To the memory of Christopher Ellis Alvarez

Que en paz descanses en tu propia isla

CONTENTS

Why should the world be over-wise,

In counting all our tears and sighs?

Nay, let them only see us, while

We wear the mask.

PAUL LAURENCE DUNBAR

Uno vive durante el dia una autobiografia

que escribe en las noches previas.

PACO IGNACIO TAIBO II

To survive the Borderlands

you must live sin fronteras

be a crossroads.

GLORIA ANZALDA

I N 1909, the fastest way to make the three-thousand-mile journey from Mexico City to Manhattan was via the Ferrocarriles Nacionales de Mxicos Aztec Limited . New Yorkbound passengers boarded the train in the evening at Buenavista Station, located just a short streetcar ride away from the Mexican capitals bustling central plazas. After picking their way through the vendors who thronged the station, offering everything from newspapers to tamales, ticketholders settled into all the comforts that first-class travel at the dawn of the twentieth century could provide: fully stocked library, smoking room, buffet car serving multicourse meals, and Pullman sleepers with private compartments and beds. As the train steamed its way north, and night gave way to the first light of a new day, the vista rolling by the windows slowly began to shift. In place of colonial cities with baroque cathedrals and cobblestone streets, passengers could glimpse haciendas with lowing herds of cattle and long rows of agave plants, then the dusty, far-flung villages, rugged mountains, and forbidding deserts of the Mexican North.

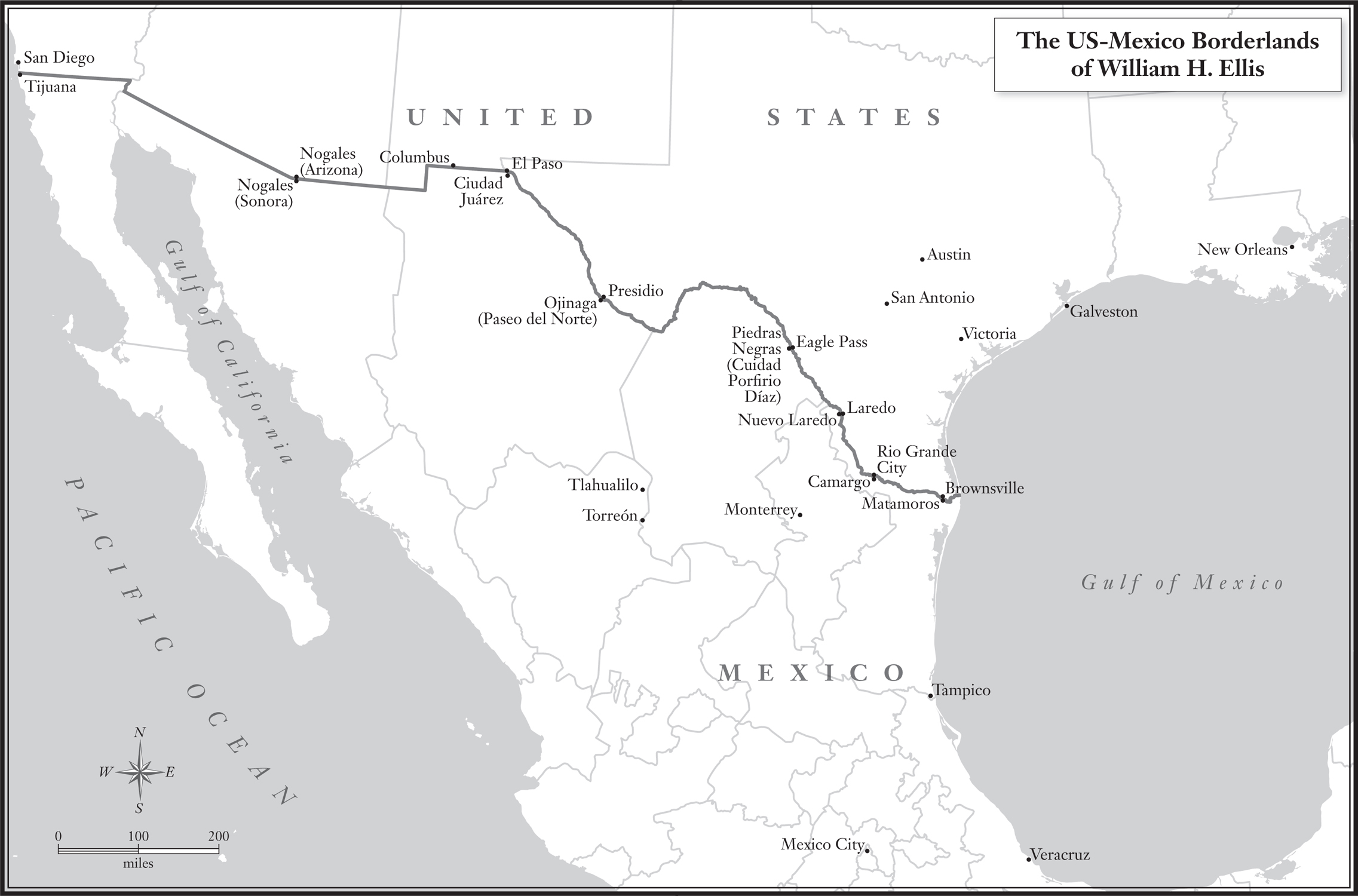

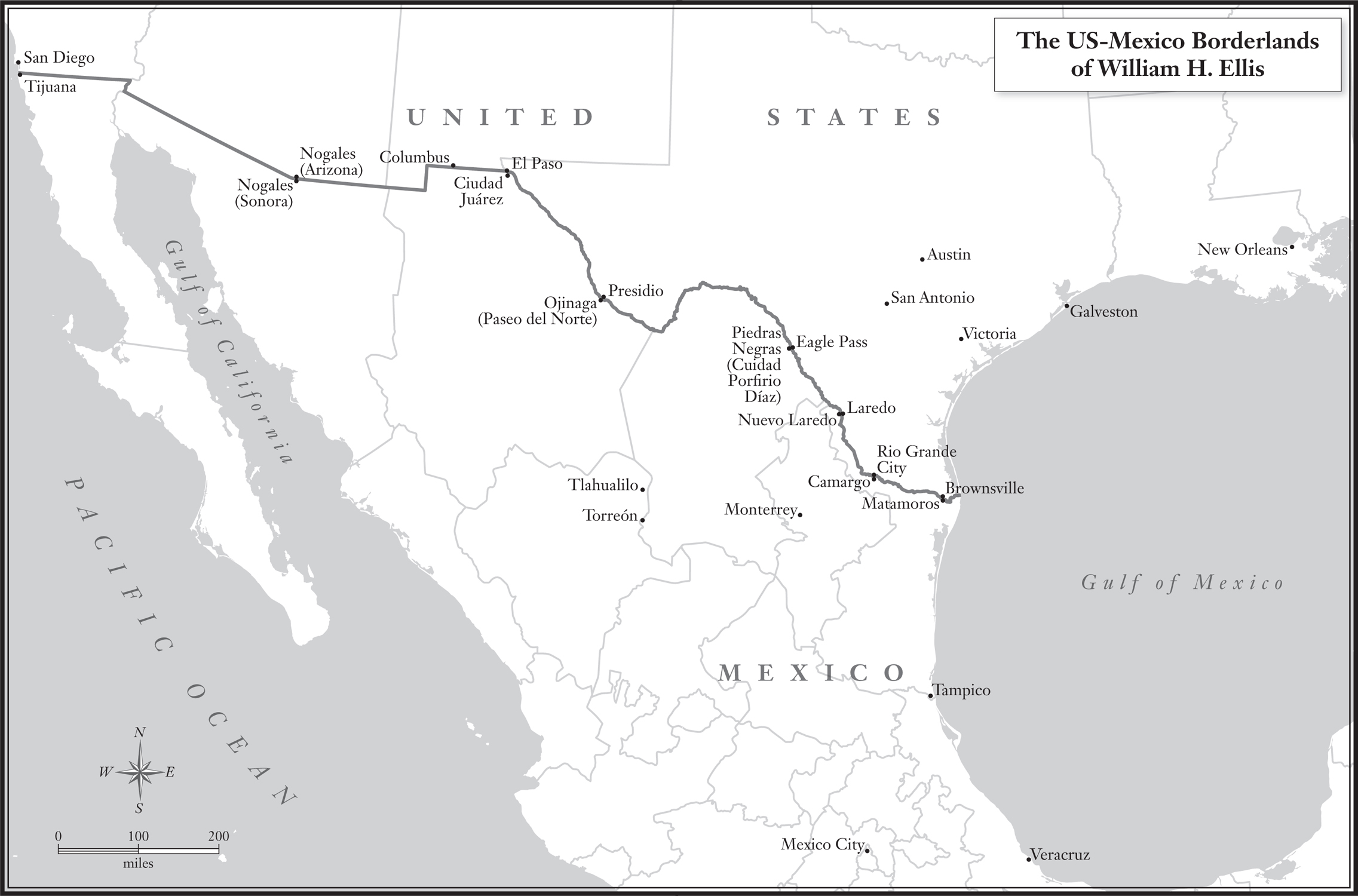

Near noon on their third day aboard the Aztec Limited , travelers reached the international borderline. Here, the twin settlements of Ciudad Porfirio Daz and Eagle Pass faced one another across the river known alternatively as the Rio Grande and the Ro Bravo del Norte, depending on whether one followed US or Mexican practice. Despite such squabbles over terminology, for much of the nineteenth century, the residents of these isolated communities had interacted more with one another than with the outside world, shuttling back and forth across the shallow, blue-green waters dividing their respective nations via a flat-bottomed ferry. With the coming of the railroad in 1882, however, this venerable ferry service found itself supplanted by the new iron bridge that enabled that marvel of the industrial age, the steam-powered engine, to complete the journey from Mexico to the United States in just a few revolutions of its piston-driven wheels. The railroad remade the geography of Eagle Pass and other border towns along the Rio Bravo del Norte such as Laredo and El Paso in other ways, too. Almost overnight, these remote outposts at the periphery of the nation were transformed, in the language of the day, to gateways between North Americas two sister republics.

For the passengers aboard the Aztec Limited , crossing the border was at once routine yet momentous. After the train journeyed across the bridge spanning the Rio Grande and pulled into the one-story depot on the eastern edge of Eagle Pass, agents of the recently created US Department of Commerce and Labor, dressed in their regulation dark blue uniforms with brass buttons, climbed aboard to inspect the passengers and their luggage. Agents evinced no interest in narcotics like heroin, marijuana, or cocaineall legal in 1909but sought instead imported delicacies: in an era of high tariffs and no income tax, the federal government raised the bulk of its revenue through duties on luxuries such as lace, silk, jewels, watches, and cigars.

Next, in a measure that spoke volumes as to the borders role in establishing personal identity as well as national territory, these same agents compiled a report of inspection on all incoming passengers, detailing each arrivals name, place of birth, occupation, and final destination. The United States would not require passports until 1914, so rather than focusing on reading ones documents, this procedure hinged instead on reading, as it were, ones person: determining the truth of an individuals stated identity through language, dress, physical traits, and other clues. On ordinary passenger trains, agents exercised particular vigilance against Chinese or Japanese laborerswho in an effort to evade the United States restrictions on Asians often disguised themselves as Mexicansas well as immigrants considered anarchists, paupers likely to become public charges, or the possessors of loathsome or dangerous diseases. But on a luxury train like the Aztec Limited , catering to well-to-do businessmen and upper-class tourists, agents more often than not took individuals declarations of identity at face value.

On the morning of March 14, 1909, however, a tall man with penetrating brown eyes and carefully groomed mustache, attired in the latest fashionspats, top hat, tailored three-piece suit, gold watch chain and jeweled fob draped across a powerful barrel chestcaught the eye of authorities in Eagle Pass . Like the others on the Aztec Limited , the passenger had begun his journey from Mexico City in a first-class Pullman. Once he crossed the border into the United States, however, a new question arose. What race was he? For despite his elegant appearance, his skin had a somewhat swarthy toneand, unlike Mexico, the Texas of 1909 possessed segregation laws, designed to limit contact between blacks and whites in everything from schools, restaurants, libraries, graveyards, and hotels to railroad cars.

When asked, the newcomer insisted that he was a Mexican entrepreneur, on his way back to his office on Wall Street after negotiating the purchase of several rubber plantations in his homeland. His name, he offered, was Guillermo Enrique Eliseowhich, for those who might have trouble with foreign pronunciations, could be translated into English as William Henry Ellis. Moreover, as an ethnic Mexican, he was legally white and not subject to Texass segregation statutes.

At least a few on the train, however, had caught wind of half-whispered rumors circulating along the border that, for all his obvious wealth and sophistication, Eliseo might not be the well-to-do Mexican he claimed to be. Could it be that his olive complexion was a product not of a Hispanic background but rather of a covert African American one? Dismissing such assertions, Eliseo refused the conductors attempts to relocate him to the negro coach after the Aztec Limited reached US soil. Only once the train crew summoned the local sheriff, charged with enforcing Texass segregation statutes, did Eliseo grudgingly obligebut not before vowing to all within earshot that he would spend hundreds of thousands of dollars, if necessary, to sue the railway for the humiliation of forcing him to ride in the Jim Crow car.

W HO WAS G UILLERMO Enrique Eliseo? Such was the question many found themselves asking at the turn of the last century as this dapper yet enigmatic figure flitted in and out of an astonishing array of the eras most noteworthy eventsscandalous trials, unexpected disappearances, diplomatic controversiesmost linked in one way or another to Latin America. Uncertainties about his ethnicity did not confine themselves to his 1909 border crossing at Eagle Pass. During his years in the public eye, commentators proffered a kaleidoscope of possibilities. The New York World observed that Eliseo has the looks and dash of a Spaniard and speaks several languages. Denvers Evening Post asserted that Eliseo was a wealthy Mexicanin fact, without doubt the wealthiest resident of the City of Mexico. Others maintained that he was of Hawaiian blood or a Cuban gentleman of high degree. Editors at the Kansas City Star , however, cautioned that the stories of his Hawaiian ancestry are not to be credited, while an equally suspicious correspondent to the Baltimore Sun discounted the rumors that Eliseo was of Cuban, Brazilian, Mexican and no one knows what other Latin-American extraction. Concluded the New York Sun : Just where [Eliseo] came from no one hereabouts seems to know.

Next page