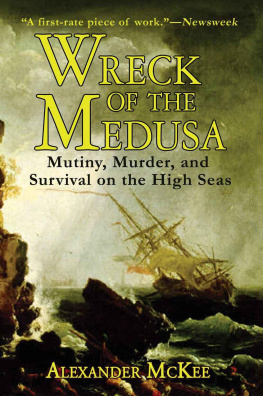

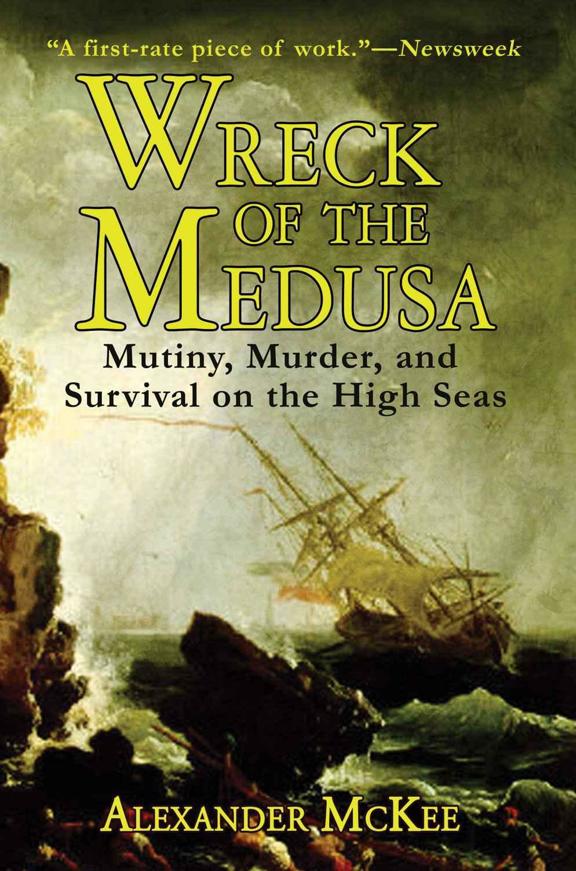

PRAISE FOR WRECK OF THE MEDUSA

[McKees] terse account of the original disaster opens out into a study of the ensuing cover-up and widening political scandal, which deeply embarrassed the French government.... Instead of exploiting the Medusa episode as a unique horror story, McKee searches out the paradigmatic elements of human behavior under stress. This is a first-rate piece of work.

Newsmeek

A weird and tragic narrative ... a spellbinding human drama that made its mark on history and art ... haunting.

Publishers Weekly

Well-told.... The real horror comes in reading the lurid details of what the author calls ... the most horrible sea tragedy of the century, possibly the most terrible that has ever taken place ... It is also instructive on the seemingly eternal propensity of man to be inhumane to his fellows.

Business Week

An epic of horror at sea.... McKee talks of cannibalism in some survival epics of this century, but if anything makes that soccer teams ordeal in the Andes seem tame, this story does.

Chicago Daily News

An admirable addition to the literature of survival.

Kansas City Star

Wreck Of The Medusa

Mutiny, Murder, and Survival on the High Seas

Alexander McKee

Copyright 1975, 2007 by Alexander McKee

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to: Skyhorse Publishing, 555 Eighth Avenue, Suite 903, New York, NY 10018.

Reprinted by arrangement with Signet, a member of Penguin Group (USA)

Inc., from WRECK OF THE MEDUSA by Alexander McKee.

www.skyhorsepublishing.com

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McKee, Alexander, 1918

[Death raft]

Wreck of the Medusa : mutiny, murder, and survival on the high seas /Alexander

McKee.

p. cm.

Originally published under title: Death raft. New York : Scribner, 1976,

c1975.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

9781602391864

ISBN-10: 1-60239-186-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Miduse (Ship) 2. ShipwrecksSenegal. I. Title.

G530.M5M32 2007

910.916375dc22

2007013433

Printed in Canada

LANDLOCKED

June, 1816

T HE girl who ran impulsively into the fields to gather blooms was saying goodbye to France. Picking a few of the red poppies and the blue cornflowers, she hurried back to join her family on the road, overcome by a feeling of sadness. Perhaps it was only a brief homesickness, but afterwards she thought it might have been premonition. Like many others making their way towards Rochefort that day, she was destined to witness the most horrible sea tragedy of the century, possibly the most terrible that has ever been enacted.

It was June 12, 1816, less than a year after the final downfall of Napoleon Bonaparte at Waterloo. It is not fanciful to link the Medusa disaster with that critical moment when the Guard recoiled and the British bayonets began to move forward, the flanking Prussians driving deep into the ruined French Army.

The fate of the Medusa, both her original mission and its terrible end, flowed as a direct consequence. That French power which had dominated Europe for twenty years had been humbled. That monarchy which France had twice rejected was once more imposed upon her by victorious foes.

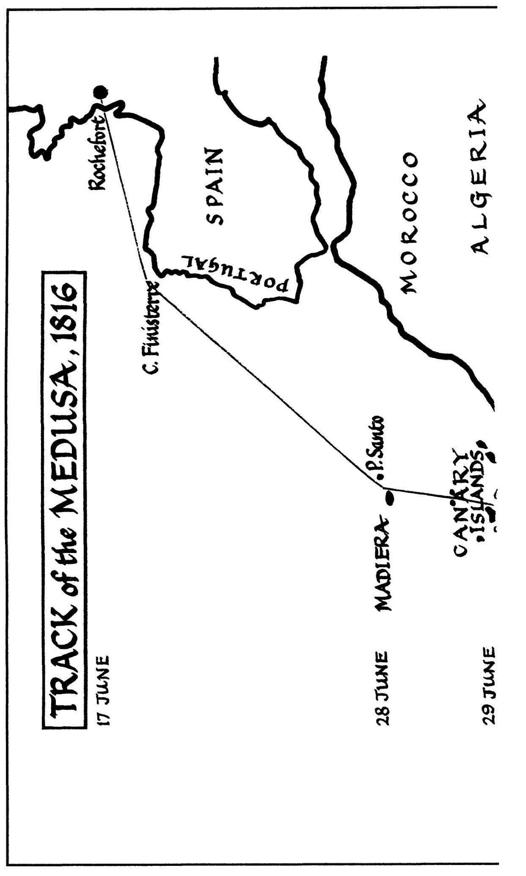

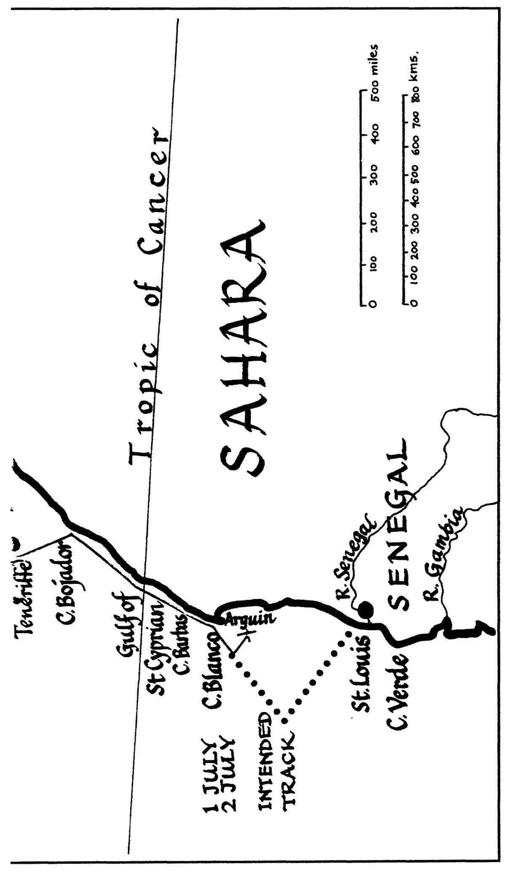

One of those enemies had returned to the restored monarchy what it had taken from the deposed Emperor. The French colony of Senegal in West Africa was to be handed back by its English captors as part of the peace settlement. And the mission to be led by the Medusa was that of re-establishing a French garrison and a French administration on that fly-blown fever coast, still largely unexplored.

Charlotte-Adlade Picard, the girl who had so impulsively picked the flowers, was one of the 365 passengers to be embarked in a four-ship convoy consisting of the frigate Medusa, the corvette Echo , the transport Loire and the brig Argus. Soldiers of a low-grade battalion under an elderly Lieutenant-Colonel formed the bulk of the passengers, but there were also engineers, accountants, hospital staff, explorers, bakers, schoolmasters and a solitary gardener. Some had been able to bring their families with them, so that there were twenty-one women and eight children among a largely male throng.

Charlotte was one of about 240 people destined to take passage in the Medusa, the flagship of the little fleet. With her crew of 160, a total of four hundred men, women and children were crammed into her wooden hull. One hundred and forty nine of them were destined never to reach Africa. Of those who did, some did not long survive the terrible ordeal they had undergone.

The girl was on the passenger list, not in her own right, but as the eldest daughter of the official intended to become the new public notary of St. Louis, the capital of the colony. She loved him dearly, although he was inclined to be outspokenly critical. M. Picard had great responsibilities already, for he had married a second time. Apart from the two grown-up daughters from his earlier marriage, he was accompanied by his second wife and their much younger children, Laura, Charles and Gustavus. Laura was only six years old while the youngest child was still a baby. He had taken under his care as well a five-year-old boy, Alphonse Fleury, who was Charlottes cousin but now an orphan. In any emergency this large family would be peculiarly vulnerable.

Their journey to Rochefort was leisurely, almost a seaside holiday for the children. They found that the town lay on the river Charente, four leagues from the wide roadstead off the isle of Aix where the ships were waiting. First they had to board a boat to take them down the winding river towards the sea. And then contrary winds delayed this craft so much that it was not until the next day that they approached the bulk of the Medusa, which was to be their home for the next few weeks. The journey might take a month, they thought. But it was exciting for the children, who had never seen a ship this close. Only their father, an old colonial hand who had been working a plantation in Senegal when the English took over, had been to sea before.

Charlotte-Adlade, a girl of good education steeped in the mystique of fashionable Paris, found provincial Rochefort monotonous and boring. Clearly, it was an important naval arsenal but the Medusa herself conveyed no warlike impression. To her, the frigate was just a great hulk of wood. Not for the first time, the first impressions of Miss Picard were to prove absolutely correct.

The Medusa had been a warship until recently and had carried a battery of forty-four (mostly eighteenpounder) guns almost entirely on one deck. But she was far from being a battleship, for they had superimposed tiers of guns on two, three or even four decks; and most of those guns were of much heavier metal than the Medusa could mount. She was a long, low ship, lightly built; in modern terms a cruiser, designed for scouting, message-carrying, patrol and convoy duties.