CONTENTS

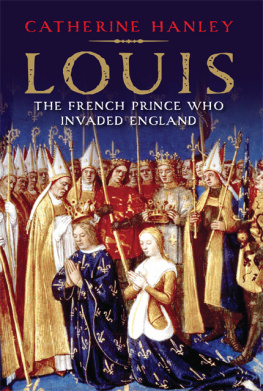

Every schoolchild knows that the last military invasion of Britain occurred in 1066. The arrow that Harold, the last English king, took in the eye (possibly) was certainly a pivotal moment in the history of these isles. But other invasions, two of which achieved their aims, have been erased from popular history and the nations collective memory. So too have countless raids, attacks, and attempted invasions which in scale were bigger than the Armada and posed an even greater threat than, it can be argued, Adolf Hitler. It is as if the Battle of Hastings was a foretaste of the Battle of Britain in 1940, with not much in between to worry those who stayed safe within these shores.

That is, however, belied by the numerous fortifications around our shores and ports, from round Martello towers to military canals and massive gun emplacements, some preserved in pristine condition, others mouldering brickwork buried in brambles.

This is my attempt to fill the gap in that collective memory. This is not an academic work for those, see the bibliography but it does aim to pull together in a straightforward narrative the astonishing events of almost a millennium, which have created the nation of Britain.

My thanks, as always, to my family.

crushed, imprisoned, disinherited, banished

the chronicler Odericus Vitalis

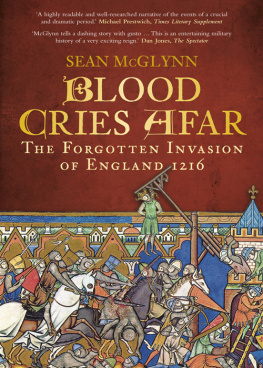

Normans preparing to invade England, Bayeux Tapestry.

Before the bloody battle on Senlac Hill and Williams conquest, invasions had been an integral part of the patchwork fabric which made Britain: Romans, Angles, Jutes, Saxons, Vikings, Danes and other Scandinavians all planted their standards and all, through assimilation, stayed to varying degrees. As the Roman Empire declined, its hold on Britain loosened. By AD 410, Roman forces had been withdrawn and small, isolated bands of migrating Germans began to invade Britain. There was no single invasion, but the Germanic tribes quickly established control over a mainland not yet a nation. Viking raiders landed near the monastery on Lindisfarne, slew its monks and looted it. Thus began more than two centuries of Viking incursions into England, which was divided into several kingdoms.

In 866, the Viking chief Ragnar Lodbrok was captured by King Aella of Northumbria and thrown into a snake pit. Ragnars enraged sons, taking advantage of Englands political instability, recruited the Great Heathen Army, which landed in Northumbria that year. York fell to the Vikings. Aella was in turn captured by the Vikings and executed. By 1000 the Vikings had overrun most of England and parts of Ireland. In Wessex, King Alfred the Great held off the Vikings during his lifetime, but the Norsemen managed to unite much of England with Norway and Denmark in the eleventh century during the reign of the Danish King Cnut.

When Cnut died he was succeeded by the Anglo-Saxon king Edward the Confessor, who reigned until his death in 1066, when he was succeeded by the powerful Earl of Wessex, Harold Godwinson. The Norwegian king Harald Hardrada invaded the North, only to be defeated with massive losses at Stamford Bridge. But William of Normandy, who also had legitimate claim to the throne, was waiting for good weather to carry his invasion fleet across the Channel.

Harold Godwinson retraced his steps south to take on the threat of the Normans, who landed at Pevensey Bay. He believed that England was now invincible, and that confidence lured him to disaster. The slaughter near Hastings dwarfed even the 901 massacre by Vikings at Maldon, or the defeat of Edmund Ironside by Cnut at Assendon in 1016. So much is common knowledge, along with the debate as to whether Harold died from an arrow in the eye or was hacked apart by Norman knights. Both, probably. But the invasion was not completed in a single battle, famous though it remains.

After the Battle of Hastings, William and his forces marched to Westminster Abbey for his coronation, taking a roundabout route via Romney, Dover, Canterbury, Surrey and Berkshire. From the foundation of the Cinque Ports in 1050, Dover had dominated and it became Williams prime target. William of Poitiers wrote:

Then he marched to Dover, which had been reported impregnable and held by a large force. The English, stricken with fear at his approach, had confidence neither in their ramparts nor in the numbers of their troops While the inhabitants were preparing to surrender unconditionally, [the Normans], greedy for money, set the castle on fire and the great part of it was soon enveloped in flames [William then paid for the repair and] having taken possession of the castle, the Duke spent eight days adding new fortifications to it.

The Castle was first built entirely out of clay. It collapsed to the ground and the clay was then used as the flooring for many of the ground-floor rooms. William, variously described by chroniclers as cruel, greedy and devoutly pious, replaced the Saxon hierarchy or establishment with his own, amalgamated the Church, imposed new taxation and his own stringent version of the feudal system, and above all wiped out resistance. The chronicler Odericus Vitalis wrote: The native inhabitants were crushed, imprisoned, disinherited, banished and scattered beyond the limits of their own country, while his own vassals were exalted to wealth and honours and raised to all its offices.

After 1066 foreign incursions, real or threatened, continued until William re-forged his realm, bending it to his own will. But it was a drawn-out business. His iron heel quickly assured his rule in London and the South, but rebellions popped up across his new realm, often aided by overseas forces. He brutally subdued the populations of Yorkshire, Nottingham and Warwick, and repeated the exercise in Somerset, Dorset and the West Midlands.

On the Welsh border, Norman earls whose families had settled in the area during the reign of the Confessor snatched lands held by Edric the Wild. There was open warfare. Edric, in alliance with the Welsh princes Bleyn and Rhiwallon, devastated Herefordshire and eventually sacked Hereford itself. They withdrew back into the hills, knowing full well that William would seek vengeance.

King Harolds mother, Gytha, encouraged the people of Devon to rise up and William only subdued the county after Exeter fell. The other main claimant to the English throne, Edgar eling, grandson of Edmund Ironside, issued a call to arms from his bolthole in Scotland. Later in the year, the men of Dover invited Eustace of Boulogne to help them in their insurrection. This uprising was soon put down with extreme prejudice. But it was in the North that William suffered the greatest defiance. William took his army to crush revolt in Northumberland. The rebels quickly either submitted or fled into Scotland to join the other refugees there in the face of Norman military might.

In the autumn, cousins of Edgar sailed to the Norse-held east coast of Ireland, picked up recruits and raided the West Country, where the Celtic Cornishmen joined them in arms. They plundered and ravaged the countryside so excessively, however, that eventually even the Saxon English joined with local Norman garrisons to expel them.

In 1068, King William appointed Robert de Comines as Earl of Northumberland, instead of the English Earl Morcar. The men of the county promptly killed him and massacred 900 of his men in Durham. Edgar eling travelled to York when he was met by the Northumbrians. William moved up fast from the south and surprised the rebels. Hundreds were slain and the city torched. The conqueror made York his base of operations in the North. He expropriated property and divided half amongst his Norman followers and kept half for himself. William strengthened the defences of the city and built two motte and bailey castles, one on each side of the River Ouse.