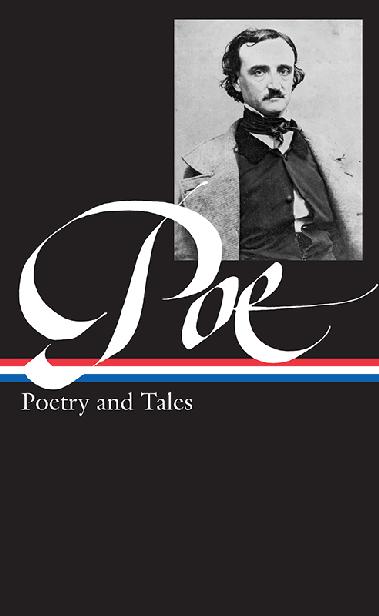

EDGAR ALLAN POE

POETRY AND TALES

Patrick F. Quinn, editor

THE LIBRARY OF AMERICA E-BOOK CLASSICS

Volume compilation, notes, and chronology copyright 1984 by

Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.

All rights reserved.

No part of the book may be reproduced commercially

by offset-lithographic or equivalent copying devices without

the permission of the publisher.

Visit our website at www.loa.org

Texts from Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe are

Copyright 1969 and 1978 by The President and Fellows

of Harvard College. All rights reserved.

Texts from The Poems of Edgar Allan Poe are Copyright 1965

by the Rector & Visitors of the University of Virginia.

All rights reserved.

The text of Eureka: A Prose Poem is copyright 1975

by Roland W. Nelson. All rights reserved.

THE LIBRARY OF AMERICA, a nonprofit publisher, is dedicated to publishing, and keeping in print, authoritative editions of Americas best and most significant writing. Each year the Library adds new volumes to its collection of essential works by Americas foremost novelists, poets, essayists, journalists, and statesmen.

Visit our website at www.loa.org to find out more about The Library of America, and to sign up to receive our occasional newsletter with exclusive interviews with Library of America authors and editors, and our popular Story of the Week e-mails.

Print ISBN 9780940450189

eISBN 9781598533873

Edgar Allan Poes

Poetry and Tales

is kept in print by a gift from

FREDERICK W. BEINECKE,

a member of The Raven Society at the University of Virginia,

and

CANDACE K. BEINECKE

to the Guardians of American Letters Fund,

established by The Library of America

to ensure that every volume in the series

will be permanently available.

The text of Eureka: A Prose Poem reprinted here was established from the authoritative documents by Roland W. Nelson. This volume also prints texts from Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe edited by Thomas Ollive Mabbott and published by The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press and texts from The Poems of Edgar Allan Poe edited by Floyd Stovall and published by The University Press of Virginia, with the permission of the publishers.

Contents

Each section has its own table of contents.

POETRY

Contents

(Poem titles not given by Poe are indicated by quotation marks)

PREFACES

Preface

(Tamerlane and Other Poems1827)

T HE greater part of the Poems which compose this little volume, were written in the year 18212, when the author had not completed his fourteenth year. They were of course not intended for publication; why they are now published concerns no one but himself. Of the smaller pieces very little need be said: they perhaps savour too much of Egotism; but they were written by one too young to have any knowledge of the world but from his own breast.

In Tamerlane, he has endeavoured to expose the folly of even risking the best feelings of the heart at the shrine of Ambition. He is conscious that in this there are many faults, (besides that of the general character of the poem) which he flatters himself he could, with little trouble, have corrected, but unlike many of his predecessors, has been too fond of his early productions to amend them in his old age.

He will not say that he is indifferent as to the success of these Poemsit might stimulate him to other attemptsbut he can safely assert that failure will not at all influence him in a resolution already adopted. This is challenging criticismlet it be so. Nos hc novimus esse nihil.

Letter to Mr.

(Poems1831)

Tell wit how much it wrangles

In fickle points of niceness

Tell wisdom it entangles

Itself in overwiseness.

Sir Walter Raleigh

West Point, 1831.

DEAR B.

***

Believing only a portion of my former volume to be worthy a second editionthat small portion I thought it as well to include in the present book as to republish by itself. I have, therefore, herein combined Al Aaraaf and Tamerlane with other Poems hitherto unprinted. Nor have I hesitated to insert from the Minor Poems, now omitted, whole lines, and even passages, to the end that being placed in a fairer light, and the trash shaken from them in which they were imbedded, they may have some chance of being seen by posterity.

***

It has been said, that a good critique on a poem may be written by one who is no poet himself. This, according to your idea and mine of poetry, I feel to be falsethe less poetical the critic, the less just the critique, and the converse. On this account, and because there are but few Bs in the world, I would be as much ashamed of the worlds good opinion as proud of your own. Another than yourself might here observe Shakspeare is in possession of the worlds good opinion, and yet Shakspeare is the greatest of poets. It appears then that the world judge correctly, why should you be ashamed of their favorable judgment? The difficulty lies in the interpretation of the word judgment or opinion. The opinion is the worlds, truly, but it may be called theirs as a man would call a book his, having bought it: he did not write the book, but it is his; they did not originate the opinion, but it is theirs. A fool, for example, thinks Shakspeare a great poetyet the fool has never read Shakspeare. But the fools neighbor, who is a step higher on the Andes of the mind, whose head (that is to say his more exalted thought) is too far above the fool to be seen or understood, but whose feet (by which I mean his every day actions) are sufficiently near to be discerned, and by means of which that superiority is ascertained, which but for them would never have been discoveredthis neighbor asserts that Shakspeare is a great poetthe fool believes him, and it is henceforward his opinion. This neighbors own opinion has, in like manner, been adopted from one above him, and so, ascendingly, to a few gifted individuals, who kneel around the summit, beholding, face to face, the master spirit who stands upon the pinnacle.

***

You are aware of the great barrier in the path of an American writer. He is read, if at all, in preference to the combined and established wit of the world. I say established; for it is with literature as with law or empirean established name is an estate in tenure, or a throne in possession. Besides, one might suppose that books, like their authors, improve by traveltheir having crossed the sea is, with us, so great a distinction. Our antiquaries abandon time for distance; our very fops glance from the binding to the bottom of the title-page, where the mystic characters which spell London, Paris, or Genoa, are precisely so many letters of recommendation.

***

I mentioned just now a vulgar error as regards criticism. I think the notion that no poet can form a correct estimate of his own writings is another. I remarked before, that in proportion to the poetical talent, would be the justice of a critique upon poetry. Therefore, a bad poet would, I grant, make a false critique, and his self-love would infallibly bias his little judgment in his favor; but a poet, who is indeed a poet, could not, I think, fail of making a just critique. Whatever should be deducted on the score of self-love, might be replaced on account of his intimate acquaintance with the subject; in short, we have more instances of false criticism than of just, where ones own writings are the test, simply because we have more bad poets than good. There are of course many objections to what I say: Milton is a great example of the contrary; but his opinion with respect to the Paradise Regained, is by no means fairly ascertained. By what trivial circumstances men are often led to assert what they do not really believe! Perhaps an inadvertent word has descended to posterity. But, in fact, the Paradise Regained is little, if at all, inferior to the Paradise Lost, and is only supposed so to be because men do not like epics, whatever they may say to the contrary, and reading those of Milton in their natural order, are too much wearied with the first to derive any pleasure from the second.