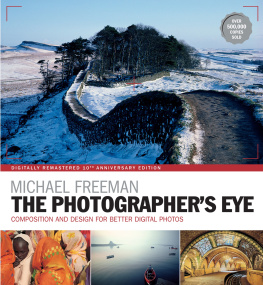

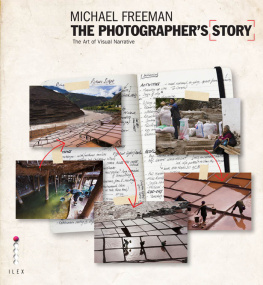

MICHAEL FREEMAN

THE PHOTOGRAPHERS STORY

The Art of Visual Narrative

I L E X

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I t took the explosion of photography into all its many modern forms to make me realize that what I had been doing most of the time was storytelling. Not all of the timethere were cover shots and single-image jobsbut mostly I did stories. At the time I didnt articulate it quite like that, nor, as I remember, did anyone else I knew. It was simply what we did, or aspired to do. Most of my life in photography has been on assignment, and most of these assignments were of a length that allowed us to move around the subject, show it in different ways, and describe it visually. Some were short, some long. They ranged from a day (not many of those) to a few months (quite a number of thosestrangely, perhaps, but a consequence of my enjoyment of long projects).

Naturally, then, this is the kind of shooting that Ive been closest to, but its only recently that Ive noticed colleagues actually saying things like Im a storyteller with a camera. Its only recently that Ive started saying this. The reason has to do with the changes in photography. Photo stories, picture stories, whatever you like to call them, were really part of magazine assignment culture. Its what magazines like Life, National Geographic, GEO, Smithsonian, Paris Match, Epoca were all about. That world isnt dead by any means, but it doesnt exercise the hold on public attention that it once did. Print, loving it though I do, is at the start of a long, slow declinewhich may sound odd, given that this book is very much print; but by slow I mean very slow. In any case, the writing is on the wall: The screen is taking over.

The result is that the old hierarchical way of doing things is disappearing, and being replaced by a more independent world in which people do photography in pretty much whatever way they likeand with so many millions at it theres a sizable support group for every interest, from iPhoneography to expressive, humanitarian, or collaborative photography. Invention continues happily, and it simply makes definition a little more necessary. One kind of photography that is redefining itself is storytelling, which for many of us is the classic, essential, and pure form of photography. Theres an entirely understandable new interest among new photographers in directing energy towards making a coherent body of work. And few things in photography are more coherent than a well executed story. This is what this book is about.

Theres a new world of self-assignment. It doesnt have the financial support that kept professional editorial photographers going, but its possible and it offers a new freedomto choose what to shoot and to do it entirely in the way you want. These may not be great days for many professional photographers, or for picture editors, but for everyone else the world of photo essays and all the other forms of narrative and storytelling through pictures is at last open to all.

PART 1

THE PHOTO ESSAY

T he term photo essay, which now seems a natural fit, was an invention not without a little pretension. It first appeared in a Life advertisement for itself in 1937, promoting the photographic story as an advanced form that went way beyond a simple collection of pictures. It claimed that the camera can picture the world as a seventeenth-century essayist or a 20th-century columnist would picture it, concluding that the sample story shown, by Alfred Eisenstaedt on Vassar, gives an impression of that college as personal and homogeneous as any thousand words by Joseph Addison. That was aiming high, indeed.

Life may have pioneered the form more single-mindedly than other magazines, but it was by no means the only vehicle for this kind of photography. In the key years of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, other illustrated magazines included Look in the US (launched 1937), Picture Post in the UK (1938), Paris Match in France (1949), and Epoca in Italy (1950). The stimulus, as well see, came first from a novel kind of fast, candid photography that new cameras made possible, and then from a handful of pioneering illustrated magazines in Germany. Publishers on both sides of the Atlantic realized by the mid-1930s that there was a huge public appetite for seeing world events in photographs. More than this, the editors saw the opportunity to create a new form of publishing over which they could have strong, but subtle, controlsequences of images that added up to much more editorially than the individual pictures. With judicious selection and layout, a group of photographs could be turned into a coherent story. This also put more control into the hands of the editorial teaman attractive idea for them, though it introduced a never-ending conflict between photographers and editors. Photographers usually want better and bigger treatment for their favorite images, while editors and designers want the photographs to serve their layouts better.

There is a subtle distinction between picture story and photo essay. In the former, photographs can be harvested from many sources, which in theory makes it possible to run a very high visual standard, and to have a visually varied effect. It also puts control firmly in the hands of the picture editor. The term photo essay, however, implies a single vision and the work of one photographer shooting in a consistent style. Variety, in the form of a compiled picture storyvery common in travel magazinescan produce a visual surfeit if not handled with some sensitivity and restraint. For example, several highly chromatic images from different hands, but shown all together, are likely to look garish.

Photographers, understandably enough, have always pushed for authorship over a photo essay. No one particularly likes sharing the stage with a competitor, and having ownership of the entire story means the possibility of some artistic success.

1. NARRATIVE

T he camera is only one tool for telling a story. Its the one that interests me most, but in order to understand what it can do its essential to look back at what is fundamental to the telling of any story, regardless of howwhether by words written or spoken, theatre, film, or still images. Or paintings on a cave wall, because arguably the first were hunting paintings in ancient caves such as at Lascaux, France (15,00010,000 BC) or the more recently discovered Chauvet cave, also in France (30,000 BC), beautifully filmed by Werner Herzog. Actually, we cannot be certain because theres no supporting evidence. Stories, icons, propitiation to the gods or spiritswho knows? In any case, storytelling runs deep in all our cultures. Its entertainment, education, and myth, and it begins with the simplest and most logical form: the narrative. Narrative means telling an account of something, how it happened.

The history of how photography got caught up in narrative goes back to the end of the 19th century, although it took until the 1930s for photo stories to become a properly developed form. Newspapers and magazines wanted imagery to accompany their text, but it was only with the invention of the half-tone process in the 1890s that they could use photographs. The half-tone plate turned a continuously-toned photo into black and white dots on a scale that could hardly be seen by a readerif you like, the earliest kind of digital imaging. The principle is the same.

Next page