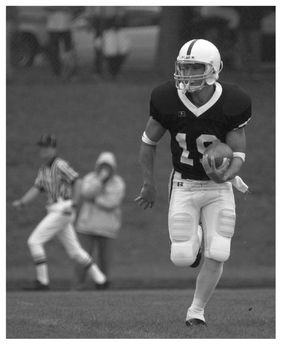

On the icy afternoon of December 6, 2003, Theresa Lannetti slipped into the home-team bleachers of Person Stadium, in the wooded college town of Williamsport, Pennsylvania. Like everyone around her, she had come to cheer the Lycoming College Warriors in their NCAA division quarterfinals against the Bridgewater Eagles. But for once Theresa did not scan the crowd for the other parents with whom shed become friends over the previous three years. She understood that few would expect her to be there, and some might feel awkward that she was.

The previous night, in the critical-care unit of a local community hospital, Theresa had wrapped her arms around her sons college roommate, Sean Hennigar, telling him that he would score a touchdown for Ricky the next day. In the morning Theresa knew that she had to stay in Williamsport and lose herself in the familiar sounds of the game. She watched as Rickys teammates jogged out from the locker room; she registered the clenched jaws and fists of his best friends; and then she glimpsed the 19s scrawled in eye black across their arms, sleeves, and pant legs. The cheerleaders rose to welcome the teammore 19s, written in jagged strips of athletic tape across the backs of their jackets and with blue greasepaint on puffy cheeks streaked with tears. Theresas own eyes remained dry until she looked across the field to see yet another 19, some fifteen feet tall, shoveled into the snowy hillside alongside the visitor stands. As Theresa watched, the artist put down his shovel and flopped onto his back, adding one perfect snow angel and then anothertwo asterisks above her sons number. Perhaps they stood for the two team records that Ricky Lannetti had set that season: six pass receptions in a single game and seventy over the regular season. Overhead, the clouds began to part for the first time that week.

The first snowstorm of the winter had arrived the previous Tuesday, dusting the field as the Warriors finished afternoon practice. The forecast of weeklong blizzard conditions did not dampen the campus-wide excitement over the NCAA division quarterfinals, with expectations high that this would be the season Lycoming would advance to the semifinals, having fallen short the previous six years. Ricky had started coughing that morning, and near the end of the blustery cold practice, a wave of nausea forced him to sit out the final plays. When Theresa called from Philadelphia the next day, Ricky cut her short. Mom, I cant talk right now. I dont feel so good, he said. Ill be fine. Its just one of those twenty-four-hour things. I gotta throw up now, okay?

Theresa told herself that Ricky was probably righthed be fine by the weekend. As always, she looked forward to watching her son play and didnt even mind the 180-mile trip from her row-house neighborhood in northeast Philly to Williamsport, the central Pennsylvania college town where Ricky was halfway through his senior year as a criminal justice major. While Theresas marriage to Rickys father had ended in 1991, their sons sports, especially football, kept family and mutual friends bound together around practice schedules, games, and postgame celebrations. In grade school Ricky had a reputation as a mighty mite, always among the smallest on the field but also the hardest to catch or evade. Other kids his age could never understand how a guy who barely reached their shoulders could hit so damn hard or arc into the air, as if from nowhere, to snag a ball. By the time Ricky reached high school, Theresa was cheering more often than cringing when her son withstood tackles that should have brought down someone twice his size. She even begrudgingly accepted the fact that there was no way she could drag him out of a game, even when she knew hed been hurt. In his four years playing for Lycoming, he had missed only one game, and that for a badly twisted ankle that he insisted was fine after a week.

But the days leading up to the teams quarterfinal game had Theresa worried. Ricky was still throwing up when she called back on Thursday. You cant ignore this! she insisted. You have to have someone check this out. She phoned the head trainer, Frank Neu, who promised to take Ricky to see his wife, a family physician, to rule out anything more serious than the flu that had been downing students sincethe Thanksgiving break. That afternoon Stacey Neu listened to Rickys lungs. They sounded clear. She took his temperatureslightly elevated. With his main symptoms being nausea, fatigue, and achiness, all signs pointed to the flu. Antibiotics wouldnt help, she explained, as they kill bacteria, not viruses.

The snow was still falling across Pennsylvania on Friday morning when Rickys legs began to ache. His roommates, Sean Hennigar and Brian Conners, pushed sports drinks and water, figuring that Ricky was dehydrated from vomiting. That evening the snow slowed Theresas drive out of Philly to a crawl. She wasnt yet halfway to Williamsport at 9:30 p.m. when Ricky called her cell phone to say he wanted to sleep. Hed see her in the morning. But Ricky didnt sleep. And despite himself, he moaned every time he rolled over in bed. If I dont get outta here, you guys wont get any sleep before the game, he told his roommates at 4:00 a.m. He called and asked his mom to bring him to her hotel room.