MICHAEL FREEMAN

THE PHOTOGRAPHERS VISION

MICHAEL FREEMAN

THE PHOTOGRAPHERS VISION

Understanding and Appreciating Great Photography

Focal Press is an imprint of Elsevier Inc.

225 Wyman Street, Waltham

MA 02451, USA

Copyright 2011 The Ilex Press Ltd. All rights reserved

This book was conceived, designed, and produced by

Ilex Press Limited. 210 High Street, Lewes, BN7 2NS, UK

Publisher: Alastair Campbell

Creative Director: Peter Bridgewater

Associate Publisher: Adam Juniper

Managing Editors: Natalia Price-Cabrera and Zara Larcombe

Editorial Assistant: Tara Gallagher

Art Director: James Hollywell

In-house designer: Kate Haynes

Design: Simon Goggin

Picture Manager: Katie Greenwood

Picture Research: Hedda and Michael Lloyd-Roennevig

Color Origination: Ivy Press Reprographics

Digital Assistant: Emily Owen

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Permissions may be sought directly from Elseviers

Science & Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK:

Phone (+44) (0) 1865 843830; Fax (+44) (0) 1865 853333;

Alternatively visit the Science and Technology

Books website at www.elsevierdirect.com/rights for further information

Notice: No responsibility is assumed by the publisher for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions or ideas contained in the material herein

Trademarks/Registered Trademarks

Brand names mentioned in this book are protected

by their respective trademarks and are acknowledged

E-ISBN: 978-0-240-81518-3

For information on all Focal Press publications

visit our website at: www.focalpress.com

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

P hotography has come a long way in recent years. This is evident in how it is practicedwhich is to say digitally, covering more of life and experience than was possible or even desirable beforebut maybe not so evident in how it is appreciated. Cause one is that since the 1970s photography has gradually become accepted as a fully fledged form of art. This in turn has had a domino effect, in that the kind of photography never conceived as artthe majorityis now exhibited, collected and enjoyed in much the same way as other art. Cause two is that more and more people have taken up photography seriously themselves, for creative expression rather than just for family-and-friends snapshots. This makes photography subject, as no other art form, to the I could do that reaction.

You would think, wouldnt you, that with photography having become so fully embraced by everyone, that we would be taught from an early age how to follow itas a visual version of literacy? Far from it; there is not even a matching word. Although I cannot redress all of that here and now, it is worth looking at the whole spectrum of photography to show just how enriching it can be. And yet, it rarely is treated as a whole. Writing on photography tends to be partisan. Fine-art photography is usually considered in isolation, as is photojournalism, as is advertising, and so on. Personally, I dont see why this should be so, particularly now that the different genres of photography seem to be migrating. Museums now collect fashion photography, advertising uses photojournalism, landscape photography tackles social issues. Like a growing number of people, I like to think of photography as all one.

Nevertheless, an issue of identity now affects photography. It has been going on, and getting stronger, for the last three decades, and what is at stake is whether photography is rooted in capture, or in making fabulous images irrespective of whether they come from the real or from imagination. Capture is photographys natural capacity, the default if you like, with events, people, and scenes as its raw material, all happening more or less without the photographer interfering. This is the photographer as witness, as observer. Yet throughout photographys history there have been excursions into making images happen by construction, direction, creation. Tableaux telling a narrative; Surrealist experiments with process, collages, studio concoctions; still-life arrangements. Why should it be different in principle now?

What has changed has been the understanding that photography is either one thing or the other. What happened in front of the camera really happened as it seemed, or it was a different kind of photography in which things were made up. The processes of photography largely kept these two separate, with the exception of ingenious but rare attempts to alter reality. But this distinction, for many people, and perhaps already the majority, has disappeared. The two agents of change have been digital technology, naturally, but also the promotion and acceptance of concept as a valid direction for photography. There were hints of this coming from early in the twentieth century, but it was not until the 1970s that conceptual photography really got into gear.

The primacy of concept over actuality has in effect given photographers permission to make use of techniques that alter the substance of images. These techniquesdigitalcontinue to evolve, but already they are so sophisticated as to be undetectable in skilled hands. But perhaps the most important change of all is that much of the time these techniques are not operating in the context of detection. Whether a photograph is real or not is, for many people, unimportant. What is coming to count more is whether a photograph is clever enough and attractive enough. This does not please everyone, of course, but it is the reality of contemporary photography, and it calls for explanation. Or at least it calls for an attempt to integrate photography-as-illustration with photography-as-record. This is one of my aims here, within the overall framework of the capacity to read, enjoy, and have opinions about photographs in whatever form they appear.

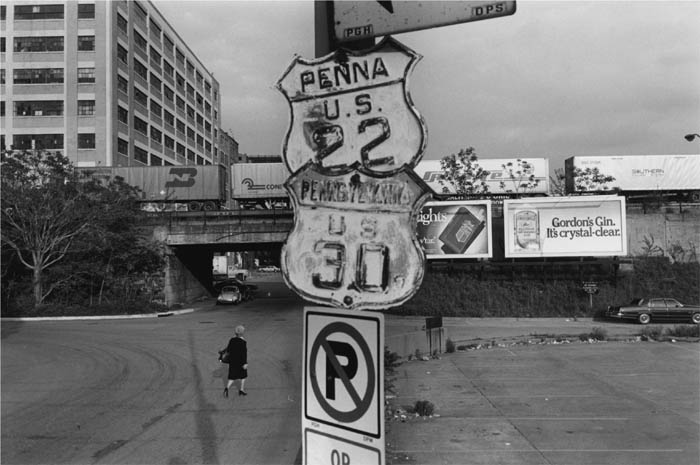

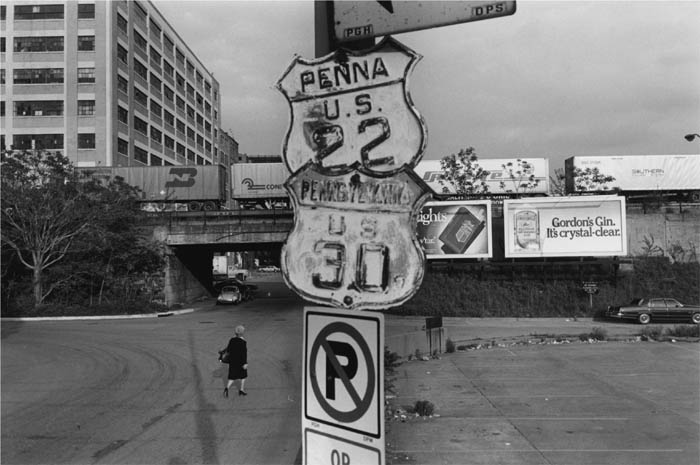

Lee Friedlander, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Pittsburg, PA ca. 19791980, by Lee Friedlander

PART 1

A MOMENTARY ART

N ow that digital photography can be processed and altered to make it look more like an illustration, and now that contemporary art is at liberty to use photography as a starting point rather than just an end-product, it might be useful to get clear in our minds what is unique about a photograph. And right here at the start its worth addressing the now-familiar concern about what can be done to a photograph digitally, in post-production, to alter it. The problem for many people is that the photograph may lose its legitimacy. Another is that perhaps it in some way is no longer a photograph, but a different form of image. This is a big debate, but for the purposes of this book I take the following, possibly simplistic view: there is nothing inherently right or wrong about digitally enhancing and manipulating a photographjust as long as no one is pretending its not happening.