A bad earthquake at once destroys the oldest associations; the world, the very emblem of all that is solid, had moved beneath our feet like a crust over a fluid; one second of time has created in the mind a strong idea of insecurity, which hours of reflection would not have produced.

Charles Darwin, reflecting on the devastating February 20, 1835, earthquake in Concepcin, Chile

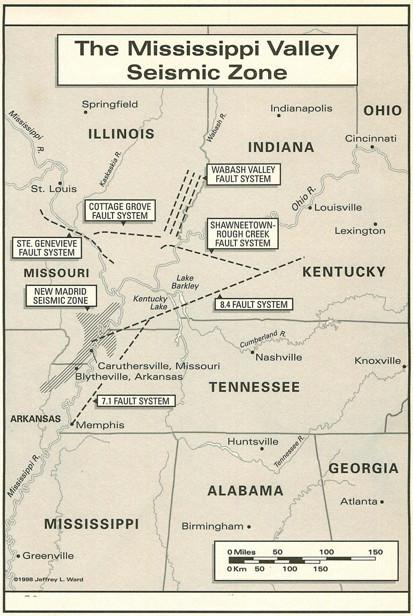

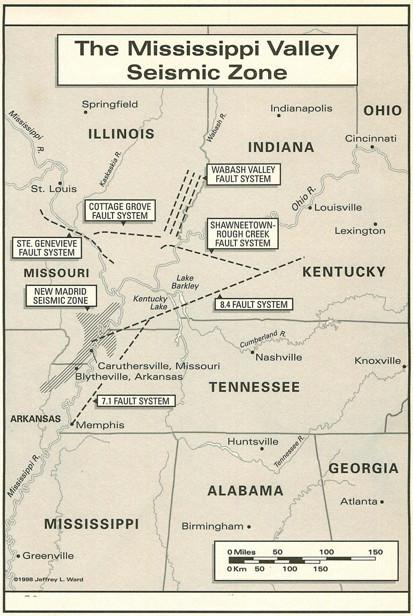

Will a catastrophic earthquake strike someday on the New Madrid Seismic Zone?

Without a doubt.

The only question is when. Experts dont expect another big one for at least a hundred years, but no one knows for sure and thats what makes seismologists and emergency planners nervous when they talk about the NMSZ.

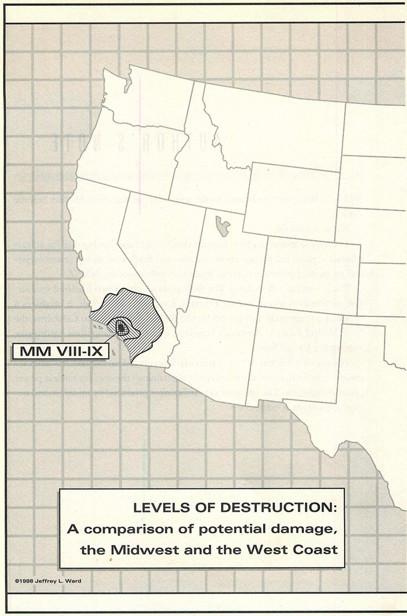

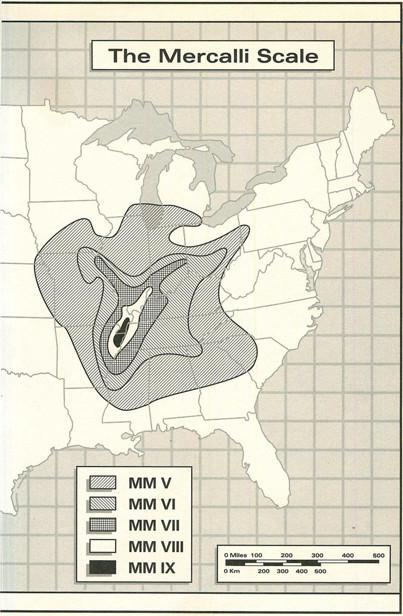

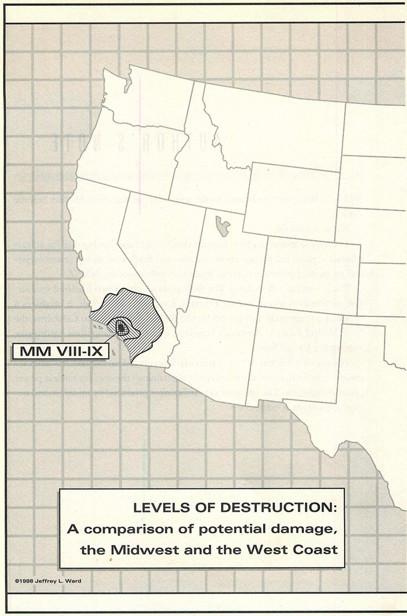

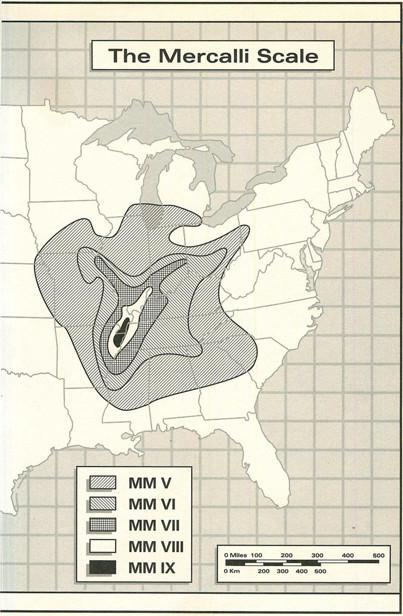

The ground is still shaking. The fault averages about two hundred measurable earthquakes a year, twenty a month. Every year and a half, it produces a shock of magnitude 4 or greater on the Richter scale. Next to California, the New Madrid Fault in Americas heartland is the most dangerous earthquake zone in the United States.

The use of a nuclear device to turn off an expected earthquake has been seriously suggested, especially as a way of destraining the sites for nuclear power plants or big dams. The literature on earthquakes produced by underground nuclear explosions is extensive.

BENTON, KENTUCKY

JANUARY 9

10:30 A.M.

JOHN ATKINS GOT OUT OF HIS MUD-CAKED GMC Jimmy and felt the wind slice through his parka. Hed pulled to the side of a country road twelve miles west of Benton, a small town in the extreme corner of southwestern Kentucky. Cornfields lined both sides of the single-lane gravel road. Left standing after the fall harvest, the dry stalks were as tall as a man.

Atkins was lost. Any other time it might have amused the seismologist, whod made his reputation tracking killer earthquakes around the globe and had never gotten lost. But not when he was running late and it was his own damn fault. He knew he should have called ahead and gotten directions.

The night before, hed flown into Memphis and rented the Jimmy. Hed driven 150 miles north through Tennessee and crossed the border into Kentucky earlier that morning. Later that day, if he could get his bearings, he planned to meet his old friend Walter Jacobs, head of the Center for Earthquake Studies at the University of Memphis.

He opened a folding map hed bought at a gas station and laid it on the hood of the Jimmy, holding the corners down against the wind. The gravel road hed been following for the last four miles wasnt even on the map, and he regretted he hadnt taken the time to pick up a good topographical one before he left Memphis.

Deciding to turn around, Atkins took a final look up the road, which continued on a straight, rutted line through the wind-blown fields. There was no sign of a house, turnoff, or barn.

Refolding the map, he heard a sharp, high-pitched sound. Coming from somewhere to his right, it was faint and almost inaudible, but as he listened the noise grew louder. There seemed to be two distinct sounds mixed together: one, soft like wind blowing through dried leaves; the other more shrill.

Atkins strained to hear. It sounded like insects, thousands of them. Maybe locusts. But not in the dead of winter. That was impossible.

Whatever was making the noise was moving fast. In a matter of seconds, the sound had increased in intensity.

Atkins climbed up on the hood of the Jimmy to try to get a better look. He didnt see anything unusual. The cornfields stretched for acres in either direction. The wind stung his eyes. He rubbed them and stared out across the fields, which gently sloped down from low, gray hills. The tops of the cornstalks rippled in the wind.

Difficult to pinpoint, the sounds seemed almost to surround him.

Out of the corner of his eye, he thought he saw movement in the field about forty yards from where he was parked. He stepped up on the roof of the Jimmy. Standing there, he watched in amazement as the tawny stalks of corn fell over. They were making the rustling sound hed noticed. It was as if a huge blade were slashing through them at ground level.

Something was cutting a ragged swath ten feet wide through the middle of the field. And it was headed in his direction.

Transfixed, Atkins watched as row after row of cornstalks pitched forward.

Atkins thought about insects or birds. Thousands of small birds, chirping loudly. Maybe starlings. Hed heard flocks of starlings before. Their noisy chittering was similar to what he was hearing. And they liked to settle in cornfields and gorge themselves.

But how could birds make the stalks fall over in neat rows like that? It was baffling.

The moving furrow was thirty yards away and looked like it would cross the road directly in front of the Jimmy.

The wind shifted and the noise suddenly became clearer, more sharply focused. Atkins still couldnt place it, but decided to get back into the Jimmy and start the engine. He didnt want to meet whatever was going through that cornfield without some protection.

Atkins climbed down on the hood and jumped to the ground just as a gray rat ran out of the field and across the road.

It was the biggest field rat hed ever seen. Two more rats charged across five feet in front of the Jimmy, disappearing in the cornstalks on the other side. Three others followed. All he saw were gray streaks.

Atkins watched, his revulsion mixed with fascination. During a trip to India a few years earlier, a rat had bitten him when he reached under a bed to find his shoes. It was a nasty wound that had become infected. Hed almost come down with tetanus.

More rats fled the cornfield in a panic. Something had to be chasing them.

But what?

The rodents exploded out into the open, four and five at a time. One stopped in the middle of the road and stood on his hind legs. Sniffing the air, its long whiskers twitching, the rat stared at Atkins for a moment before it raced off.

The noise had built to a steady, ear-splitting sound of alarm. As Atkins watched, a row of cornstalks ten feet wide fell forward into the road. A gray, undulating wave of rats swept into view.

Hundreds of them, thousands.

The hairs on his neck standing on end, Atkins ran to the door of the Jimmy. He was stepping on rats, kicking them out of the way, crushing them. One hit him in the chest and hung on, clutching the front of his parka with its claws. He batted it away with a gloved fist. Moving for the door, he tripped and almost fell, just managing to grab the side-view mirror.

The rats kept hurtling out of the cornfield. Atkins opened the door, still kicking at them. They were scurrying under the Jimmy, a dense, squealing mass with long, obscene tails. Atkins jumped inside on the drivers side, killing a rat in the doorjamb when he slammed it shut.

Two rats leaped inside before he got the door closed. Atkins kicked furiously at the floorboards, killing one with his foot. Again and again, he smashed at the other with his fists until he finally broke its neck. Something hit the windshield. First one, then another rat slammed into the glass. Pushed along by the frantic hordes still behind them, they were trying to leap over the obstruction in their path.

Horrified, Atkins sat in the Jimmy as the rats swarmed over it, covering the hood like a moving, gray blanket. In their frenzy, they slammed into the windshield and wiper-blades. Some were trampled by those charging behind them. Nipping and biting each other, many bled from wounds. The vehicle began to sway as waves of rats buffeted the front bumper. Atkins watched some of them scamper across the sunroof.