To Peter J. Connolly, Joseph E. Connolly, John Christian Schulte, and

all those who wore the American uniform during the Great War. And in

memory of Dennis Hernon.

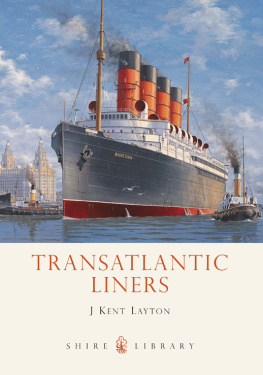

T HE LARGEST, MOST luxurious ocean liner afloat was two days out of New York and steaming to the southwest at a steady twenty knots. It was July 28, 1914, and the SS Vaterland, Germanys newest superliner, was making her fourth round-trip from Hamburg, carrying 720 first-class passengers and another 1,200 in steerage, most of them German and eastern European immigrants on their way to the New World. After encountering icebergs on her maiden voyage two months earlier, the giant ship had taken a more southerly route across the North Atlantic on this trip. Icebergs were the terror of the sea. Barely two years earlier, on April 15, 1912, the Titanic had sunk within two short hours of ramming a floating mountain of ice in a disaster that claimed the lives of all but 705 of the 2,228 passengers and crew.

The German owners of the Vaterland, which set a new standard for luxury and size after the loss of the great White Star liner, were taking no chances. The Vaterland was equipped with one of the largest spotlights ever made, a six-foot-wide, 34,000-candle monster that could bore two miles into the darkness, its bright shaft of light probing and sweeping the surface of the water for these drifting ship killers.

But it was late in the iceberg-calving season, and the ship had encountered no such dangers since steaming out of Hamburg three days earlier. In fact, it had just finished another remarkable run, covering 540 miles in one day at an average speed of nearly twenty-two knots. The seas were glass smooth, the wake a white furrow trailing out a mile to the stern. Passengers by the hundreds, many decked out in upper-class finerythe latest summer seersucker, silk, or light tweedsstrolled the enclosed promenade reserved for them, or lounged on canvas-backed deck chairs. Newsboy-style caps and straw boaters were plentiful. The ship was designed to minimize rolling, the prime cause of seasickness, but with the ocean so calm, few such cases had been reported.

While the gravest questions of war and peace were casting disturbing shadows across the European landscape, aboard the Vaterland, the pride of Germany and the flagship of the Hamburg-American Line, the mood was far from glum. The world had never seen a luxury ship built on the scale of the Vaterland, at 950 feet the largest vessel afloat, nearly 300 feet longer than the mightiest English or American dreadnought, and 67 feet longer than the Titanic. It had eleven decks and soared twelve stories above sea level, with the bridge nearly ninety feet above the water.

The liners distinctiveness started with her three canary-yellow sixty-four-foot-tall funnels and continued far below deck, where forty-eight coal-fed boilers turned four propellers that were each eighteen feet high. The real beauty, style, and lavishness of the ship were displayed throughout the eight main passenger decks. First-class passengers such as Paul J. Rainey, an American multi-millionaire playboy and African big-game hunter, the German ambassador Count Heinrich von Bernstorff, and Adolph S. Ochs of the New York Times enjoyed luxurious trappings that rivaled the worlds best hotels. The two imperial suites on C deck each had nine rooms complete with a private patio overlooking the ocean; one of the suites included an upright piano with inlaid wood specially designed for the kaiser. The sumptuous first-class staterooms had marble washstands and private baths with toilets, features unheard of on other liners.

The seven hundred first-class passengers enjoyed the run of nearly 60 percent of the Vaterlands public spaces. The wealthiest among them had entre to the opulent Ritz-Carlton restaurant and the equally regal Palm Court. Located on B deck, the Ritz-Carlton was the elegant twin of the New York restaurant by the same name. With fluted Doric columns and a wall of colored-glass windows that soared two decks high, it was operated by the Swiss hotelier Csar Ritz and decorated with walnut paneling. A single days menu, under the title Bold Dishes, included: Pork Chops in Jelly; Duck a la Montmorency; Leg of Pork with Cold Slaw; Beefsteak Tartare; Roast beef; Roast veal; Smoked Ox Tongue; Smoked Ham; Boiled Ham; Various kinds sausages. The magnificent Palm Court, also called the Winter Garden, was located a mere six steps from the Ritz-Carlton and featured mature palm trees, a twenty-one-foot-high ceiling, gilt latticework, and oils by Giovanna Battista Pittoni, a seventeenth-century Venetian painter known for his florid rococo style.

The other first-class travelers, for whom dinner jackets, tuxedos, and formal gowns were de rigueur, ate in the dining saloon, which rose to a twenty-eight-foot-high cupola and included a balcony for the orchestra and two private dining rooms. A triple-tiered central staircase allowed guests to make a grand entrance as they descended from the upper deck. Four enormous oil paintings depicting scenes from the myth of Pandora by the seventeenth-century Flemish master Gerard de Lairesse and donated by the kaiser decorated the social hall, where guests gathered to dance to Strauss or the latest jazz. The kaiser had also donated a bronze statue of Marie Antoinette cast by Houdon in 1780 and a marble bust of himself with helmet and mounted hawk, which stood outside the hall.

The library on B deck featured a castle-size fireplace. The smoking room on A deck had a massive three-paneled stained glass window overlooking the bow, oak wainscoting, a beamed ceiling, and another impressive fireplace made of white stone with a wooden mantel. Paintings of Bismarck, members of German and English royalty, and other notables, including Washington and Lincoln, were mounted in the Ritz-Carlton and the Palm Room and in the other public spaces. The frescoed swimming pool was a must-see. Depicting scenes from Pompeii, it was dominated by a black marble statue of a winged, phallic cherub that sent long arcs of water splashing into the pool.

Second- and third-class accommodations included berths for up to 1,600 passengers. These guests werent allowed in the swimming pool, but had their own elevator along with a gymnasium, dining saloon, and smoking room.

The steerage staterooms on G, H, and I decks were located just above and below the waterline and accommodated anywhere from four to eight people, who slept on bunk beds. Crammed into the bow section was enough space in steerage for 1,700 passengers, who shared a dining room on F deck outfitted with long wooden tables and bench seating. Although the space lacked the embroidered linens, sterling silver, Limoges china, and fresh flowers that graced dining tables in first class, it was staffed by attentive waiters in uniform, and for most of the immigrant passengers, many on their way to New York and points beyond, steerage must have seemed heaven sent. They even had a spacious area where they could do their wash in large enameled tubs with hot and cold water. Many of these passengers were couples with young children who were bundled in thick wool clothing and caps even in the bright July sunshine. Deck space was reserved for them in a long, narrow area just forward of the bridge, where they could enjoy the sea air, read, or play shuffleboard and other games. Steerage was a major moneymaker for the owners, who charged $29.50 for passengers traveling from Hamburg to New York. For reasons that arent clear, Russians were required to pay $1.25 extra.

All told, the ship had room for just over 4,000 passengers and a crew of 1,200. After the Titanic disaster, the German line made sure the Vaterland had enough lifeboats to carry 5,300 people. As another consequence of that deadly sinking, the