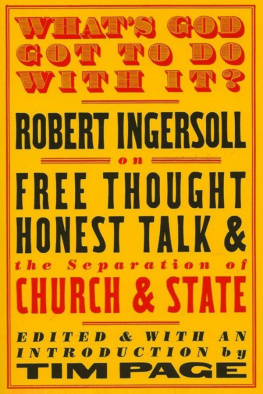

The Great Agnostic

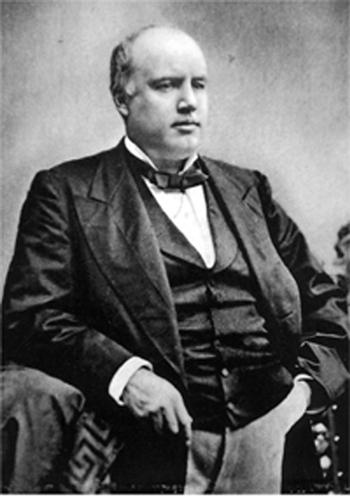

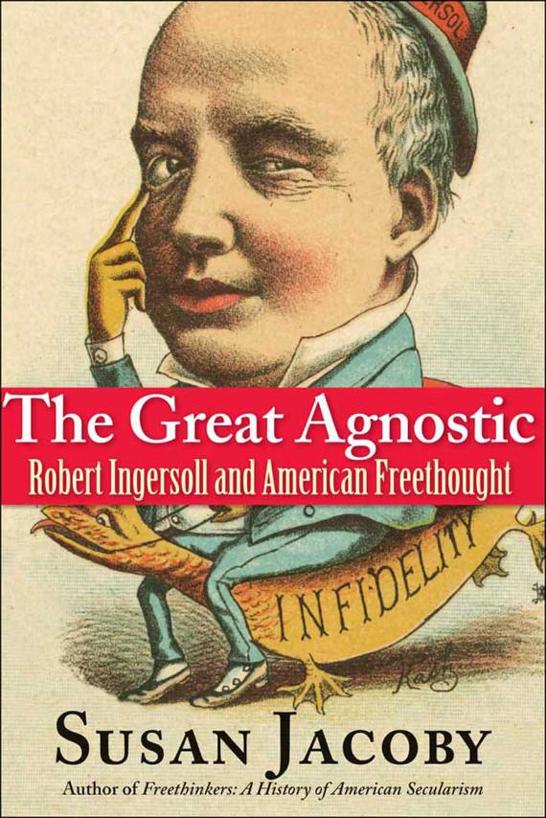

Robert Green Ingersoll, 1877

The

Great

Agnostic

Robert Ingersoll and

American Freethought

Susan Jacoby

Copyright 2013 by Susan Jacoby.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu (U.S. office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

Set in Janson type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jacoby, Susan, 1945

The great agnostic : Robert Ingersoll and American freethought / Susan Jacoby.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-13725-5 (clothbound : alk. paper)

1. Ingersoll, Robert Green, 18331899. 2. FreethinkersUnited StatesBiography. 3. FreethinkersUnited StatesHistory.

I. Title.

BL2790.I6J33 2013

211.7092dc23 2012027881

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of

ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In memory of Aaron Asher

The most formidable weapon against errors of every kind is reason.

THOMAS PAINE

Contents

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank my editor at Yale, Christopher Rogers, for taking on this project; James Johnson for designing the perfect, evocative cover; Joyce Ippolito for an outstanding job of copy editing, including her identification of several words I have been misspelling since childhood; and Laura Jones Dooley for her second look.

As always, I am grateful for the efforts of my longtime literary agents, Georges and Anne Borchardt.

Finally, I wish to thank Jay Barksdale and to say that this book was written in the Allen Room under the shadow of the lions at that great institution, the New York Public Library.

Introduction

How and why do some public figures who were famous in their own time become part of a nations historical memory, while others fade away or are confined to what is known on the Internet as niche fame? Robert Green Ingersoll (18331899), known in the last quarter of the nineteenth century as the Great Agnostic, once possessed real fame as one of the two most important champions of reason and secular government in American historythe other being Thomas Paine. Indeed, one of Ingersolls lasting accomplishments as the preeminent American orator of his era was the revival of Paine in the historical imagination of a nation that had been the beneficiary, throughout its revolutionary era, of some of the most memorable words ever written in the cause of liberty.

Ingersoll stepped onto the public stage as the leading figure in what historians of American secularism consider the golden age of freethoughtan era when immigration, industrialization, and science, especially Charles Darwins theory of evolution by means of natural selection, were challenging both religious orthodoxy and the supposedly simpler values of the nations rural Anglo-Saxon past. That things were never really so simple was the message Ingersoll repeatedly conveyed as he spoke before more of his countrymen than elected public leaders, including presidents, in an era when lectures were both a form of mass entertainment and a vital source of information. Traveling across the continent at a time when most Americans did not, he spread his message not only to urban audiences but to those who had ridden miles on horseback to hear him speak in towns set down on the prairies of the Middle West and the cattle-grazing lands of the Southwest. Between 1875 and his death in 1899, Ingersoll spoke in every state except Mississippi, North Carolina, and Oklahoma. Known as Robert Injuresoul to his clerical enemies, he raised the issue of what role religion ought to play in the public life of the American nation for the first time since the writing of the Constitution, when the founders deliberately left out any acknowledgment of a deity as the source of governmental power. Ingersoll said of the founders:

They knew that to put God in the Constitution was to put man out. They knew that the recognition of a Deity would be seized upon by fanatics and zealots as a pretext for destroying the liberty of thought. They knew the terrible history of the church too well to place in her keeping, or in the keeping of her God, the sacred rights of man. They intended that all should have the right to worship, or not to worship; that our laws should make no distinction on account of creed. They intended to found and frame a government for man, and for man alone. They wished to preserve the individuality of all; to prevent the few from governing the many, and the many from persecuting and destroying the few.

Of course, this view of the founders intentions is far from universally accepted in the United States today. It is unlikely that any American politician with national ambitions would dare describe the secular spirit and letter of the Constitution so forthrightly in the twenty-first century. They knew that to put God in the Constitution was to put man out. It is all too easy to envision this sentence in a thirty-second attack ad on a modern politician who openly advocates secular values, yet the undeniable absence of God from the Constitution poses a serious historical problem for pious originalists who, while insisting that the Ingersoll would have been even more astonished, given his generations faith in education and technology, at the same candidates dismissal of universal higher education as something that only a snob would support.

To the question that retains its politically divisive power todaywhether the United States was founded as a Christian nationIngersoll answered an emphatic no. The marvel of the framers, he argued, was that they established the first secular government that was ever To nineteenth-century freethinkers, as to their eighteenth-century predecessors, intellectual and material progress went hand-in-hand with abandonment of superstition, and strong ties between government and religion amounted to state-endorsed superstition. Born decades before cities were illuminated by electricity, before the role of bacteria in the transmission of disease was understood, before Darwins revolutionary insight that humans were descended from lower animals was fully accepted even within the scientific community, Ingersoll was the most outspoken and influential voice in a movement that was to forge a secular intellectual bridge into the twentieth century for many of his countrymen.

From a twenty-first-century perspective, it is clear that the golden age of freethought, which stretched roughly from 1875 until the beginning of the First World War, divided Americans in much the same fashion, and over many of the same issues, as the culture wars of the past three decades. Even though the religious, ethnic, and economic composition of the late nineteenth-century population differed vastly from that of Americans in the last thirty years of the twentieth century, both eras were characterized by one challenge after another to what were once considered settled cultural truths. The argument over the proper role of religion in civil government was (and is) only a subsidiary of the larger question of whether the claims of supposedly revealed religion deserve any particular respect or deference in a pluralistic society. The other cultural issues that divided Americans in Ingersolls time are equally familiar and include evolution, race, immigration, womens rights, sexual behavior, freedom of artistic expression, and vast disparities in wealth. In the nineteenth century, however, the issues were newer, as was the science bolstering the secular side of the arguments, and the forces of religious orthodoxy were stronger. The overarching question in Ingersolls time was whether any of these issues could or should be resolved by appeals to divine authority. To this Ingersoll also said no, spreading the gospel (though he would never have called it that) of reason, science, and humanism to audiences across the country. It is not an overstatement to say that Ingersoll devoted his life to freethought, the lovely term that first appeared in England in the late seventeenth century and was meant to convey devotion to a way of looking at the world based on observation rather than on ancient sacred writings by men who believed that the sun revolved around the earth.

Next page