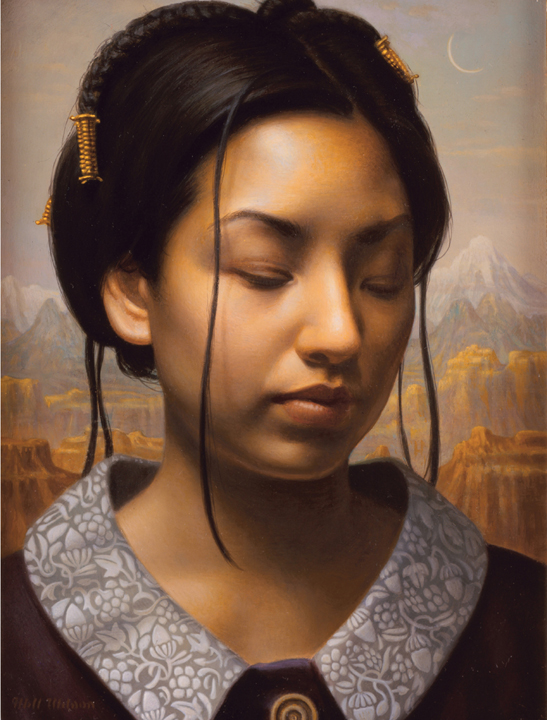

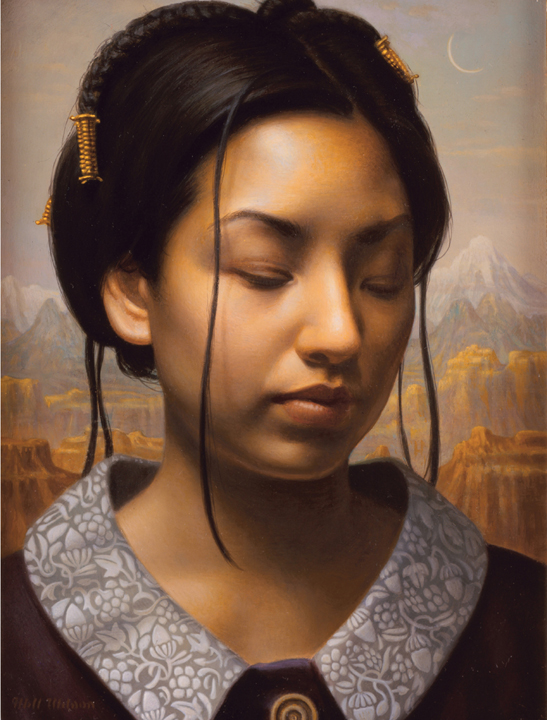

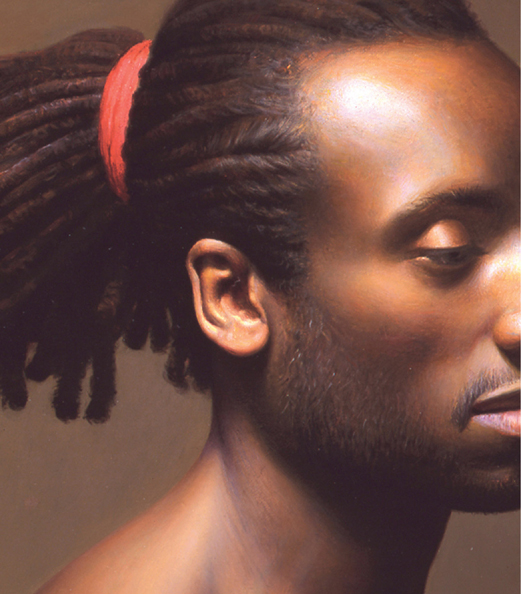

: Will Wilson, Fancy, 2000, oil on linen, 8 6 inches (22.2 17.1 cm)

Copyright 2010 by Suzanne Brooker

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Watson-Guptill Publications, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.watsonguptill.com

WATSON-GUPTILL is a registered trademark and the WG and Horse designs are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Brooker, Suzanne.

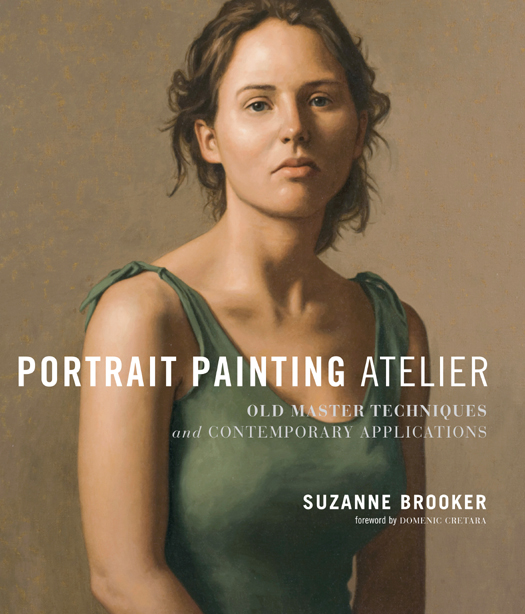

Portrait painting atelier : old master techniques and contemporary applications / Suzanne Brooker.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-8230-0835-3

1. Portrait painting--Technique. I. Title. II. Title: Old master techniques and contemporary applications.

ND1302.B76 2010

751.4542--dc22

2009009647

v3.1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book was made possible by the generous support of friends, family, students, and colleagues, with special thanks to James Maloney. To Ron Dalton, for his patience as my photographer. Many thanks are also due to the Gage Academy of Art, whose encouragement in my role as an instructor over the last decade is greatly appreciated. To all the artists who so graciously donated their paintings to this book project, thank you. And most of all, to all my teachers, who inspired me with your own books and patient teaching, your insight and guidance should appear on these pages.

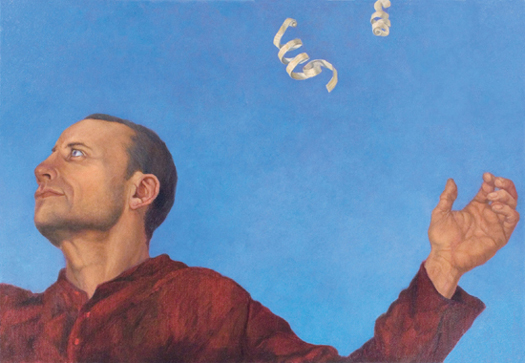

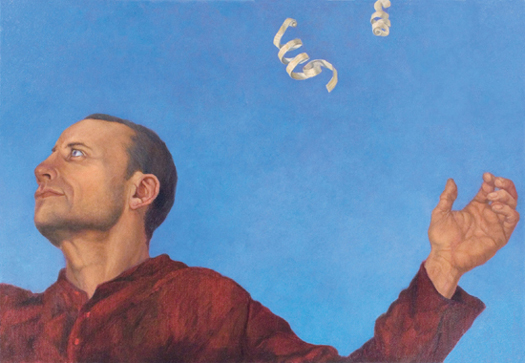

Suzanne Brooker , Portraits of Men, Metaphors of Wood: Revelation, 2003, oil on canvas, 22 32 inches (55.9 81.3 cm)

A portrait can take on the quality of a metaphor when it is combined with an object on a field of abstracted space. The gesture of the model is further heightened by its cropping and placement within the canvas, creating a dynamic tension between the model and the background.

To students who strive with passion and persistence to master the art of painting

CONTENTS

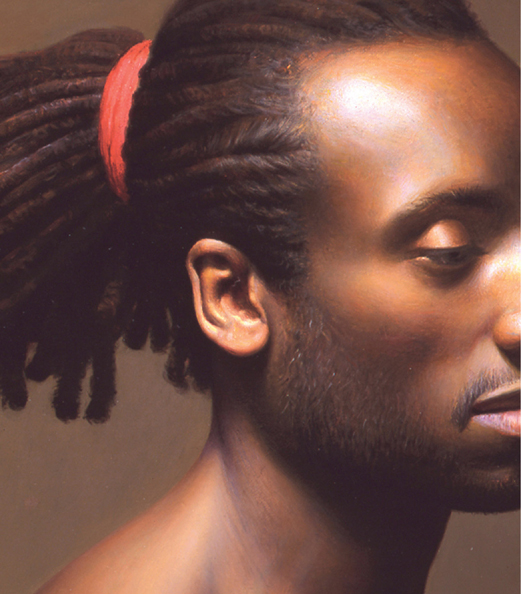

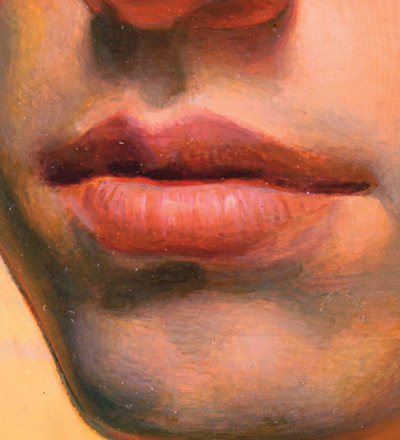

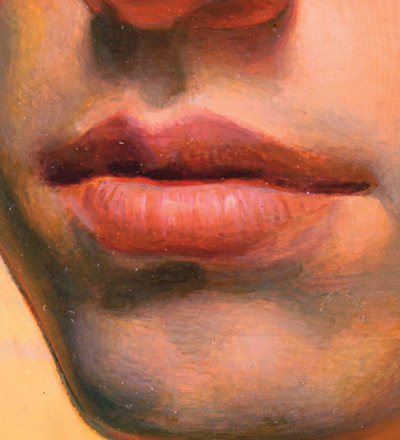

Details of Will Wilsons paintings (from left to right): Roy, Pablo, and Valencia. The full images can be seen on , respectively.

FOREWORD

byDOMENIC CRETARA

Although I have been continuously involved with art since childhood, I date the beginning of my career as a painter to when I graduated from the Art Department of Boston University in 1970. When I first entered school I had no intention of becoming an academic, but a few months into the program I discovered that I was an acute observer of my own education and that my visual perceptions and studio habits were being subtly but inexorably modified by my courses of study. I caught a glimpse of some overall plan. Furthermore, every member of the facultydespite having diverse opinions, teaching methods, and stylistic preferenceswere all somehow acting in concert to realize that plan.

The overall strategy consisted of an approach to form based on looking at nature. This may seem at first deceptively simple; but when looking is carried out with a pencil or a brush in hand it becomes close observation. So what might be called a rational way of seeing is still completely perceptual. This method is enhanced by informing what one sees with centuries-old traditions that exist within Western art and culture. One could say that seeing is a continuous process where the ideas create the perceptions but the perceptions in turn alter the ideas: First you draw what you see, then you draw what you know, and finally you know what you see.

One of the implications of this idea is that, while art may remain mysterious in its essence, painting and drawing are rational activities and therefore teachable. There is something intellectually and emotionally satisfying about clearing away the sickly miasma of subjectivity that is generally assumed as the artists way of thinking and feeling. What an experience! The ultimate goal may be indescribable, but the means for getting there, though difficult to master, are clear and demonstrable. This vision has guided me through nearly forty years of painting, exhibiting, and teaching. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that one of my former students, Ms. Suzanne Brooker, has taken up this mission of teaching not as a mere passive imparting of formulas but as an approach to lifea revealing explication of what it means to think like a painter.

So often I hear artists who are also professors of painting and drawing evaluate student work by saying, Theyve got great skills, but its too bad they cant think. It is as if visual ideas preexisted in the mind, and skills were simply the means by which to make them visible. As soon as the apparently plausible notion that skills and ideas are separate entities is conceded, the argument is lost and skills are relegated to an inferior, merely manual status. However, if skills and ideas are one and the same, why do we persist in separating them, and what measures can we take to correct this fallacy? Suzanne Brookers book, Portrait Painting Atelier, provides a long overdue solution to this problem.

Domenic Cretara , Italian Sketchbook Page (from Ritrovamento de la Croce by Il Poppi) 2006, graphite pencil on paper, 7 10 inches (19.7 27.3 cm)

Creating study drawings from Old Master paintings brings fresh insight on compositional design, color palettes, paint handling, and a models gesture. A sketchbook can become a powerful tool that documents a painters observations.

Painters think with their eyes and hands as well as with their pigments, brushes, and palettes. Just as we walk with our whole body, and not just with our feet, painters brains process the world through their bodies and their materials. Doing is thinking. By making the reader sensitive to the subtlest behaviors of pigments and media, by explaining how the artist can take something as immaterial and private as ones own optical sensations and create an objective (and objectively verifiable) equivalent of those sensations on canvas, Ms. Brooker seamlessly connects thinking with craftsmanship. For example, when the author describes the construction of the root of the nose, she isnt giving a formula for how to draw that anatomical detail. Instead, she invites the reader/artist to notice that particular form and to see how it is connected to the other forms of the head. She gently guides the readers attention by describing and having them perform specific tasks in a sequence of operations, which when done with care will lead to critical understanding. This understanding provides insight into how the generalized notions of the human head and face that we have acquired in our minds are related to and corrected by specific instances of those forms as we see them and think about them when we draw and paint.