Copyright 2005 by Tim Page

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce

selections from this book, write to:

Steerforth Press L.C., 25 Lebanon Street

Hanover, New Hampshire 03755

Frontispiece photograph of Robert Ingersoll appears courtesy robertingersoll.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ingersoll, Robert Green, 18331899.

Whats God got to do with it?: Robert G. Ingersoll on free thought, honest talk, and the separation of church and state / edited and with an introduction by Tim Page. 1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-58642-197-7

1. Agnosticism. 2. Free thought. 3. Church and states United States. I. Page, Tim, 1954- II. Title.

BL2720.A2I55 2005

211.7-dc22

2005010101

v3.1

While I am opposed to all orthodox creeds, I have a creed myself; and my creed is this. Happiness is the only good. The time to be happy is now. The place to be happy is here. The way to be happy is to make others so. This creed is somewhat short, but it is long enough for this life, strong enough for this world. If there is another world, when we get there we can make another creed. But this creed certainly will do for this life.

Robert Green Ingersoll, 1882

Contents

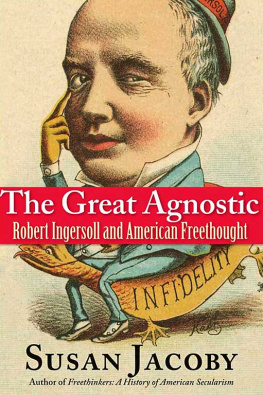

ROBERT INGERSOLL

He was an impassioned patriot, an early member of the Republican Party, and a supporter of Abraham Lincoln. He was a tireless advocate for justice and liberty, a man who thought the Declaration of Independence the bravest, grandest political document ever conceived. He spoke out on most of the great is sues of his day race relations, womens rights, birth control, capital punishment, the role of religion in a modern state with a combination of moral authority and mischievous wit. The power of his ideas and his skills as an orator made him one of the most famous men in America. And today in an era of faith-based initiatives and White House prayer breakfasts, at a time when televangelists attack childrens cartoon characters for supposed homosexual tendencies and evolution is downgraded to a mere theory, one out of many, in textbooks the wisdom of Colonel Robert Ingersoll (18331899) is as resonant and relevant as ever.

Ingersoll is one of the great lost totemic figures in American history, and it is time that he was brought back into our collective consciousness. After Ralph Waldo Emerson, he may have been the busiest and most controversial lecturer of the nineteenth century, attracting many thousands of listeners across the country over the course of each year. His works were published in twelve volumes; he has been the subject of half a dozen biographies; he was a hero to Frederick Douglass, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Thomas Edison (who recorded Ingersolls speaking voice on early wax cylinders). Oscar Wilde called him the most intelligent man in America. Mark Twain praised one of his speeches as the supreme combination of words that was ever put together since the world began, and added, Bob Ingersolls music will sing through my memory always as the divinest that ever enchanted my ears. And H. L. Mencken, writing in the 1920s, suggested that what this grand, gaudy, unapproachable country needs and lacks is an Ingersoll:

He drew immense crowds; he became eminent; he planted seeds of infidelity that still sprout in Harvard and Yale. Thousands abandoned their accustomed places of worship to listen to his appalling heresies, and great numbers of them never went back.

Appalling heresies. In these two words lies the secret of Ingersolls disappearance from view. Although he called himself an agnostic, he was usually labeled an atheist and except when he was exercising unusual tenderness with an audiences sensibilities he scarcely seemed to recognize the distinction. And Ingersoll was hardly the sort of quiet, respectful doubter who is still found in every city and town across the nation. Instead, he roared out his skepticism in sharp, lively, cadenced oratory on platforms from Maine to California. His speeches and articles carried aggressively provocative titles such as Some Mistakes of Moses and Why I Am an Agnostic.

Ingersoll was particularly opposed to any attempt to meld church and state, which he considered an erosion of the secular principles set down by the Founding Fathers. He knew that the omission of any reference to God in the United States Constitution was no mere oversight but the result of a consensus accepted and agreed to by even those among the framers who were deeply religious that it was dangerous, and unworkable, to incorporate any formal acknowledgment of the supernatural into this fledgling experiment in democracy:

Suppose, then, that we amend the Constitution and acknowledge the existence and supremacy of God what becomes of the supremacy of the people, and how is this amendment to be enforced? A constitution does not enforce itself. It must be carried out by appropriate legislation.

Will it be a crime to deny the existence of this constitutional God? Can the offender be proceeded against in the criminal courts? Can his lips be closed by the power of the state? Would not this be the inauguration of religious persecution?

Orthodox religionists despised Ingersoll, of course, all the more so as local infamy begat widespread fame. He was denounced from pulpits and editorial pages as a cynic, a rogue, as the Devil himself. His books were banned from libraries; his speeches were regularly disrupted. In 1881, the chief justice of the Delaware Supreme Court went so far as to threaten Ingersoll with indictment under local blasphemy laws (a threat that Ingersoll took seriously enough to cancel all further visits to the First State).

Despite it all, Ingersoll was an enormously popular attraction and made a handsome living from his tours. And with good reason even those who disagreed with him most strenuously often found themselves stimulated by the vigor of his arguments and charmed by his humor, which was both daring and self-deprecatory. As the Progressive Senator Robert M. (Fighting Bob) LaFollette recalled, He was witty; he was droll; he was eloquent; he was as full of sentiment as an old violin.

When Ingersoll died, when he was no longer around to proclaim his thoughts in person, much of his magic died as well. Moreover, he belongs to that not-inconsequential roster of artists and writers who never created a polished master piece. Rather, he returned to the same ideas again and again, in lecture after lecture, with the result that his collected works might qualify for inclusion in what the Firesign Theatre dubbed the Department of Redundancy Department. But he does not deserve his present obscurity: If Ingersoll is best sifted for nuggets rather than read straight through, the best of those nuggets remain potent and timely.

The ignorant are not satisfied with what can be demonstrated. Science is too slow for them, and so they invent creeds. They demand completeness. A sublime segment, a grand fragment, are of no value to them. They demand the complete circle the entire structure. (Ingersoll in 1877)

Some chips from a grand fragment, then: Robert Green Ingersoll was born on August 11, 1833, in Dresden, a tiny hamlet in the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York. (The birthplace has been preserved and restored by the Council for Secular Humanism, which runs it as a museum in the summer months.) The boy was the youngest of five children born to Mary Livingston Ingersoll and her husband, John, a Congregational minister. Although Ingersoll was only two years old when his mother died on December 26, 1835, he remembered the event vividly and wrote of it on several occasions. Nearly forty-eight years ago, under the snow, in the little town of Cazenovia, my poor mother was buried, begins one passage from 1883. I remember her as she looked in death. That sweet, cold face has kept my heart warm through all the changing years.