This book is for John Ellis Middleton

(19242013)

CONTENTS

MAP SYMBOLS

The maps within this Atlas make use of the following symbols:

Existing international boundary |  |

International boundary of unrecognized country |  |

State boundary |  |

Capital city |  |

Major settlement |  |

River |  |

Body of water (sea, major lake) |  |

Road |  |

Railway |  |

Mountain |  |

Volcano |  |

A note on flags

Each would-be country is presented with its national flag. In a few cases, two flags are presented, each representing a different separatist group.

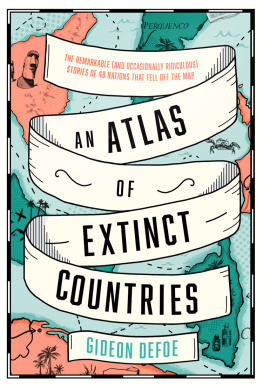

INTRODUCTION

Leopold II, King of the Belgians, was known for his prodigious appetite. He frequently ordered another entre after finishing an enormous meal, and once ate two entire roast pheasants at a Paris restaurant. It is not surprising, therefore, that he used a culinary metaphor when declaring his determination during the nineteenth-century scramble for African territory to obtain the largest possible slice of what he called the magnificent African cake.

At the Berlin Conference on Africa in 1885, Leopold secured his own private colony seventy-five times larger than Belgium, as Europes leading powers carefully divided up the entire continent between themselves. Studying a 5-metre-high wall-map of Africa, the diplomats agreed the ground rules for taking possession of its territory, and began negotiating the boundaries between their various colonies. And so concluded the final phase of the global process of European colonization that had begun more than 300 years earlier with Spanish and Portuguese explorers.

Everybody knows what todays political map of the world looks like. The bold colours and sharp boundaries show the global land surface neatly divided between sovereign states. But it hasnt always been like this. For most of human history, before the Europeans started exploring and colonizing, people lived in small cultural communities or larger civilizations that were hardly interlinked at all. With time, as more people moved more frequently and more quickly exploring, conquering, trading and travelling so the contemporary world of countries, tightly defined by their boundaries, developed.

The final phase of this process is really quite recent. It is only after the end of World War II, with the creation of the United Nations and the process of decolonization, that we came anywhere near to the map of many colours we know today. A truly global international society of countries.

Not that the political world map is static. Countries come and go. Towards the end of the twentieth century, the disintegration of the Soviet Union spawned no fewer than fifteen new states and East Germany joined its western counterpart to become a reunified country. These were quickly followed by Czechoslovakia undergoing a Velvet Divorce to create the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Already in the twenty-first century we have seen more new states emerge in Asia (East Timor), Europe (Montenegro) and Africa (South Sudan).

But at the same time, we are constantly being reminded that we live in an era of unprecedented global communication, a time when globalization is eroding the importance of the nation state. Our planet is becoming an increasingly borderless place, where national boundaries matter little to the movement of goods and investment (though the movement of migrants is another story). National governments have had their power diluted and usurped by some new actors on the global stage, including international organizations, transnational corporations and non-governmental organizations, or NGOs. A world of fixed spaces is giving way to a world of flows, and the idea of national territory is giving way to supra-national communities such as the European Union. With its echoes of Aldous Huxley, this is the New World Order.

However, while the notion of fixed territories is in one sense under threat from globalization, the rise of the internet, virtual communities and the diffusion of ideas, there is no question that the national space itself remains of great importance. Individual countries still dominate all of our lives. Much as some might like to think of themselves as Citizens of the World rather than citizens of any one nation state, they wont get very far in seeing that world without a travel document issued by their national government. Granted, the European Union has, to a large extent, done away with its internal boundaries, but the EU is still a relatively small chunk of the world. An EU citizen who ventures outside the EU can only do so legally with a passport.

Next page