A Oneworld Book

First published in North America, Great Britain

and Australia by Oneworld Publications, 2016

This ebook published by Oneworld Publications, 2016

Copyright Anna Beer 2016

The moral right of Anna Beer to be identified as the Author

of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78074-856-6

eISBN 978-1-78074-857-3

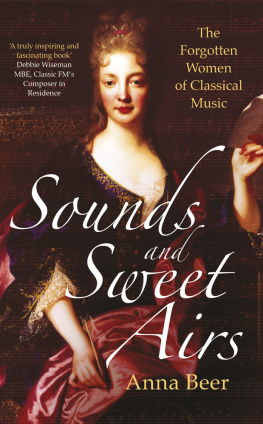

Cover illustration lisabeth Jacquet de La Guerre (c. 1704) by Franois de Troy.

Our sincere thanks to the owner of the portrait for allowing its reproduction.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders for the use

of material in this book. The publisher apologizes for any errors or omissions

herein and would be grateful if they were notified of any corrections that

should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

Typeset by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London WC1B 3SR

England

For Roger

A chantar mer de so quien non volria

I must sing about it, whether I want to or not.

La Comtessa del Dia, c. 1175

Contents

List of Illustrations

Francesca Caccini

Title page of Il Primo Libro delle Musiche 1618 (Wikimedia Commons)

Barbara Strozzi

Portrait by Bernardo Strozzi, c. 163040 (Gemaeldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden; Bridgeman Images)

lisabeth Jacquet de la Guerre

Portrait by Franois de Troy (private collection)

Marianna Martines

Portrait by Anton von Maron (DEA/A. DAGLI ORI; Getty Images)

Fanny Hensel

Portrait by Wilhelm Hensel ( Pictorial Press Ltd; Alamy)

Clara Schumann

Portrait Clara Wieck im ihrem 21. Lebensjahr by Johann H. Schramm, 1840 (Robert-Schumann-Haus Zwickau)

Lili Boulanger

Photograph, 1913 (Bibliothque Nationale de France)

Elizabeth Maconchy

Photograph, 1941 (Nicola LeFanu)

Venice, 1568

Maddalena Casulana, the first woman to publish her own music, challenges the foolish error of men who believe that they are the sole masters of the high intellectual gifts necessary for composition. She suggests that those gifts might be equally common among women.

The Convent of San Vito, Ferrara, 1594

A man hearing the nuns sing their sublime music is overwhelmed. He writes that the nuns are not human, bodily creatures, but were truly angelic spirits. He listens in a culture in which, whether heard as angels, sirens, saints or sorceresses, whether deemed super natural or un natural, womens exceptional ability goes against nature.

Berlin, 1850

Reviewers respond to the publication of works by Fanny Hensel, the elder sister of the celebrated composer Felix Mendelssohn. They are sure that, because she is a woman, the music lacks a commanding individual idea, an inner aspect, the powerful feeling drawn from deep conviction. They are sure that music will always betray the sex of its composer.

Notes from the silence

This book is a celebration of the achievements of a handful of women over four centuries of Western European history. Neither angels nor sorceresses, merely formidably talented human beings, these female composers demonstrate, again and again, their high intellectual gifts; they express, again and again, powerful feeling drawn from deep conviction. They created their music in societies that made certain places off-limits for a woman, from the opera house to the university, from the conductors podium to the music publisher societies where certain jobs, whether in cathedral, court or conservatoire, were ones for which they could not even apply.

But it is the cultures of belief within which they lived that made their task all the harder. From seventeenth-century Florence to twentieth-century London, women creating music triggered some profound and enduring fears. The Book of Samuel states that listening to a womans voice is sexual enticement, and that was enough to silence women, in church and synagogue, if not beyond. It is a fairly straightforward step from the Book of Samuel to the recommendation made by an early Christian Father that nuns should sing their prayers, but make no sound, so that their lips move, but the ears of others do not hear. These prohibitions upon womans expression may have taken less draconian forms as the years passed, but the fear underlying them, of the sexualized threat of the creative woman, remained. This is why each composer in this book composed her music in the shadow of the courtesan, her sexual life scrutinized, her virtue questioned, simply because of her trade.

Every female composer knew that her work would always be understood in terms of her sex, or, rather, what her society believed her sex was capable of achieving. When, in 1919, a violin sonata by British-born American Rebecca Clarke won an important prize, questions were asked. Had the work actually been submitted by the male composers Ernest Bloch or Maurice Ravel under a pseudonym? How could a woman have created such a formally rigorous yet powerful work? Rebecca Clarke could and did do just that in 1919, but her career was not to be sustained. Clarke was not the first, nor would she be the last, woman to give up composing, worn down by her societys ability to silence her, succumbing to her own self-doubts. Because women, just as much as men, believed the stories we tell ourselves about genius, so often an exclusive men-only club. Clara Wieck, soon to be married to (the tortured genius) Robert Schumann, wrote: I once thought that I possessed creative talent, but I have given up this idea; a woman must not desire to compose not one has been able to do it, and why should I expect to? The world-renowned teacher of composition, Nadia Boulanger, knew what she had to sacrifice in order to pursue her successful career in music: Artists think only of their art, and they consider it is totally incompatible with the joys of family life. From the day a woman wants to play her one true role that of mother and wife it is impossible for her to be an artist as well.

How to exorcize the ghost of Claras despair? How to challenge Nadias definition of the impossible? The pioneering efforts of feminist musicologists offer one response to Clara Schumann. These scholars were, and remain, determined to show that women were able to do it (the International Encyclopedia of Women Composers alone has more than six thousand entries) and it is both revelatory and humbling to read of the experiences of some of the early feminist researchers. Back in 1979, Professor Marcia Citron, seeking to find out more about Fanny Hensels music, first started work in the Mendelssohn Archiv at the Stattsbibliothek Preussischer Kulturbesitz (West Berlin). There was no library catalogue of Hensel holdings. Instead, the director Rudolf Elvers informed scholars as to what they were, or were not, allowed to see. Professor Citron battled on, often desperately copying out scores by hand in the justified fear that she would not be allowed to see the same manuscript again on her next visit. She was therefore surprised, in 1986, when the director, Rudolf Elvers, said that there had been no qualified musicologists interested in the Hensel manuscripts. He was, in his own words, waiting for the right man to come along, and, in the meantime, expressed his irritation with all these piano-playing girls who are just in love with Fanny. Elverss verdict on Hensel? She was nothing. She was just a wife.

Next page

![Willis - Beer: a cookbook: good food made better with beer: [recipes]](/uploads/posts/book/224368/thumbs/willis-beer-a-cookbook-good-food-made-better.jpg)