to such common species as blackbirds, owls, and sparrows. The loss of birds goes hand in hand with the disappearance of the monarch butterfly as well as bees, insects, and other animals crucial to the balance of nature. But people have always had a deep emotional connection with birdsand their woes help us see the broader loss of biodiversity. The story of birds may be the best way to witness close upeven in our neighborhoods and backyardsthe results of a natural system badly out of whack.

Birds provide a list of services that benefit people. They are among the environments workhorses, pollinating all manner of plant life and acting as natures farmers in spreading seeds and fertilizing the land. Birds consume an estimated 400 to 500 million tons of bugs a yeara mind-boggling sum when you consider that typical insects weigh just a milligram or two. They help keep water clean, refresh coral reefs, and maintain the population balances of rodents, worms, and snails. Researchers have discovered that watching birds even relieves stress and improves our mental health.

Next page