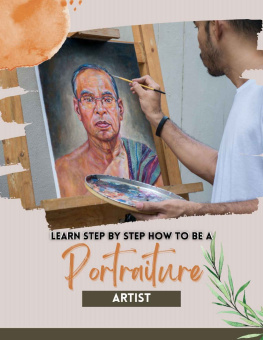

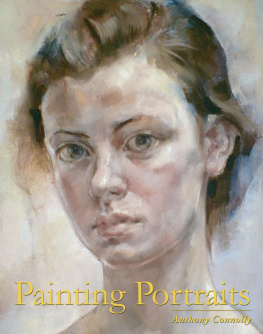

ON SIGHT-SIZE PORTRAITURE

2ND EDITION REVISED AND EXPANDED

Nicholas Beer

THE CROWOOD PRESS

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

In using the sight-size method, the artist stands back from the easel so that the drawing or painting appears the same size as the subject when viewed together from a specific distance. In this way, shapes and proportion, values and modelling can be checked definitively to scale alongside nature. Yet sight-size is more than a measuring device; it ultimately contributes to a way of seeing whereby the effect of the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. First documented by Roger de Piles in 1708, sight-size is primarily a portrait practice, but it is also effective in training the eye and therefore fundamental in an educational context.

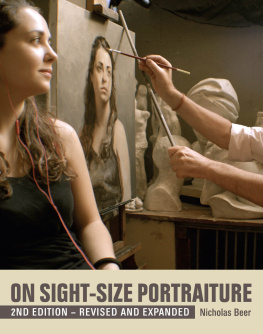

The authors studio in Salisbury.

There are other ways to fashion a portrait, but for many the effect of real light on a real object in real space is the catalyst to creativity. Working from nature opens to the artist a potential for spontaneity and change that cannot exist for those who are dependent on photographic or digital imagery. Painting and drawing from the sitter is the best way to imbue a portrait with psychology and life.

This book contains a wealth of information, but there is no substitute for studying at an atelier properly equipped with natural light, and space enough for students to review their work at the correct distance. Atelier training originates in the bottega system of the Renaissance, whereby novices were apprenticed to a master artist or craftsman who was responsible for their instruction. Thus Leonardo da Vinci was taught by Verrocchio; Michelangelo by Ghirlandaio; and Titian by Bellini.

Although it has antecedents in the methods of such seventeenth-century masters as Velzquez and Van Dyck, the use of sight-size (although not so-termed at the time) as a portrait practice was consolidated by painters of the British School during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries: first Reynolds, Gainsborough and Romney, then Stuart, Raeburn and Lawrence. The American John Singer Sargent was the last great practitioner of the method.

By the nineteenth century, Paris had become the artistic capital of Europe and the French Academy was a magnet for aspiring artists worldwide. Portraiture, however, was not ranked highly in the academic curriculum, and many students augmented their studies in the private ateliers of established painters like Thomas Couture, Lon Bonnat and Carolus-Duran.

I received my training at the Charles H. Cecil Studios in Florence, Italy. Cecil studied with R. H. Ives Gammell in Boston, who was taught by William Paxton. Before Paxton enrolled at the atelier of Jean-Lon Grme in Paris, he had worked with Dennis Miller Bunker, friend and associate of John Singer Sargent. In his revival of atelier training after the Second World War, Gammell advocated sight-size not only for figure drawing on an under life-size scale as a method of training the eye, but also cast drawing on the scale of life which leads directly to portraiture.

THE SIGHT-SIZE METHOD

1. Standing back from the easel to view the picture and the subject together at the same distance.

2. Walking forward to draw.

3. Drawing at the easel.

4. Drawing and sitter side by side.

In using the sight-size method, the artist stands back from the easel to view the picture and the subject together at the same distance, under the same light, and to the same scale.

At a basic level, sight-size is a measuring device effective in training the eye. With experience it contributes to a philosophy of seeing, whereby the overall effect is greater than the sum of the parts.

Working with the image alongside the subject is the only way to make definitive point-for-point comparisons on the scale of life that are otherwise impossible.

When standing back, the artist is able to consider shape, value and colour in a rightness of relation that is determined by, and which contributes to, the effect of the whole.

Seeing at a distance facilitates a capacity for significant selection, whereby the artist chooses what to emphasize and where to edit.

PART I

THE SIGHT-SIZE PORTRAIT TRADITION

Sight-size is first and foremost a portrait practice. It was not taught formally in the academies but passed from master to pupil in the private ateliers of portrait painters. The method has antecedents in terms of distance, scale, and unity of effect that were noted in the earliest treatises on painting and perspective.

Origins and Precedents

In Della Pittura of 1436, Leon Battista Alberti states that in order to evaluate the effect of a painting as a whole, the artist should view the work at a distance. He postulates that if a picture be conceived as a vertical plane that intersects the field of vision, then there is an optimal position from which it should be viewed: Each painter, endowed with his natural instinct, demonstrates this when, in painting this plane, he places himself at a distance from which point he understands the thing painted is best seen. As an aid to drawing, Alberti placed a stretched transparent veil (the vertical plane) in front of the subject. Working from a fixed point, he then traced the outlines of the object onto the veil under life-size but to scale. Albrecht Drer published a well-known series of engravings illustrating this method in his Unterweysung der Messung of 1525.

Leonardo da Vinci notes in his Tratatto della Pittura: It is also advisable to go some distance away, because then the work appears smaller, and more of it is taken in at a glance, and lack of harmony and proportion in the various parts and in the colours of the objects is more readily seen. (In practice this should be considered an absolute minimum distance.) In order to study perspective, Leonardo like Alberti recommended tracing the contours of objects on a transparent surface, in this case a piece of glass. It is significant that these observations on distance were made by Italian painters familiar with large-scale fresco decoration. In Northern Europe artists usually painted on a small scale while sitting at the easel: they did not have the same incentive to stand back.

In his Lives of the Artists (Le vite delle pi eccellenti pittori, scultori, ed architettori), at the beginning of the chapter on Titian, Vasari draws attention to the fact that Giorgione painted directly from life and that he was one of the first to do so: Despite his development of a fine style, however, Giorgione still used to work by setting himself in front of living and natural objects and reproducing them with colours applied in patches of harsh or soft tints according to life; he did not use any initial drawings, since he firmly believed that to paint directly with colours, without reference to drawing, was the truest and best method of working and the true art of design.

Next page