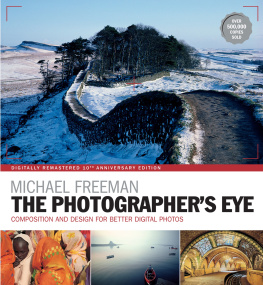

MICHAEL FREEMAN THE PHOTOGRAPHERS EYE

In his long and distinguished career, photographer and author MICHAEL FREEMAN has concentrated principally on documentary travel reportage, and has been published in dozens of major publications worldwide, including Time-Life, GEO and Smithsonian magazine, for whom he has shot dozens of feature stories across the globe over the course of a three-decade relationship. Much of his work has focused on Asia, beginning in the early days with Thailand, and expanding throughout Southeast Asia, including Cambodia, Japan and China. His most recent book of documentary reportage is Tea Horse Road, tracing the ancient trade route that began in the 7th century between southwest China and Tibet.

His numerous books teaching the craft of photography have sold over four million copies, and been translated into 27 languages. The Photographers Eye is his bestselling volume, and has become the definitive work on photographic composition and design.

MICHAEL FREEMAN THE PHOTOGRAPHERS EYE

Composition and Design for Better Digital Photos

An Hachette UK Company www.hachette.co.uk

First published in the United Kingdom in 2007 by ILEX, a division of Octopus Publishing Group Ltd Octopus Publishing Group Carmelite House 50 Victoria Embankment London, EC4Y 0DZ www.octopusbooks.co.uk

Design, layout, and text copyright Octopus Publishing Group 2007

Publisher: Roly Allen Publisher, Photo: Adam Juniper Managing Specialist Editor: Frank Gallaugher Art Director: Julie Weir Designer: Simon Goggin Design Assistant: Kate Haynes Senior Production Manager: Peter Hunt

Michael Freeman asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

ISBN 13: 978-1-78157507-9

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Printed and bound in China.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

www.hachette.co.uk

www.octopusbooks.co.uk

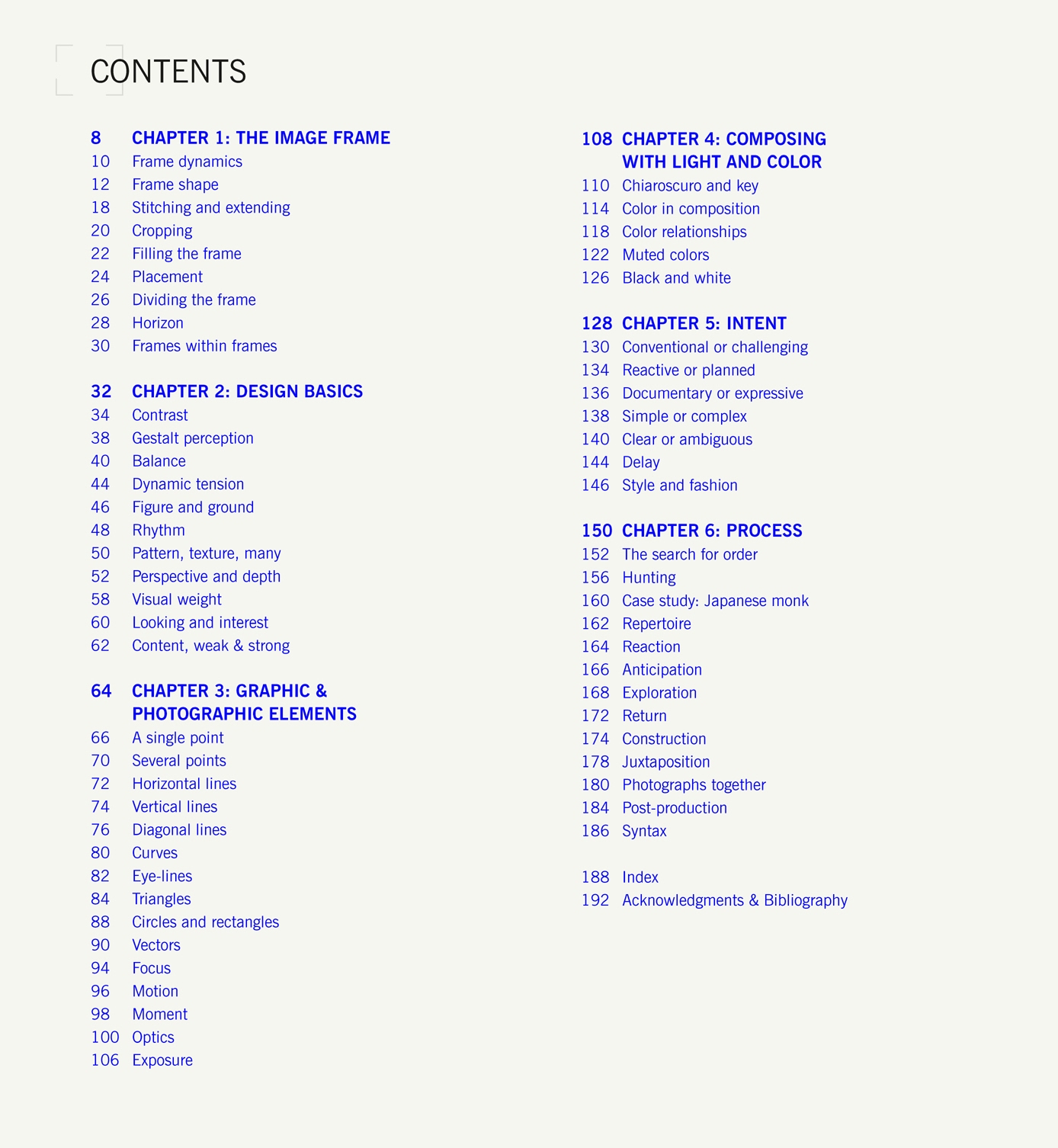

CHAPTER 3: GRAPHIC &

PHOTOGRAPHIC ELEMENTS

CHAPTER 4: COMPOSING

WITH LIGHT AND COLOR

INTRODUCTION

....how you build a picture, what a picture consists of, how shapes are related to each other, how spaces are filled, how the whole thing must have a kind of unity. PAUL STRAND

Its been ten years since the first publication of this book, and the fact that it is still going strong, in so many languages, must be some kind of vindication that the original idea had merit. It was a different idea, which doesnt sound very modest, but I mean that it was different from the other books I had already written. There were two things that I wanted to do with this book. Firstly, I wanted to put forward the view of a working editorial photographer, as I was growing tired of reading articles and books by people who stood on the sidelines and didnt seem to take it as realistically as those of us who did it for a living and for whom it filled our lives. In the introduction to the first edition I pulled a punch here. I wrote that the view of a perceptive outsider was perfectly all right, and quoted Roland Barthes who, as French philosopher and literary theorist was happy to say I could not join the troupe of those ... who deal with Photography-according-to-the-Photographer. That was a mistake on my part to be so accommodating, and Im not doing that any longer. To my mind, the first qualification for writing usefully about a creative activity is to be able to do it well yourself. Otherwise, youre in danger of writing nonsense, even if its appealing nonsense.

The second thing I wanted to do was to kick out all references to equipment and concentrate entirely on how to put an image together. That, after all, was what I spent most of my time doing, as did just about every working photographer I knew. Incredibly, despite the explosion in the popularity of photography, there was a complete dearth of writing on this. For some reason, professional photographers didnt talk about composition. Did they see it as some kind of trade secret? Was it something they genuinely didnt articulate, even to themselves? Even when they did mention it, the result wasnt usually illuminating; Hungarian photographer Andr Kertsz claimed that from the very start everything he did was absolutely perfectly composed, which smacks of hubris, but then went on to say that it wasnt to his meritI was born this way. That didnt seem like much help to anyone.

Remember that professionals, in the days when they exclusively inhabited the upper slopes of photography, thought themselves pretty special. Their magazine and ad agency employers told them and their audience so, and it made total business sense to claim the privilege of, well, a rare talent. Yes, I was party to that and we all subscribed to it. For photographers, the right stuff, if you like, was not the equipment.

It was a kind of private knowledge, not to be broadcast unless it served the photographers own publicity.

That knowledge, or, rather, the result of it, is composition. But how important is composition? From the little that was written about it at the time, youd have thought not so much. There are, after all, other ingredients that go into the making of an image. Theres the subject itself and how interesting or unusual it is. Theres the sense of timing, the quality of the light, a feeling for color or black and white. And always the equipment, starting with camera and lenses but going on from there, and a visit to any large photography convention, then and now, will definitely leave you with the impression that its the manufacturers who hold the key to excellent imagery.

As a working photographer, organizing all the stuff that has to fit in the frame was what occupied my shooting mind most of the time, and it still does. I suspected it also did for my colleagues, but we didnt talk about that kind of thing among ourselves. A more usual topic was how we managed to get to a particular subjectthe trials and triumphs of reaching a difficult location, getting an elusive person to agree to a portrait, having special access. Yet, reputations were made on what you did with the image once you got that special access or viewpoint, and how imaginative you were. What we were actually being employed for, and what would get us our next assignment, was how we individually put it all together in the frame. Picture editors and art directors valued reliability and efficiency, but they also wanted to be surprised and entertained by the images. The influential Alexey Brodovitch, who art-directed Harpers Bazaar from 1934 to 1958, had one well-known line of instruction to photographers: Astonish me!