Contents

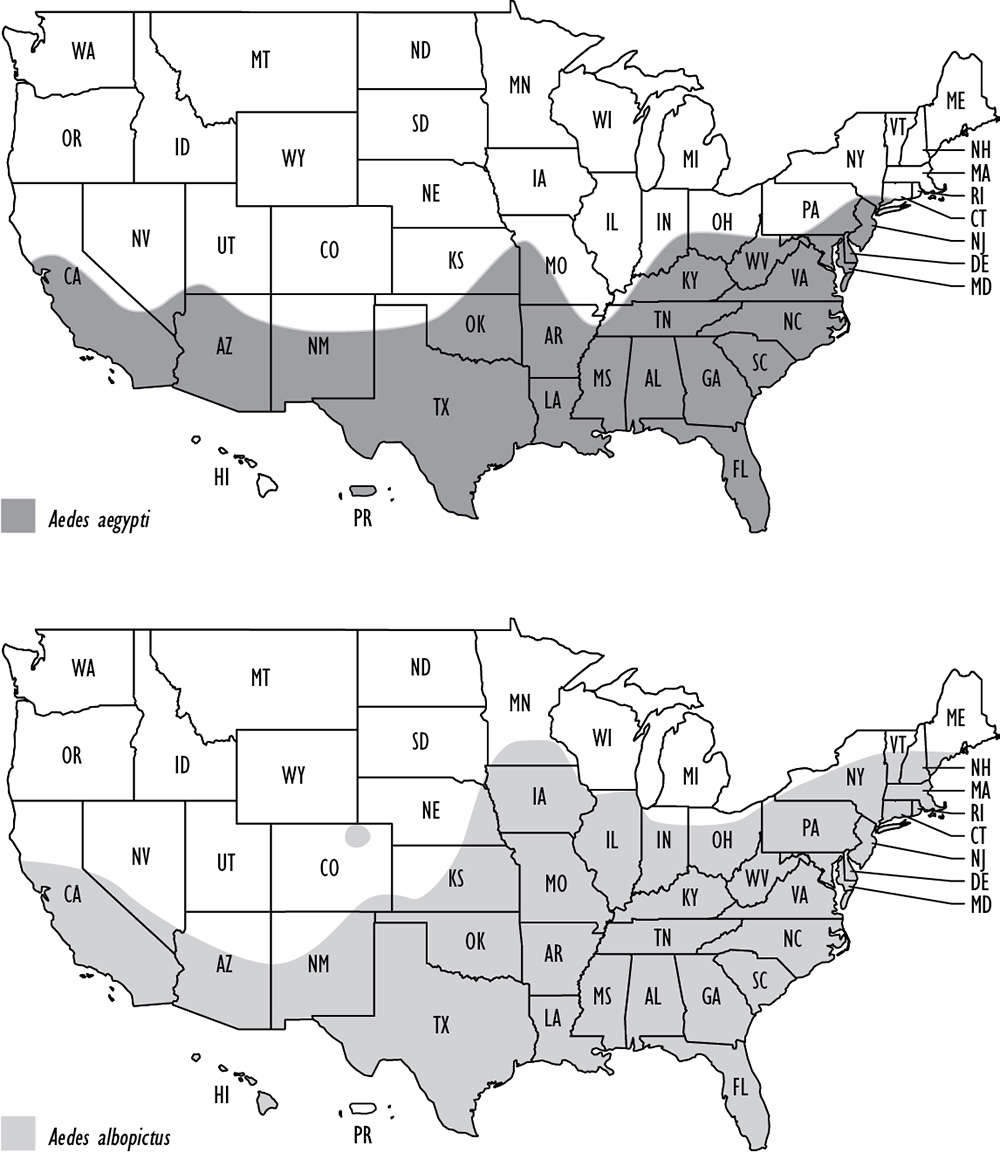

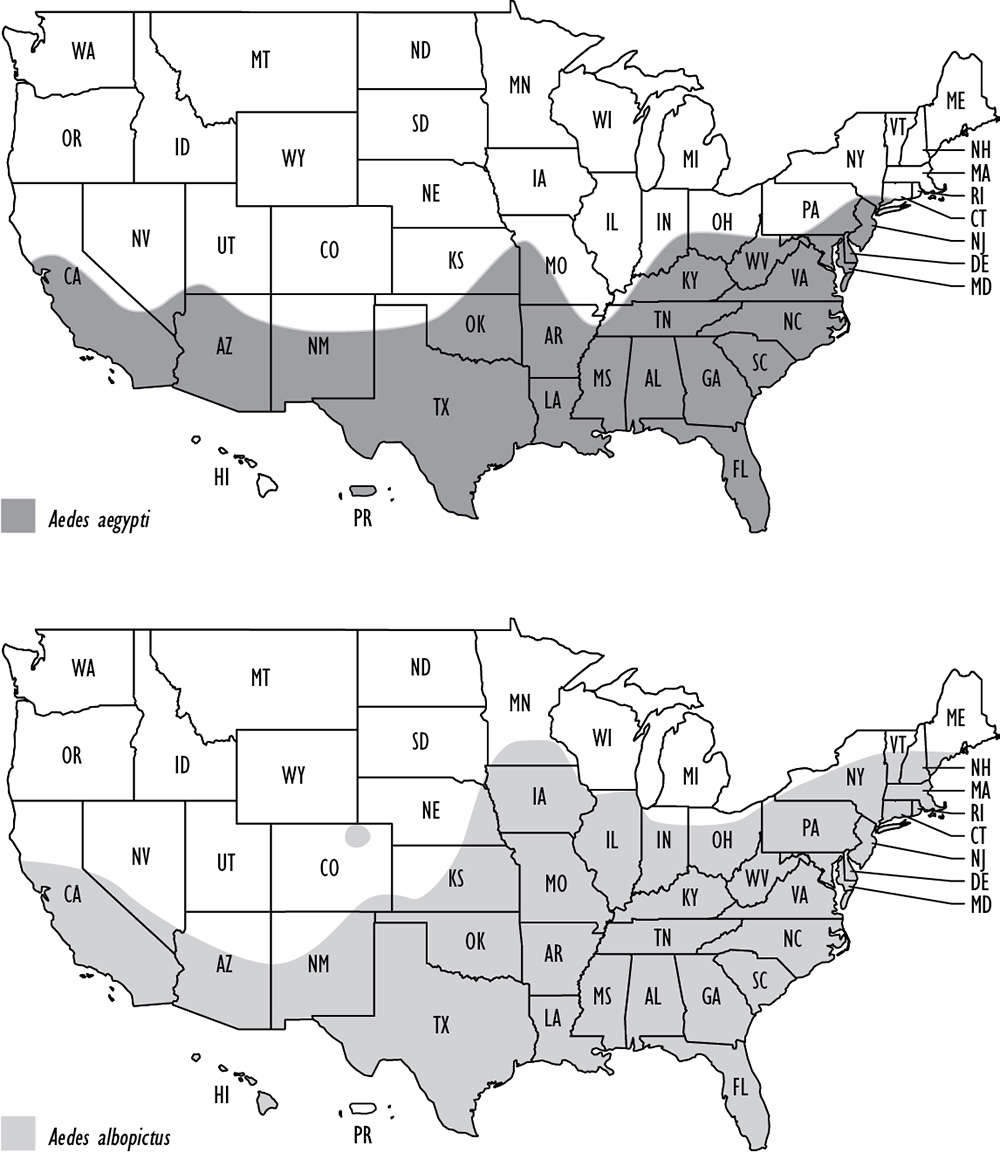

Estimated range of Aedes albopictus and Aedes aegypti in the United States, 2016. Redrawn from a map from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

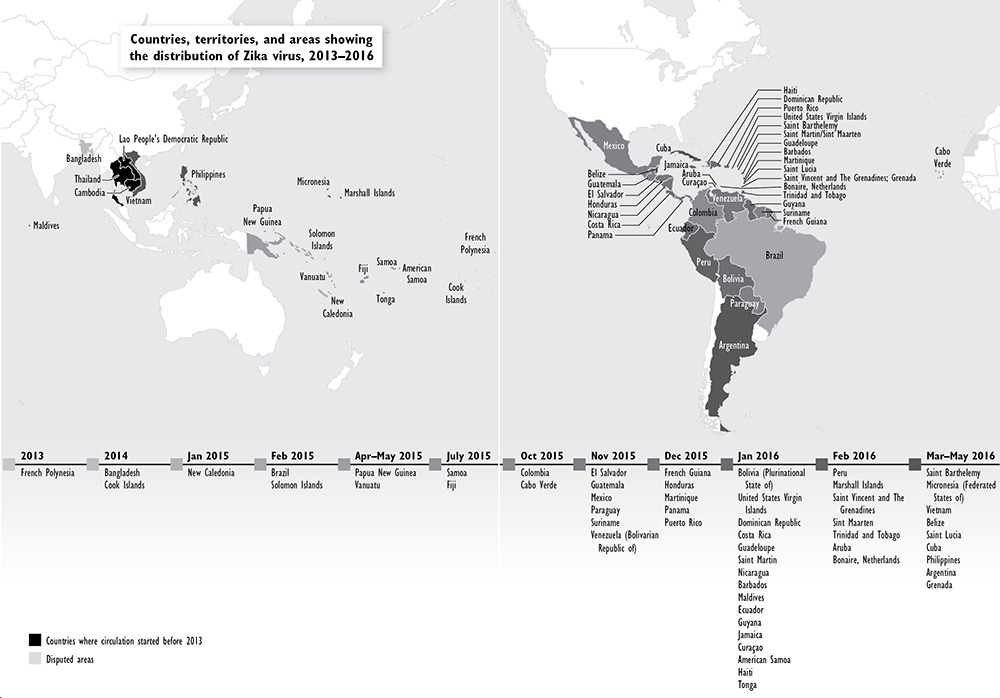

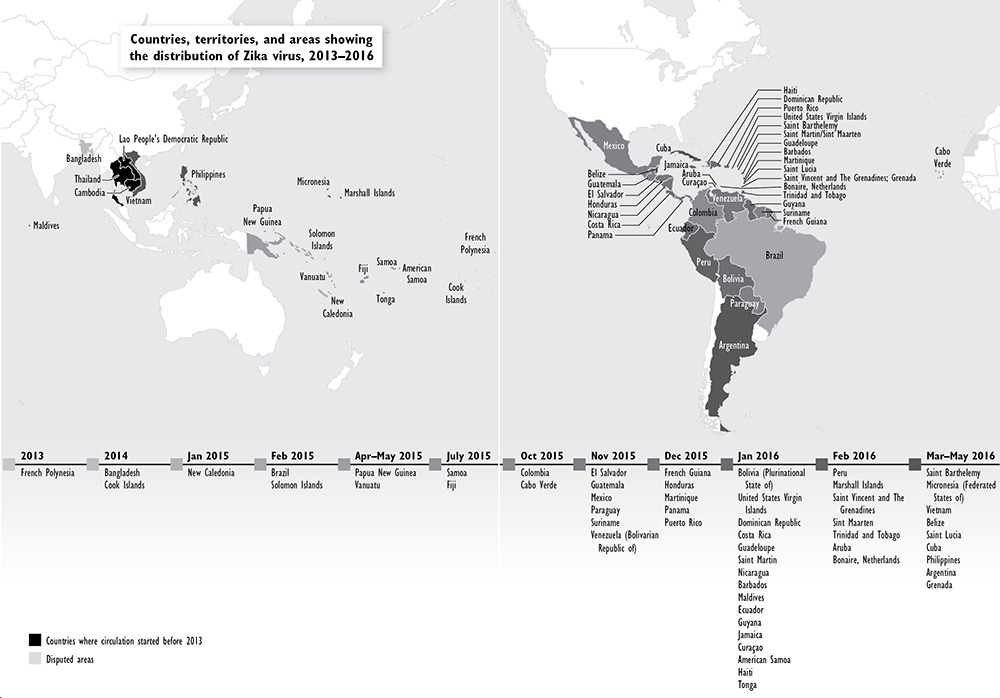

Countries, territories, and areas showing the distribution of Zika virus, 20132016. Redrawn from map printed in WHO, Situation Report: Zika Virus, Microcephaly, and Guillain-Barr Syndrome, May 26, 2016, p. 4, http://www.who.int/emergencies/zika-virus/situation-report/en/. 2016 by World Health Organization.

ZIKA

I N A UGUST 2015, something strange began happening in the maternity wards of Recife, a seaside city perched on the northeastern tip of Brazil where it juts out into the Atlantic.

Doctors, pediatricians, neurologists, they started finding this thing we had never seen, said Dr. Celina M. Turchi, an infectious diseases specialist at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, Brazils most famous scientific research institute.

Children with normal faces up to the eyebrows, and then you have no foreheads, she continued. The doctors were saying, Well, I saw four today, and Oh, thats strange, because I saw two.

Some of the children seemed to breastfeed well and did not seem to be ill, she said.

Others cried and cried, in a weird, high-pitched wail, as if they were in constant pain and could not be comforted.

Some had seizures, one after the other, their tiny bodies wracked by spasms. If the seizures lasted long enough, they could disrupt the babies breathing and heartbeat. Those babies often died after a few days.

Others seemed unable to flex their arms and legs, or their eyes jumped around erratically, not seeming to focus, perhaps not seeing anything.

Others did not react to noises and appeared to be deaf.

Others could not swallow. If they did not get intensive care and feeding through nose tubes, they, too, soon died.

As the horrified doctors compared notes, one thing stood out: many of the mothers mentioned that, months earlier, they had had the doena misteriosa Portuguese for the mystery diseasethat had first appeared nine months earlier in Recife, Salvador, Natal, and Fortaleza, the cities of Brazils arid northeast.

Back then, the disease had not seemed a big deal. Everyone appeared to have the symptoms: an itchy pink rash; fever and chills; bloodshot eyes; headaches and joint pains.

Nonetheless, many people had gone to local clinics or emergency rooms because they were worried. The symptoms looked like the beginning of a few diseases known to kill people. They looked like early malaria or yellow fever. They looked most like the first symptoms of dengue, a disease Brazilians feared because of its unique power to deliver the double tap: The first time you got dengue, you were miserable. It was called break-bone fever because it felt as if someone had taken a sledgehammer to your arms, legs, and neck. Still, you usually recovered. It was the second bout that could kill you. A second infectionwith a different one of dengues four strainswas worse, and had a chance of turning into dengue hemorrhagic fever. As with Ebola, you bled from your nose and your mouth, under your skin, and from your organs. If you got hemorrhagic fever, you usually died.

And the number of cases was soaring. It was a powerful El Nio year, with both temperatures and rainfall much higher than normal. The mosquitoes were intense. Brazil had 1.6 million cases of dengue in 2015, nearly triple the 2014 caseload. Everyone knew someone who had had it, and nearly 1,000 would go on to die of it.

But the doena misteriosa had not been dengue. The rash and fever and headaches were unpleasant, but they did not get worse. No one died of itunless the person was already seriously ill with something else. Almost no one was hospitalized. People went home from the hospital and told their families, The doctors say its not serious. They gave me pills for the headache, and theres no cure. But they say Ill get better in a few days. And, even if the kids get it, theyll be OK.

It was often misdiagnosed. Rumors attributed it to something in the water. Doctors thought it was an allergy, a parvovirus, or rubeola, or fifth disease, whose classic sign is called slapped cheek because it gives children bright red cheeks.

In May 2015, when the Cruz Foundation finally said it was an obscure African virus called Zika, the health minister in Brasilia sighed in relief. Zika doesnt worry us, Dr. Arthur Chioro told reporters. Its a benign disease.

There was no way to avoid the mosquitoes, so everyone got it. They groused, they joked, they empathized with each other, but it was just part of life. Things could be worse.

And then the disease seemed to start fading. Everyone had had itand no one seemed to get it again. So probably everyone was immune.

In fact, the doctors said that. As far as they knew, Zika was like smallpox, chicken pox, or measles: once youd had it, you never got it again. It hadnt been studied long enough for anyone to be sure it conferred lifelong immunity, but the protection seemed to be quite strong and long-lasting. It was not like dengue, which was worse if you got it again. It was not like malaria, which you could get year after year.

People stopped worrying.

But by then the disease was on the move. From its epicenter in northeast Brazil, it was moving west, into Colombia, Venezuela, and Suriname, and south, toward the megacities of So Paolo and Rio de Janeiro, which was struggling to get ready to host the 2016 Olympics. No alarms were raised. Mosquito control efforts, such as they were, continued apace. Compared with the other mosquito diseases aroundmalaria, yellow fever, dengue, chikungunyathis one was mild.

And then, about nine months after the disease had overrun the northeast, the babies began appearing. The babies with the tiny heads.

They gave the first notice that the doena misteriosa was by no means harmless.

Z IKA VIRUS WAS discovered in 1947, in the Zika Forest of Uganda, in a monkey.

There are hundreds of obscure viruses in the worldlittle curlicues of RNA with names like Spondweni, simian foamy, and onyong-nyong. A nasty one from the Four Corners area of the American Southwest was repeatedly renamed because the locals kept objecting to each moniker. It was first the Four Corners virus, then Muerto Canyon virus, then Convict Creek virus. It is now officially the Sin Nombre virusSpanish for no name.

Once in a while, one of the viruses leaps out of obscurity and into the headlines: Ebola. SARS. West Nile. Spanish flu. Swine flu. Bird flu.

But Zika virus is like no other. As Dr. Anne Schuchat, the principal deputy director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the worlds premier disease-fighting agency, has said, The more we learn about Zika, the scarier it gets.

It is the only mosquito-borne virus that routinely crosses the placenta to kill or cripple babies. Scientists do not know why or how it crosses the placenta when other mosquito-borne viruses like dengue, yellow fever, West Nile, and Japanese encephalitis almost never do.

Next page