Copyright

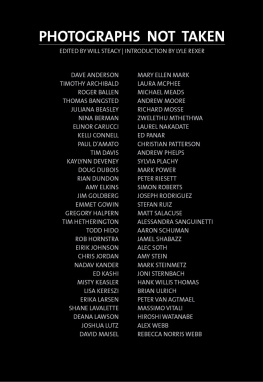

Editor: Will Steacy

Founding Editors: Taj Forer and Michael Itkoff

Design: Ursula Damm

Copyediting: Sally Robertson

2012 Daylight Community Arts Foundation

All rights reserved

eISBN 978-0-9832316-3-9

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of copyright holders and of the publisher.

Daylight Community Arts Foundation

Fax +1-775-908-5587

E-mail: info@daylightmagazine.org

Web: www.daylightmag.org

PREFACE

Photographs Not Taken is a collection of essays by photographers about moments that never became a picture. I have asked the photographers within these pages to abandon the tools needed to make a photograph and instead describe the experiences that did not pass through their camera lens. Here, the process of making a photograph has been reversed. Instead of looking out into the world through a camera lens, these essays look directly into the minds eye to reveal where photographs come from in their barest and most primitive formthe original idea. These mental negatives depict the unedited world that could not exist in a single frame .

Will Steacy

INTRODUCTION

The Art of Missing Information

by Lyle Rexer

Dear readerI use this term instead of some others that might ordinarily be appropriate to a photo book: peruser, looker, browser, viewerdear reader, you have in your hands a book of photographs that might have been taken by the Argentine fantasist Jorge Luis Borges, a book of photos without pictures. Or rather, pictures without photographs, since many of the images here are far more vivid than ones taken with a camera.

Is Will Steacys brilliant collection, then, a species of contemporary art production grown familiar since Yves Klein presented an exhibition of empty space at the Iris Clert Gallery in 1958? Is it the latest chapter in the history of voids, negations, refusals, anti-art strategies, and marketing sleights of hand that, in their way, define contemporary art? We know about architects who dont build, artists who renounce the making of objects, filmmakers who tell no stories, musicians who explore only silence, and choreographers who revel in stasis. But photographers who renounce the imagethese surely must be the last explorers of negative space. I am talking about classical photographers now, not those who have already given up on conventional camera relations in search of greater political relevance or as raids on the ineffable.

Truth to tell, the anecdotes collected here, personal as they are, reflect an aspect of the growing crisis of photography, a crisis that has to do with the self-consciousness of the genre and the broader ambivalence about the role of images in a media-saturated world. Yes, photography is a kind of atavism, a by-now instinctive response to the technologized, spectacular world, a mad cataloging that often resembles nothing so much as a vast collection of toenail cuttings. Yet these days every photograph taken by people who do it for a living arrives inside a set of quotation marks, a bracketed form of perception that says: Dont trust me! and Should I really be showing you this? and Should you really be looking? Above all, Does it matter?

There is more than a little agonizing in these reminiscences about the morally ambiguous character of photographic practice (although almost no broader theorizing about the mechanisms of image distribution and control can vitiate even the staunchest political position). These second thoughts are usually framed in very personal terms, and I want to look briefly at a few of them, because they express exactly how and why photography is not like other arts, socially, politically, or psychologically.

First off, there are many kinds of missing pictures described here (just as there are many shades of darkness). There are: pictures that could not be taken, pictures that wer e prevented from being taken, pictures that were taken and failed, pictures that were almost taken but abandoned, pictures that might have been taken but were renounced, pictures that were missed and became memories before they could be taken, and of course pictures that were taken of one thing and were really about something entirely different that could not be shown directly. The artists have in some cases also rewritten Steacys directive, supplying descriptions of pictures other people took, for better or for worse. See Todd Hidos memorable description of an oddly erotic photo his father once took of his mother that continues to haunt him.

The dilemma of the post-Magnum photojournalist usually falls into the category of the renounced picture, the result of having to choose between to be and to shoot , a choice that tragically defeated the photographer Kevin Carter. Ed Kashi encounters a terrible roadside accident in Pakistan, and is yanked out of his photographers ambivalence by his traveling companion, a filmmaker who jumps into action as an instant EMT and drags Kashi along. To be or to shoot? No question here, but Kashi regrets the missing picture as if a piece of his memory had been cut out. A very different form of the same contradiction assails Elinor Carucci after she becomes a mother of twins. Not that Sally Mann has lacked for a lifetime of material involving her own children, even as they have become adults, but for Carucci, the fundamental challenge of motherhood is to be a mother. The photographer declared war on the mother. And in those daily wars, the mother in me usually wins, she says.

Caruccis description is poignant, honest, and delicately written, just like her photographs, and it points up, for me, an undercurrent of frustration that runs beneath so many of these memories. The descriptions are so vividly renderedeach in its different waybecause they confront the fundamental inadequacy of photographs in the face of experience. As Marcel Proust understood, memory is not exclusively or even predominantly visual. It is synesthetic, a combination and even a confusion of the senses that no simple image can reach or encapsulate. A photograph can act as a spur to memory, it can yield treasures, like looking under your bed and finding the baseball card you were certain you lost. But an image stands mute before the inexpressible delicacy, horror, humor, and associative complexity of our experience. Many of the photographers offer descriptions or lists of pictures they wish they had taken, but they seem to recognize that what attracted them to those moments in the first place were often qualities or intuitions of reality that no picture could express. Doesnt language itself confront just such a limit?

That gnawing lack is precisely what drives photographers to seek more pictures and regret lost opportunitiesand poets to write more poems. As Garry Winogrand knew, the desire to photograph the whole world, all of it, is not an attempt to recover or create memories. It is a need to affirm experience as expressible, if not comprehensible, and to create an aura of talismanic protection. Sometimes to gain that affirmation, you have to give up pursuing it. As she relates here, the photographer Joni Sternbach once failed to take a picture of a young boy, the son of a surfer in California. He wouldnt cooperate, and so she gave up on the picture. Instead, he gave her a Polaroid of himself, which she still has. Had she managed to take that picture, would it have been as meaningful, as expressive of the relationship between the two people?

Perhaps only in the presence of death (odd oxymoron: can death be present?), which cannot be imaged, do we truly face the trauma of letting go, of making do with only words, or even less, with ourselves and what we carry inside.

ESSAYS

Dave Anderson

On Monday, November 3, 2008, I pulled into a poorly-lit cul-de-sac on the outskirts of Springfield, Missouri. It was dark and I was alone. I was also completely hell-bent on tracking down swing voters.

Next page