AUTHORS NOTE

THIS IS A true story. Evidence of 55 witnesses has been taken from the Marine Court of Enquiry held in March and April, 1918, and in private interviews with ve of the survivors.

Information was also collected from the les of the Daily News, the Evening Telegram, the Evening Advocate, and the Daily Star of St. Johns, the Newfoundland Archives, and the Department of Justice. Other sources include the Meteorological Branch of the Department of Transport; Richard Nelis, Meteorologist; C. F. Rowe, Meteorologist.

The following people provided details in interviews taped in 1972, 1973, and 1975: Captain Tom Goodyear, Ron Young, Alex Ledingham, Mrs. Michael McDonald, (nee Kitty Cantwell); Mrs. Philip Jackman, Captain Eugene Burden, Jim Myrick, R. A. (Dick) Harvey, the Herbert Taylor family, St. Johns; and Dave Grifths, Long Harbour, Placentia Bay; John Metcalfe, Topsail, Conception Bay; Samuel Cooper, Fort Lauderdale, Florida. The story of Mrs. Henry Kraph, (nee Minnie Denief), Brooklyn, N. Y., was compiled through letters to the author in 1963. Burnham Gill, Len Murphy, John Doyle, the George Crocker family, the Billy Guzzwell family, St. Johns; the Gregory Maloney family, the James Crockwell family, Bay Bulls, also provided color stories.

For vital assistance in other ways, the author thanks William and Daphne Rolls, Traytown, Bonavista Bay; Alma King, St. Johns; and Laurie and Billie Brown, Clarenville, Trinity Bay.

C. B. St. Johns, Newfoundland.

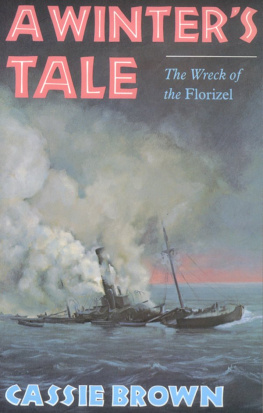

ONWARD SHE CAME, pitching and rolling wildly through the sleet-ridden blackness of night. Great seas rose up around her, hurled their smoking crests upon her deck in drenching sheets of icy spray. She heeled viciously to port and back to starboard so that all was chaos in her belly.

But she was a sturdy ship. She had shown her mettle during worse storms in the North Atlantic, and she shook off the heavy seas, smacked them resoundingly, her at-bottomed bow riding easily over them.

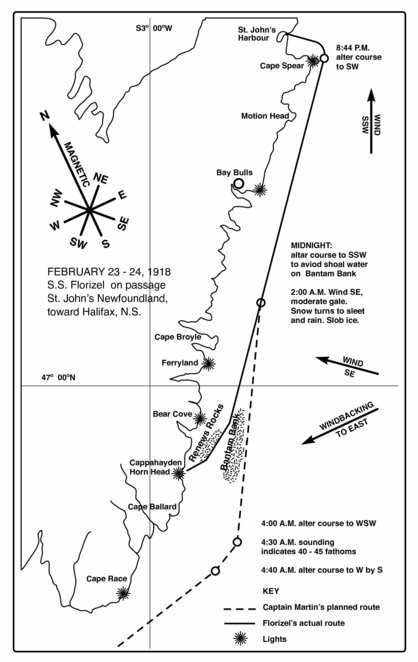

On the bridge an order was given, the course altered, and her bow swung landward. Bounding through the furious seas, the S. S. Florizel struck Horn Head Point off Cappahayden on the southeast coast of Newfoundland. Impaled on the rocks with her back broken, the bottom torn out of her, the ship began to disintegrate while her 78 passengers and 60 crew members fought for their lives. Ninety-four died.

Exactly what happened on the Florizel throughout the night of February 23-24, 1918, was to remain a mystery for more than half a century. This book tells the story of that fateful night.

FATE, THE weaver, selected with innite patience and delicacy a thread here, a thread there, uniting the various strands of life into a pattern of disaster. One hundred and thirty-eight souls would be tried and tested by the terrible destiny that awaited them. Others would be discarded before the design was complete only later would they know that Fate spared them.

The time was February, 1918. World War I was in its fourth year but Armistice was still nine months away. Urgent pleadings from Great Britain were producing a steady trickle of young men from the bays and coves around Newfoundland, despite the fact that most of her own volunteer regiment had been slaughtered like sacricial lambs at infamous Beaumont Hamel, July 1, 1916. Some of these volunteers would be chosen to play a role in this disaster.

The rendezvous was Newfoundland, that craggy sentinel of the western world. Geographically, the island lay at the tail end of the Caribbean storm path. Moist tropical winds owing northward grew rough and troublesome when they collided with the dry, cold air of the north, increasing in strength and boisterousness so that by the time they reached Newfoundland they had developed into full-blown storms with furious winds, rain, sleet, and snow. This winter there had been little reprieve from storms that wracked the island. In addition, the Polar Current nudged rocky shores with the ice pack and beleaguered the island for long, harsh weeks. Shifting winds, tides, and currents frequently caused the ice pack to squeeze and crush ships like matchwood; shipping lanes around the coast had to be navigated with extreme caution.

The victim chosen for this experience was the S. S. Florizel, of the prestigious Bowrings Red Cross Line, a large, sturdy ship of 3,081 tons gross weight, 305 feet in length with a 42-foot beam. She had four decks, four holds, and accommodations for 145 rst-class and 36 second-class passengers. She was splendidly furnished, richly carpeted, upholstered in plush, nished in oak and mahogany and costly green tapestry. Sea voyages on Bowrings Red Cross Line were popular with the traveling public. The food was outstanding, and the crew members appeared to be a close-knit family unit, radiating warmth, friendliness, and concern for the creature comforts of the passengers. A special feature was her automatic whistle, which could give eight long blasts a minute, and it was of great service when the steamer was making Long Island Sound or the Newfoundland coast both equally infamous for their fog.

Built primarily as a passenger liner, she was designed, it was said, like a codsh to cope with ice because she was used as a sealing ship in the spring of each year. She was also one of the worlds rst eet of icebreakers. She had a triple-expansion engine with cylinders of 24 inches, 40 inches, and 64 inches diameter, and a 42-inch stroke and 180 pounds pressure fed by three boilers. Her bunker capacity was 450 tons small by todays standards, but in 1909 she was the pride of Bowrings eet.

The yearly trips to the iceelds for the slaughter of seals were by far her most lucrative ventures. Her trip to the ice in 1910 netted her a record-breaking 49,000 seal pelts. During the seal hunt rough boards protected the decks from the sealers hobnailed boots, and her elegant saloons and staterooms were locked against invasion by the seal hunters who lived in her cargo holds.

Because of the war she had not gone to the seal hunt since 1915, but she had crossed the Atlantic several times with volunteers for the slaughter that was taking place in Europe. The Florizels main function, however, was the St. Johns Halifax

New York run, with the odd Caribbean cruise thrown in. The agents who booked passengers and cargo were Harvey and Company, Ltd., a large and prestigious rm.

The S. S. Florizel was overdue on her return trip from New York and Halifax. Stormy seas had forced her to run at reduced speed throughout most of the voyage, putting her a day behind schedule.

In spite of the rough weather, this particular trip was an exciting one. Among the passengers was the shipwrecked crew of the vessel Lottie Silver, whose seamen had gripping tales to tell of many near-scrapes with death aboard a derelict vessel battered by savage seas.

Listening to these stories were two young New York doctors named Knowlton and Bartecou. They were going to the iceelds in March; Knowlton would make the trip with Captain William Winsor in the Thetis