Contents

Guide

Martin W. Sandler

America

Through the Lens

Photographers Who Changed the Nation

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY NEW YORK

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

I am, as always, grateful for the help and support of my agent, John Thornton. I also wish to thank Carol Sandler for her many contributions. I am particularly indebted to Reka Simonsenher skill and guidance go well beyond her acknowledged editing skills and shine through on every page.

This book is dedicated to all the men and women, amateur and professional, who have used their cameras to remind us of all that is good in our lives and all that needs to be corrected.

INTRODUCTION

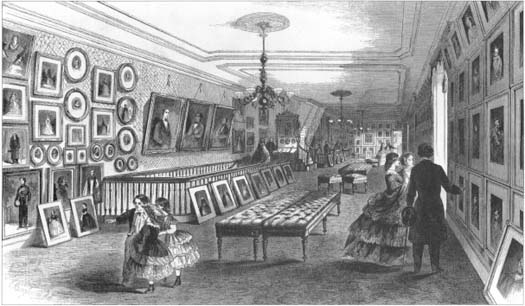

For those of us accustomed to being surrounded by photographs, it is hard to imagine what a sensation they caused when they were introduced in 1839. For the first time people could have exact likenesses of themselves to give to friends and loved ones. People could also see what the celebrities of their day really looked like, individuals they had previously only read about.

As more efficient types of cameras were invented, photographers began to use them for purposes other than making portraits. Some took striking pictures of the landscape surrounding them and of places around the world that few people would ever have the chance to visit. Others captured images of important events as they were happening, changing forever the way the world received its news. Still other photographers took pictures whose sole purpose was to convey beauty, photographs that would earn their place in museums and galleries alongside paintings as true works of art. In modern times, such innovations as easy-to-use disposable cameras and instant and digital photography have combined to make taking pictures the most popular hobby the world has ever known.

The camera has never been more important or far-reaching than when it has been in the hands of photographers who have dedicated themselves to bringing about change. From photographys earliest days, there have been cameramen and camerawomen who have been driven to, as photographer Lewis Hine so aptly put it, show the things that need to be appreciated; show the things that need to be changed.

That is what this book is all about. In it you will meet men and women who, often against great odds, brought about needed change. You will, for example, encounter Mathew Brady, Americas first prominent photographer, whose pictures dramatically changed the nations attitude about war. You will meet Lewis Hine, who spent years of his life taking pictures of the millions of young children working from dawn to dusk in factories, canneries, and mines, pictures so powerful that they were instrumental in the abolishment of child labor. And you will be introduced to Frances Benjamin Johnston, whose photographs of African Americans in the postCivil War years gave the world a portrayal of these people far different from any that had ever before been presented.

These are but three of the talented and dedicated people you will meet. All were highly skilled. Many of their pictures stand on their own as photographic masterpieces. But their true legacy is the way they brought about needed changes in attitudes and conditions, and in doing so helped make America, and the world in general, a better place in which to live. There can be no greater contribution.

Martin W. Sandler

COTUIT, MASSACHUSETTS

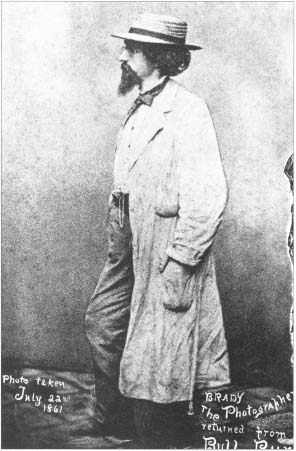

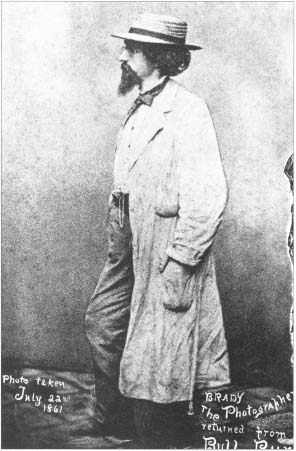

Mathew B. Brady

(18231896)

Changing the Way We View Our World

A spirit in my feet said go, and I went.

With that simple statement Mathew B. Brady explained why he had risked both his life and his fortune to give America a photographic record of the Civil War. Brady had already changed the way people viewed their world by becoming a pioneer in the field of photography. Soon he would change the nations attitudes toward war.

Born in 1823 in Warren County, New York, Brady became fascinated with paintings as a child and decided he wanted to be an artist. An ambitious young man, he was able, at the age of sixteen, to gain an apprenticeship with the well-known painter William Page.

Mathew Brady said that from the first. I regarded myself as under obligation to my country to preserve the faces of its historic men and mothers.

On a fateful day in 1839, Page introduced his apprentice to a fellow artist and friend, Samuel F. B. Morse. A professor of painting and design in New York, Morse was a man of many interests and had just completed his first invention. He called it the telegraph, and it would revolutionize the world of communications.

But Morse already had another new interest. He had recently returned from Paris where he had met with Louis Daguerre. The Frenchman had just astounded the prestigious French Academy by demonstrating his success in capturing permanent images through the lens of a camera, something that inventors and scientists had been trying to accomplish for hundreds of years. Daguerre had shown Morse how to produce such pictures, which he called daguerreotypes, and now Morse was starting a class in the astounding new process.

To Brady, daguerreotypes were miraculous. There before him was a picture of a personnot an interpretation drawn by an artist but an exact likeness of the individual. Young as he was, Brady realized that this new invention, which would come to be called photography, would change the world. He enrolled in Morses class.

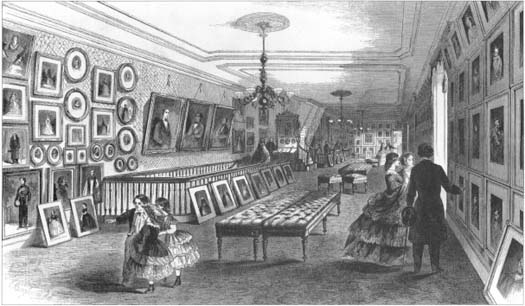

Brady quickly mastered techniques of the new daguerrotype process. He was so adept that he soon learned all that Morse could teach him. On his own, he began experimenting with ways to produce the most interesting pictures possible.

It was not easy. In those days people had to sit before the camera for as long as thirty minutes in order for an image to take. And they had to remain perfectly still. Head clamps were often used to keep subjects from moving. Because artificial lighting had not been perfected, the earliest daguerreotypes were taken outdoors in full sunlight. Many of those who sat for photographs came away with a sunburn and only a single image for their trouble, since daguerrotypes could not be reproduced.

Yet almost everyone felt that the painful experience was worth it. For the first time, people have exact likenesses of themselves to share with their relatives and friends. And most could afford it. Unlike artists portraits, which were so costly that only the wealthy could have them made, daguerreotypes were relatively inexpensive.

Soon there were daguerreotype studios in almost every city in the United States. Most of them were run by unskilled photographers who wanted only to earn a living from their work. But Mathew B. Brady took a different approach.