Susan Jacoby - The Age of American Unreason

Here you can read online Susan Jacoby - The Age of American Unreason full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York, United States, United States, year: 2009, publisher: Pantheon Books;Vintage, genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Age of American Unreason

- Author:

- Publisher:Pantheon Books;Vintage

- Genre:

- Year:2009

- City:New York, United States, United States

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Age of American Unreason: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Age of American Unreason" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Abstract: Traces the current of anti-intellectualism from post-World War II to the present and argues that the nations cult of unreason is both deadly and destructive

The Age of American Unreason — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Age of American Unreason" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

CONTENTS

For Aaron Asher

If a nation expects to be ignorant and free, in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be.

Thomas Jefferson, 1816

INTRODUCTION

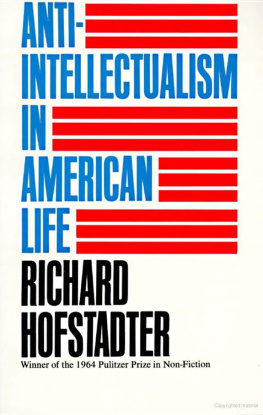

It is the dream of every historian to produce a work that endures and provides the foundation for insights that may lie decades or centuries in the future. Such a book is Richard Hofstadters Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, published in early 1963 on the hopeful cusp between the McCarthy era and the social convulsions of the late sixties. One of the major virtues of liberal society in the past, Hofstadter wrote in an elegaic yet guardedly optimistic conclusion, was that it made possible such a variety of styles of intellectual lifeone can find men notable for being passionate and rebellious, others for being elegant and sumptuous, or spare and astringent, clever and complex, patient and wise, and some equipped mainly to observe and endure. What matters is the openness and generosity needed to comprehend the varieties of excellence that could be found even in a single rather parochial society. It is possible, of course, that the avenues of choice are being closed, and that the culture of the future will be dominated by single-minded men of one persuasion or another. It is possible; but in so far as the weight of ones will is thrown onto the scales of history, one lives in the belief that it is not to be so.

I was moved by those words when I first read them as a college student more than forty years ago, and I am still moved by them. Yet it is difficult to suppress the fear that the scales of American history have shifted heavily against the vibrant and varied intellectual life so essential to functional democracy. During the past four decades, Americas endemic anti-intellectual tendencies have been grievously exacerbated by a new species of semiconscious anti-rationalism, feeding on and fed by an ignorant popular culture of video images and unremitting noise that leaves no room for contemplation or logic. This new form of anti-rationalism, at odds not only with the nations heritage of eighteenth-century Enlightenment reason but with modern scientific knowledge, has propelled a surge of anti-intellectualism capable of inflicting vastly greater damage than its historical predecessors inflicted on American culture and politics. Indeed, popular anti-rationalism and anti-intellectualism are now synonymous. I cannot call myself a cultural conservative, because that term, hijacked by the religious right and propagated by the media, is customarily used to describe a person preoccupied with such matters as the preservation of the phrase under God in the Pledge of Allegiance; the defense of marriage as an institution for heterosexuals only; the promotion of premarital chastity; and the protection of cancer patients from marijuana addiction. I do, however, consider myself a cultural conservationist, committed, in the strict dictionary sense, to the preservation of culture from destructive influences, natural decay, or waste; preservation in being, life, health, perfection, etc.

Hofstadters examination of American anti-intellectualism, an exemplary specimen of cultural conservationism, appeared at a time when the nation was taking a more critical look at the entire array of self-congratulatory pieties connected with the Pax Americana after the Second World War. The three years between the election and assassination of President John F. Kennedy generated considerable optimism among most Americans, but no group had greater reason for hope than the intellectual community. Intellectuals had become accustomed during the late forties and early fifties to a political climate that equated academic and scholarly interests with communist and socialist leanings or, at the very least, with a dangerous tolerance toward those who did harbor left-wing sympathies. Even when eggheads were not being portrayed as potential traitors, they were often dismissed as incompetents. In 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower, speaking at a Republican fund-raiser, described an intellectual as a man who takes more words than are necessary to tell more than he knows.

When the Soviet Union bruised the nations ego by launching Sputnik in 1957, it dawned on Americans that intellectuals might actually have some practical value. Public interest and money, however, were largely reserved for scientific endeavorwith its obvious importance for both national defense and bragging rights. Intellectuals who devoted themselves to scholarship or ideas with no obvious utilitarian purpose had little stature or status as far as the general public was concerned. When I moved to New York in the early seventies, I was astonished to meet intellectuals who, in the fifties, had actually believed that Adlai Stevenson could defeat Eisenhower for the presidencya wishful misconception that was surely a measure of their psychological and social distance from ordinary Americans in the nations heartland. My parents, grandparents, and most of their friends had voted for both Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman, but all I ever heard about Stevenson when I was growing up in a small town in Michigan was that he was too much of an egghead to have any understanding of ordinary people and their problems. Stevensons cultivated speech, such a strong point in his favor among his fellow intellectuals, was seen as a liability by most of the adults who inhabited my childhood world. My grandmother, who before her death at age ninety-nine boasted that she had never voted for a Republican, was able to overcome her distaste for Stevensons syntax and elevated vocabulary only by recalling the Depression and her beloved FDR. Adlai talked down to people, she recalled, and he didnt have the common touch. Ike had the common touch and I loved him, but in the end, remembering which party gave us Social Security and which party couldnt care less about starving old people, I just couldnt bring myself to vote Republican.

Kennedy, by contrast, managed the tricky feat of displaying his intelligence and educationhis manner of speaking was every bit as polished and erudite as Stevensonswithout being seen by the public as a snooty intellectual. The public was right: Kennedy was no intellectual, if an intellectual is, to borrow Hofstadters definition, someone who in some sense lives for ideaswhich means he has a sense of dedication to the life of the mind which is very much like a religious commitment. Few politicians of any era, in any country, could qualify as intellectuals by that strict standard. One of the most remarkable characteristics of Americas revolutionary generation was the presence and influence of so many genuine intellectuals (although the term had not been coined in the eighteenth century). Men of extraordinary learning and intellect were disproportionately represented among the politicians who wrote the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution and led the republic during its formative decades. True to Enlightenment values, they saw no contradiction between their roles as thinkers and actors on the public stage: the founders would have been astonished by the subsequent development of what Lionel Trilling would describe in 1942 as the chronic American belief that there exists an opposition between reality and mind and that one must enlist oneself in the party of reality.

Kennedy spoke and wrote frequentlyand had done so long before he became presidentof the need for American society to abandon its parochial twentieth-century image of an inevitable division between thought and action and return to an eighteenth-century model in which learning and a philosophical bent were thought to enhance political leadership. His government appointments reflected that philosophy; when it came time to fill important jobs in his administration, Kennedy hired prominent academics in numbers that provided clear evidence of his comfort in the presence of men (though not women) of ideas. The knowledge that the new president had sought out such undeniable eggheads as John Kenneth Galbraith, Richard Neustadt, Richard Goodwin, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., and Walter Heller did much to elevate public respect for the intellectual community, and intellectuals themselves were sometimes overwhelmed by simultaneous sensations of gratification and guilt at the newly apparent possibilities of power and its attendant material rewards.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Age of American Unreason»

Look at similar books to The Age of American Unreason. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Age of American Unreason and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.