All spelling and orthography have been modernised, except for the occasional moment when the difficulties of understanding the original text are outweighed by the insight and pleasure to be gained from a direct encounter with the remarkable language of Raleghs own time. Readers who wish to enjoy the letters and other documents in their original form should turn to Sir Walter Ralegh in his own words , where works such as Youings and Lathams 1999 edition of the Letters are listed.

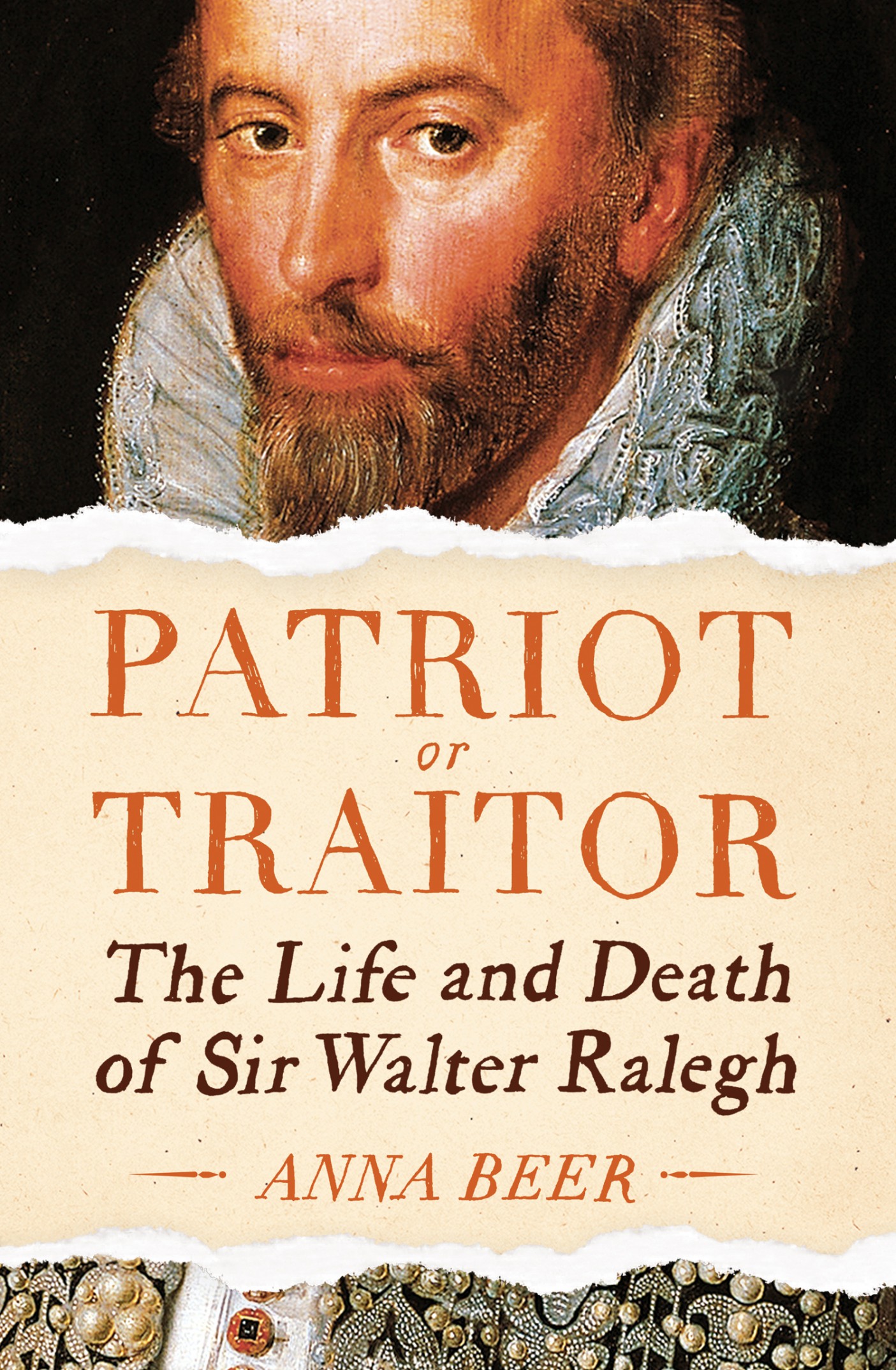

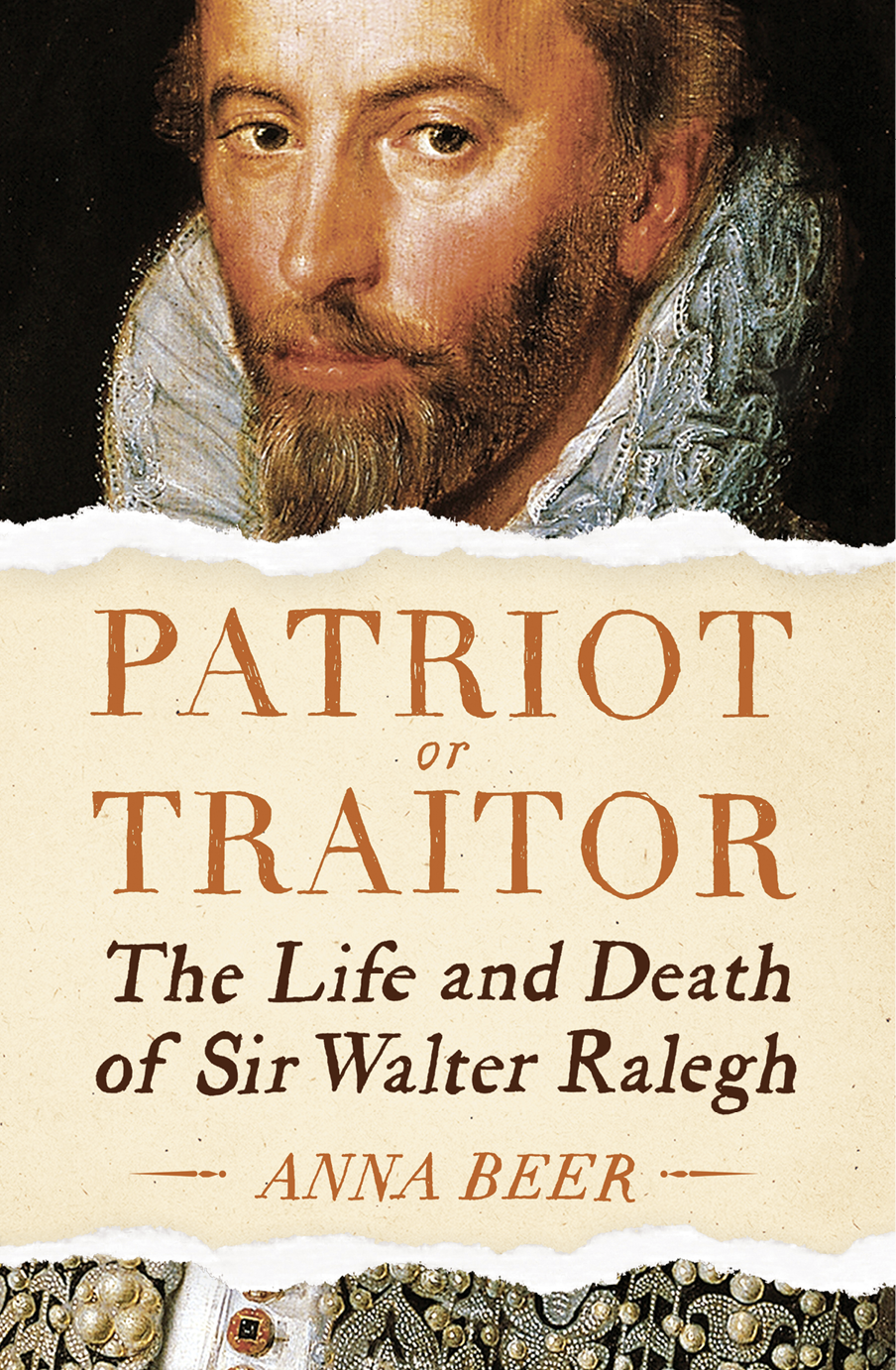

Sir Walters contemporaries wrote his surname as Raleigh, Raliegh, Ralegh, Raghley, Rawley, Rawly, Rawlie, Rawleigh, Raulighe, Raughlie and Rayly. This is hardly a surprise. A well-known playwright never signed his name Shakespeare, preferring (usually, but not always) Shakspere. I have chosen Ralegh because that, more often than not, was Sir Walters own spelling, and he used it consistently in later life.

As for how to pronounce Ralegh, I spent many years calling him Rawlee (the evidence being the punning attacks of his hostile contemporaries) but now prefer his name to rhyme with barley. We are slightly clearer about Raleghs own pronunciation of his first name: a deep, Devonian Water.

The scaffold: Winchester

A scaffold is being built beneath his window, twelve feet square and railed about. He knows what is coming, because he has been told.

Since you have been found guilty of these horrible treasons, the judgement of the court is that you shall be had from hence to the place whence you came, there to remain until the day of execution. And from thence you shall be drawn upon a hurdle through the open streets to the place of execution, there to be hanged and cut down alive, and your body shall be opened, your heart and bowels plucked out, and your privy members cut off, and thrown into the fire before your eyes; then your head to be stricken off from your body, and your body shall be divided into four quarters, to be disposed of at the kings pleasure.

And God have mercy on your soul.

He knows what is coming, because he has watched two other traitors, Catholic priests William Watson and William Clarke, being hung, drawn and quartered just days before. It was very bloodily handled for they were both cut down alive, tutted one spectator. Then again, for most, that was the whole point of the exercise to force the guilty to confront their own corruption through witnessing their own disembowelling and dismemberment. Despite the bloody handling both men die boldly, Clarke seeing himself as a martyr, Watson aggressively unrepentant and delighting in his treason or, as he saw it, his perfectly reasonable demand for religious toleration for his fellow Catholics. Their quarters are now set on Winchester gates and their heads on the first tower of the castle as a lesson to all, their traitors hearts already displayed on the scaffold, the public proof of their hidden treachery.

As the priests carcasses begin rotting, another traitor, George Brooke, is beheaded in the castle yard. Brooke is of the nobility, his brother a lord, so he avoids being hung, drawn and quartered; he will merely be decapitated. His is a better death than that of the priests, at least from the point of view of the authorities. Not bold; Brooke meets a patient and constant end, according to the Kings chief minister, Robert Cecil, who is taking notes. And yet, even at the last, Brooke only admits to errors not crimes, and at the holding up of the traitors head, when the executioner cries God save the King, he is not seconded by the voice of any one man but the sheriff. Is it revulsion or apathy on the part of the crowd? It is hard to tell. Few people come to watch, and only a couple of men of quality.

The Bishop of Winchester, who has prepared George Brooke well for his constant end, does his rounds of the remaining traitors, including Brookes older brother Henry, Lord Cobham, and Sir Walter Ralegh. The Bishop has instructions from King James to prepare them for their ends as likewise to bring them to liberal confessions and by that means reconcile the contradictions.

The Crown, troubled by the refusal of their two high-profile prisoners to admit their treason, is haunted by the contradictions in the testimonies of Ralegh and Cobham. King James desires not merely that justice be done, but that justice is seen to be done. The Bishop finds Ralegh well-settled and resolved to die a Christian and a good Protestant, which is all very well, but for the point of confession he found him so strait-laced that he would yield to no part of Cobhams accusation.

Dealing with Watson and Clarke had been straightforward in comparison. The priests had planned to launch a surprise attack on the royal court at Greenwich on Midsummers Night. The King would be kidnapped and then held hostage in the Tower of London, until he granted the prize of religious tolerance: a Utopian ideal for those, both Catholics and evangelical Protestants, whose beliefs took them beyond the bounds set by the Church of England. To that end, any royal ministers who stood in the way of toleration would be removed. In their more fanciful moments, the conspirators saw themselves in the ministers places. In their even more fanciful moments, they believed this could be achieved without violence. Ideally, the King himself would convert to Catholicism. Watson even looked forward to discussing the finer points of religion with the theologically minded James I.

.jpg)