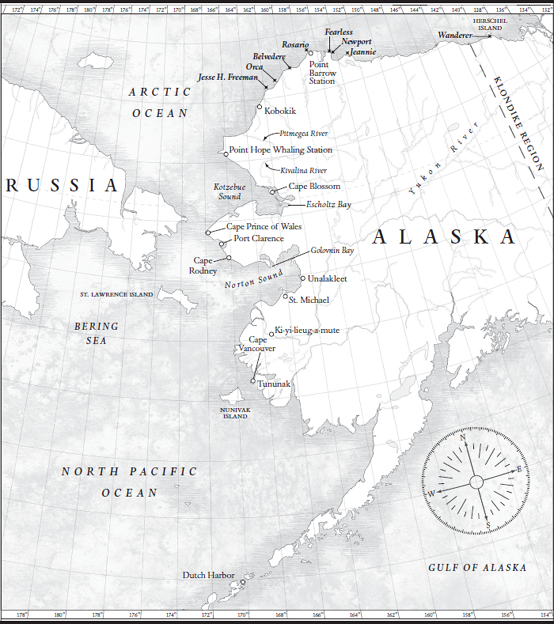

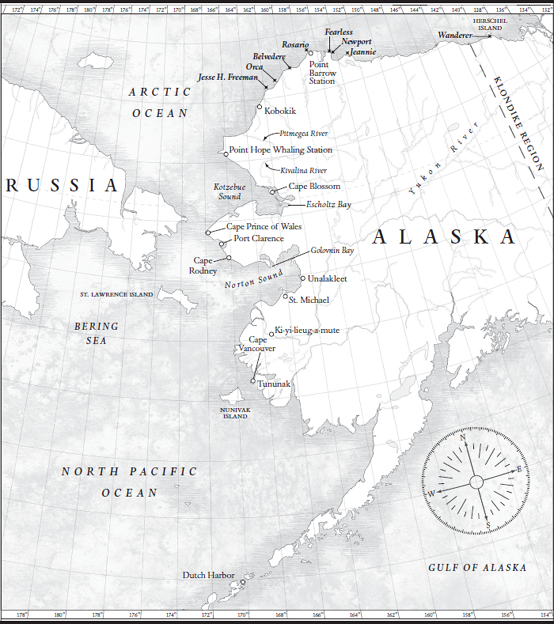

This map, based on one drawn about 1887, shows the key places in the Arctic where the story you are about to read took place, from the tiny village of Tununak, in the southwest corner of Alaska, to Point Barrow, the farthest point north. The names indicated in the waters off Point Barrow are those of the whaling ships that, in 1897, became trapped in the ice there.

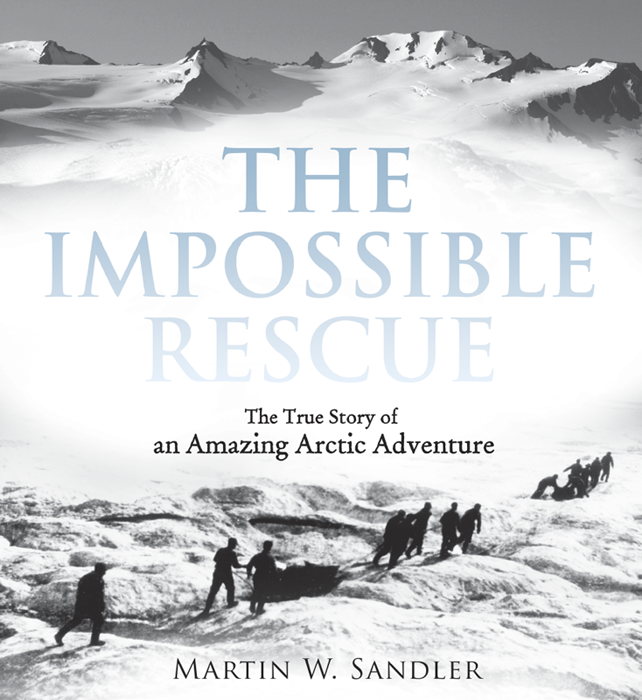

The book you are about to read tells the story of one of the worlds most amazing adventures, a saga based on arguably the most daring rescue plan ever devised. It is a story filled with extraordinary courage, unprecedented personal sacrifices, human failings, and continual suspense.

The people you are about to meet were as remarkable as the story they lived. Called upon to accomplish what most believed to be impossible by no less a person than the president of the United States, they were thrust into the harshest and most dangerous environment in the world, an immense region of ice and snow with temperatures that fell to as low as sixty degrees below zero, a place where a persons every step might very well be his last. You will also meet an extraordinary ship and its crew. And throughout the book, you will encounter the unique and often misunderstood people who had long made this harsh region their home and will discover the essential role they played as a miracle in the Arctic unfolded.

In order to do it justice, I have told this story, wherever appropriate, through the words of those who took part in it. This has been made possible by the existence of reports, diaries, journals, letters, and detailed reminiscences written by the principal characters. Researching the illustrations for the book yielded a most welcome and important surprise. Initially, I was delighted to discover photographs that had been taken during the actual adventure. I became even more thrilled when I was later able to determine that many of the pictures were taken by one of the most important characters in the story.

Adventure, suspense, almost unimaginable heroics these are just some of the ingredients of a story made even more remarkable because it really happened. But above all, the story is a celebration of the human spirit, one that, in the most dramatic fashion, reveals how brave men and women will risk and sacrifice all to help those in peril.

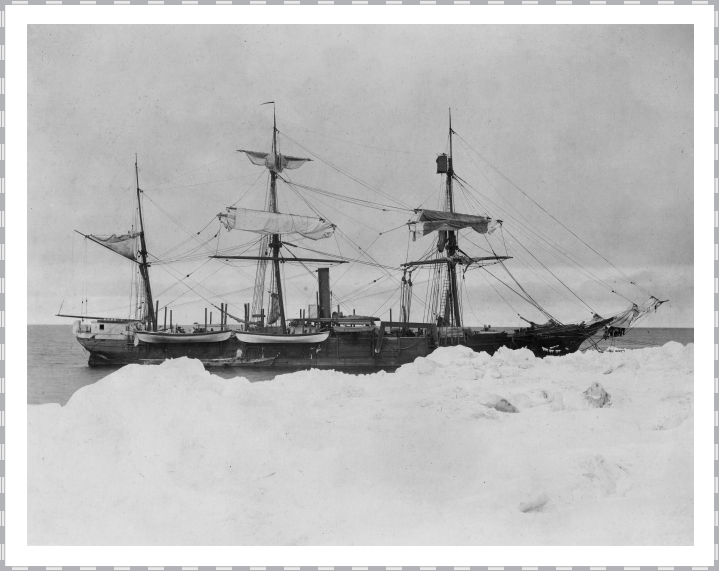

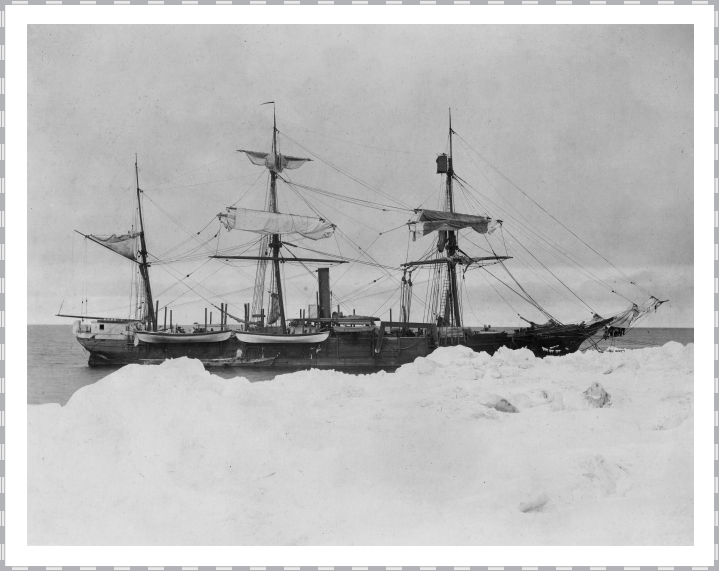

The whaleship Alexander approaches ice-filled Point Barrow, Alaska. Never in all mans history, historian Everett S. Allen would write, has there ever been anything comparable to whaling in terms of what it demanded of those afloat who pursued it, or the vessels in which they sailed.

Benjamin Tilton, the captain of the whaleship Alexander from San Francisco, was in the final month of a whaling trip. He and the captains of the Orca, the Belvedere, the Jesse H. Freeman, and the Rosario were convinced that they would have a few more weeks of fair weather to fill their holds before heading south.

The Alexander and the other vessels were hunting for bowhead whales. The weather had been excellent, enabling them to catch scores of the mammoth creatures, enough to provide tons of the bowheads enormous bones, which were turned into profitable, commonly used items such as buggy whips, clothespins, carriage wheels, pie cutters, and, most important of all, the corset stays that helped women throughout the world enhance their figures. It was only the first of September, 1897, yet, without warning, the temperature plunged dramatically and heavy ice came sweeping in from far out at sea. So much ice formed in the north off Point Barrow, Alaska, that the ships were forced to lay anchor to wait for favorable winds to drive the ice away.

The winds that Captain Tilton had silently prayed for came, but they were hardly favorable. With them they brought a whole new unbroken pack of ice, a mile and a half long and a half a mile wide. Looking out at the ice, which now seemed to stretch on forever, and then over the first mates shoulder, Tilton noticed what the officer had entered in his log. We have to get out[;] the ice [is] bad this year.

The weather was not the only thing troubling Tilton. He was outraged at the behavior of the other captains. From the moment they had become icebound, they had taken to gathering aboard the Belvedere for a continuous round of drinking parties. This went on for several days, James Allen, one of the engineers aboard the Freeman, would later write. The captains didnt pay much attention to the ice, or to anything else during their parties.... They didnt regard the situation as serious. They reckoned that when a noreaster came it would drive the ice out again.... A few days later came the northeast wind, and oh boy, she blew, believe me! But the ice never moved. These partying captains now commenced to realize that their ships were in a dangerous position.

The whaler Belvedere was one of the most well-traveled ships of its time. As author Richard Ellis stated, In their search for [whales] the roving whalers opened the world, much as the explorers of the sixteenth century had done in their quest for the riches of the Indies.

As Tilton knew, spending a winter in the ice meant surviving months of almost twenty-four-hour-a-day darkness and temperatures that plummeted to as far as sixty degrees below zero. It meant never knowing when the ice would suddenly move with a force that could splinter a ship beyond recognition. And that was far from all. The whaleships had expected to leave the Arctic by mid-November. None of them carried nearly enough food and other supplies to sustain the men through the winter.

Captain Tilton was determined to get himself out of this icy trap. Fortunately, his ship was imprisoned in a spot where the ice was not yet quite as thick as that surrounding the other vessels. Like most of the other ships, the