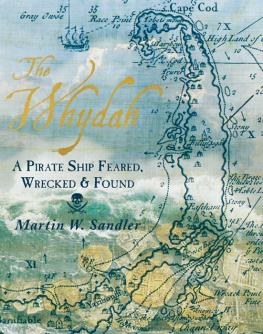

I N 1984, newspaper headlines and television newscasts around the world announced that the wreck of the pirate ship Whydah had been discovered off Cape Cod. The Whydah was the first sunken pirate ship ever to be found. It had lain undiscovered for so long almost three hundred years that many had come to wonder if it had ever existed, if the incredible stories they had heard about the ship, its crew, and its amazing cargo of treasure were actually myths.

The stories connected with the Whydah are tales of pure adventure, populated by colorful characters, including one of the boldest and most successful pirates ever. Filled with outlandish deeds, amazing courage, barbarous acts, triumphs, and tragedy, the stories are made even more extraordinary by the fact that they are true.

The saga of the Whydah continued after it went down, and this part of its story is, in many ways, as fascinating as the tales of deeds and misdeeds aboard the ship when it rode the high seas. In the ordinary course of events, ships that outlive their usefulness are stripped or broken apart. But over the centuries, many have been shipwrecked so many that much of human history lies hidden beneath the waves. Famed oceanographer Robert Ballard has described shipwrecks as the pyramids of the deep. I think theres more history in the deep, he has said, than in all the museums in the world combined.

When a ship sinks, it becomes a time capsule. If it is salvaged, like the Whydah, it provides evidence of what ships were like and what life was like at the time of its sinking.

The Whydah was not only the first sunken pirate vessel to be discovered; it was also the first pirate ship to be excavated. Marine archaeologists have uncovered artifacts in its wreck that have changed our entire notion of who the pirates were and how they lived. Pirates have long been the subject of legend and literature and considerable imagination. But the true story of the pirates is every bit as fascinating as the fiction they spawned.

Martin W. Sandler

Cotuit, Massachusetts

I N FEBRUARY 1717, Captain Lawrence Prince was heading home, back to England, on his ship the Whydah, which was loaded with a fortune in gold, silver, and other valuable goods. It was the final leg of the magnificent vessels highly successful maiden voyage.

Formally named the Whydah Gally, the ship was built in 1715 for Sir Humphry Morice. A member of the British parliament, Morice was one of the most active slave traders of his day. His new ship, named for the infamous West African slave trading port Ouidah, was constructed to carry captured Africans to Caribbean plantations, where sugar, rice, tobacco, indigo, and other highly valued products were grown. There the captives would be sold into slavery.

Morice selected Lawrence Prince to be the ships captain. It was an understandable choice, as Prince was well suited to command a ship constructed for such a brutal purpose. He had spent several years serving under the feared Welsh privateer Captain Henry Morgan, who had been employed by England to capture or destroy Spanish ships and raid Spanish towns in the Caribbean. That Prince could be ruthless in carrying out his duties is evidenced by an official Spanish government report of a raid he led on a town in Nicaragua. Prince, the report stated, made havoc and a thousand destructions, sending the head of a priest in a basket and demanding 70,000 pesos in ransom.

In 1671, Prince helped lead Morgans raid on Panama. His share of plunder from the attack allowed him to retire to Jamaica, where he lived as a prosperous landowner for more than forty years before being given command of the Whydah. It was an impressive ship. Three-masted and 102 feet long, it featured the most advanced nautical technology available, including state-of-the-art steering mechanisms and the most up-to-date navigational and sounding equipment. It was armed with eighteen cannons and had room for ten more. Extremely strong, the Whydah could carry three hundred tons of cargo. Most impressive of all, it was fast, capable of traveling over the waves at the then-amazing speed of just over thirteen knots, or fifteen miles per hour. Among the ships most visible features was a long platform on its deck for captives who could not fit in the vessels huge hold during the long voyage from Africa to the Americas. They would be shackled to the platform, lying side by side, exposed to all weather, with a barrier separating the male prisoners from the women and children, many of them their wives, sons, and daughters.

Early in 1716, with Captain Prince at its helm, the Whydah set sail from England loaded with cloth, firearms, gunpowder, liquor, hand tools, utensils, and other trade goods. The ship sailed along the coast of West Africa, passing what is today the Gambia, Senegal, and Nigeria, until it reached Ouidah, its namesake port. There Prince exchanged his cargo for almost four hundred slaves. The price Prince paid for each of the slaves is not known, but records from the Royal African Company, one of the worlds largest traders in slaves, show that in 1731, the company bought forty slaves in Ouidah by trading 337 rifles, 40 muskets, and 530 pounds of gunpowder.

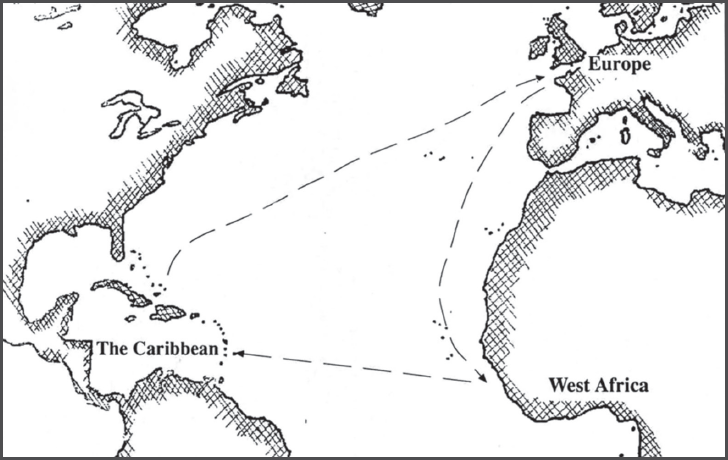

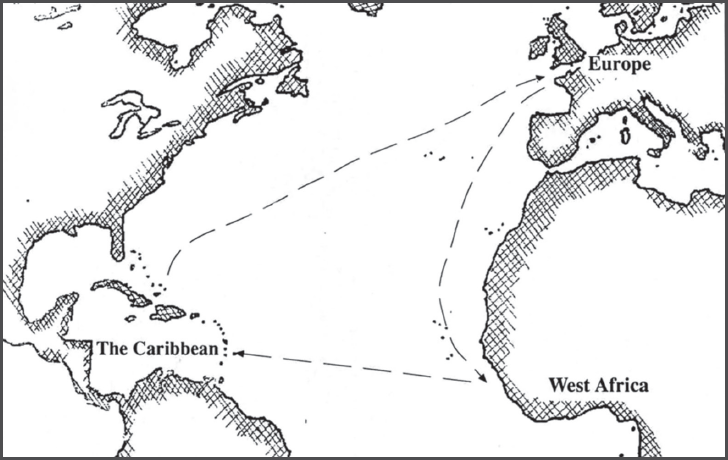

The Whydahs voyage from England to West Africa was the first leg of the infamous slave-trading route known as the Triangular Trade. Once the four hundred slaves were crammed aboard his ship, Prince set sail across what was called the Middle Passage, headed for the Caribbean island of Jamaica. It was an almost ten-week voyage, during which nearly 20 percent of the captives died. The slavers did not provide enough food, and they packed their captives as tightly as possible. In these conditions, diseases such as smallpox, measles, and dysentery often spread out of control. Some of the slaves tried to commit suicide by throwing themselves overboard, but they were prevented from doing so by the special netting installed all around the deck. Despite their ordeal, 312 unfortunate souls survived and were dropped off at a huge Jamaican sugar plantation, where they were forced to work for the rest of their lives. Prince, on the other hand, received a fortune in gold, silver, and other valuables from the plantation owners to take home to the Whydahs owners in exchange for having delivered his human cargo.

This map shows the route of the Triangular Trade in which ships sailed from England and other European countries to the coast of West Africa loaded with goods to exchange for slaves. The second leg of the journey brought the slaves from Africa to the Caribbean, where slave labor was used by plantation owners. The slaves were traded for gold, silver, and other valuables, which were shipped back to Europe for the final leg of the journey.