TRANSATLANTIC LINERS

J. Kent Layton

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

Laid up in Long Beach, California, the Queen Mary is a reminder of the glory days of the transatlantic liners. This view looks from her forecastle towards the superstructure.

Published in Great Britain in 2012 by Shire Publications Ltd, Midland House, WestWay, Botley, Oxford OX2 0PH, United Kingdom.

44-02 23rd Street, Suite 219, Long Island City, NY 11101, USA.

E-mail:

2012 J. Kent Layton.

All rights reserved. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrical, chemical, mechanical, optical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Enquiries should be addressed to the Publishers.

Every attempt has been made by the Publishers to secure the appropriate permissions for materials reproduced in this book. If there has been any oversight we will be happy to rectify the situation and a written submission should be made to the Publishers.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Shire Library no. 660. ISBN-13: 978 0 74781 087 2

PDF e-book ISBN: 978 0 74781 115 2

ePub e-book ISBN: 978 1 78200 098 3

J. Kent Layton has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this book.

Designed byTonyTruscott Designs, Sussex, UK and typeset in Perpetua and Gill Sans.

12 13 14 15 16 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

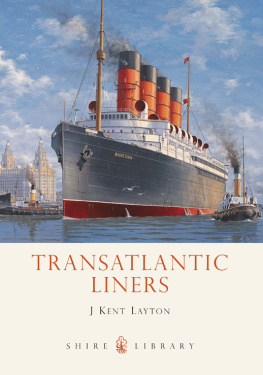

COVER IMAGE

A painting commissioned by Cunard for the Queen Mary 2, showing the Mauretania outbound from Liverpool.

(Courtesy of Cunard, with special thanks to GB Marine Art.)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank my friends and family for encouraging me to pursue a career in maritime history and to those who have contributed to my research over the years. Also particular thanks go to those who have contributed or allowed me to use illustrations for this publication, which are acknowledged as follows (referenced to page numbers):

Brown Brothers: (bottom)

All remaining images are from the authors collection.

Shire Publications. Access to this book is not digitally restricted. In return, we ask you that you use it for personal, non-commercial purposes only. Please dont upload this pdf to a peer-to-peer site, email it to everyone you know, or resell it. Shire Publications reserves all rights to its digital content and no part of these products may be copied, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise (except as permitted here), without the written permission of the publisher. Please support our continuing book publishing programme by using this pdf responsibly.

CONTENTS

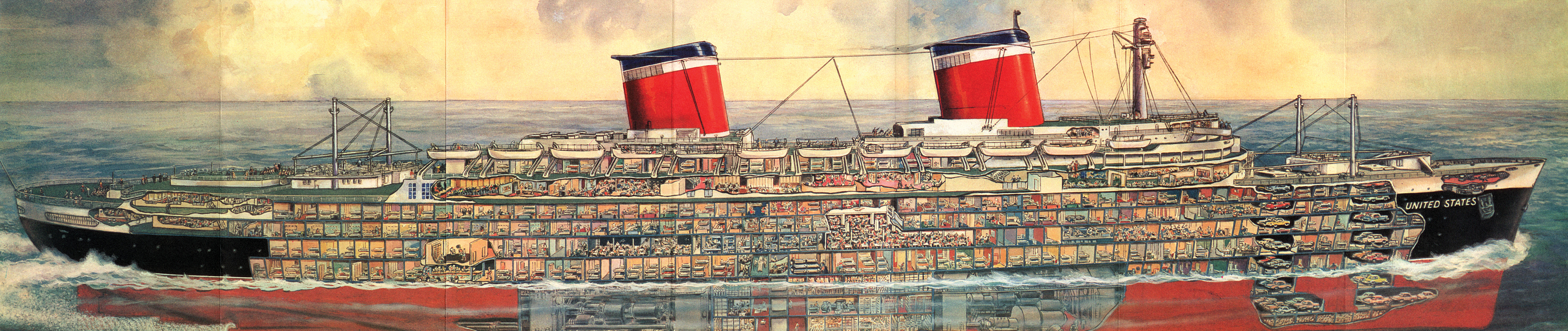

A splendid cutaway view of the United States in period publicity material.

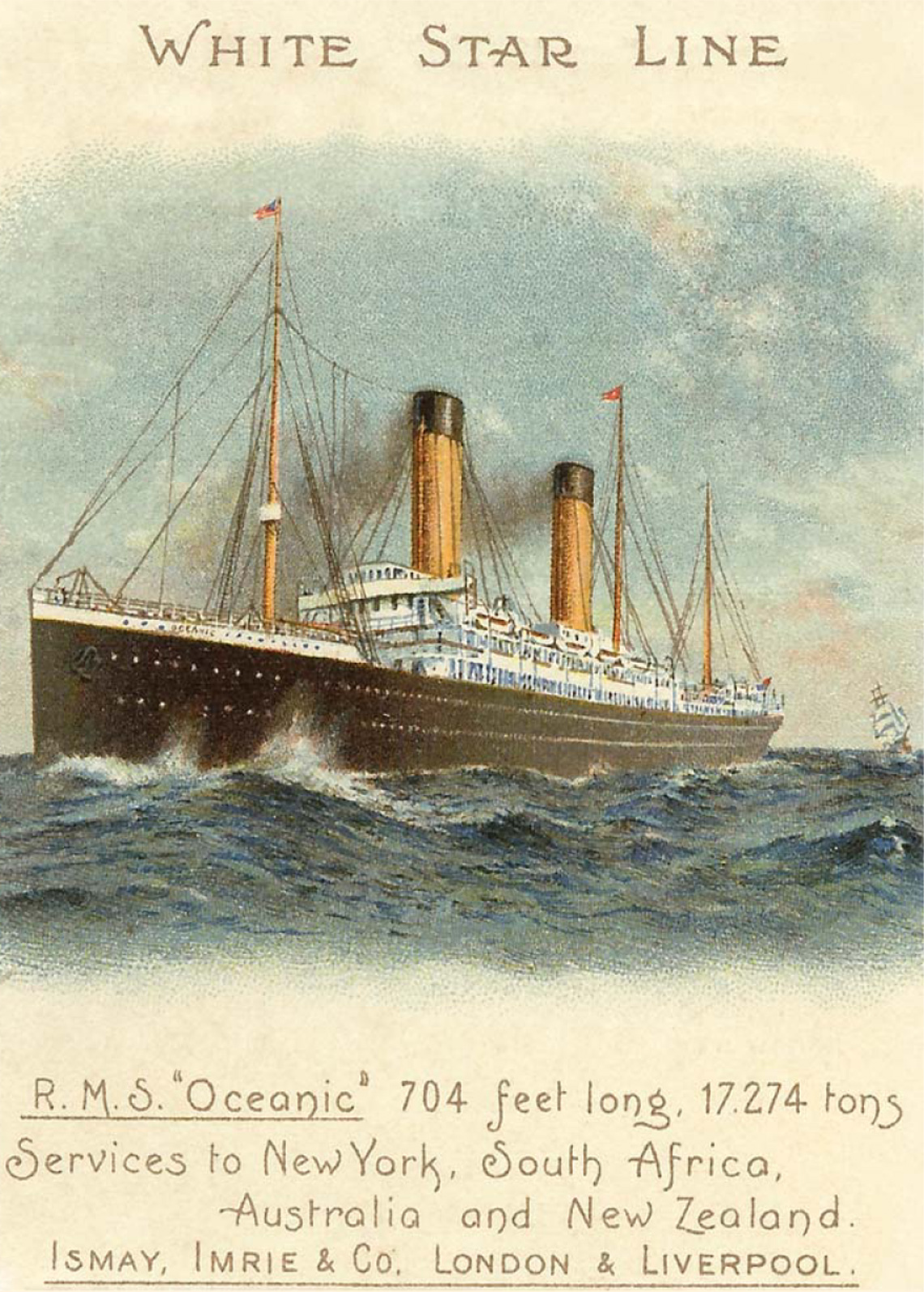

An advertisement for the White Star liner Oceanic of 1899, showing her fine lines and proud funnels.

THE EMERGENCE OF THE SUPERLINER

A S THE NINETEENTH CENTURY was drawing to a close, incredible progress had been made in the design of seagoing vessels. As that century began, ships were wooden-hulled, sail-powered craft ranging from less than a hundred tons up to several thousand tons for prestigious naval ships of the line. The speed and safety of the passage across the ocean depended greatly on prevailing winds for propulsion, and many of these craft were lost when the capricious whims of nature turned violent. Schedules were difficult to keep particularly when ships came upon doldrums. If navigators became uncertain of their location, or made even minor errors in judgement at critical moments when in the vicinity of the shore, disaster was often not far off. This was particularly true when sailing vessels found themselves too close to dangerous shorelines with the winds against them. Indeed, many vessels merrily set sail from port with cargo and passengers, and were never seen or heard of again.

As the industrial revolution began to take firm hold on land, however, it was only natural to expect that keen minds would begin to apply technology to the problems of ocean travel, and this they did. The application of steam engines and of iron, and then steel, hulls allowed ships both to abandon reliance on sails and to offer unprecedented comforts to prospective passengers. Ships grew larger and faster with astonishing speed, and competition on the North Atlantic which connected Europe and the Americas, and was thus a focal point for international trade between the worlds leading powers grew ever greater. There was also no small amount of national pride over who had the worlds largest, fastest or most luxurious ocean liners, and this further drove competition between the great steamship lines.

Despite the hazards involved, there were many reasons why people travelled across the Atlantic. Some travelled for business, some for pleasure, and others formed part of the mass migration from the Old World to the New. These passengers were divided into different categories, or classes, based on their financial and social status. Immigrants formed a large proportion of ocean-going clientele. Steamship lines provided them with simple, relatively inexpensive accommodation in the less desirable areas of their ships, and found great profits in doing so. This group comprised third class, also known as steerage in a term held over from the early days of immigrant ships. In some continental vessels, third class was subdivided again to form third class and fourth class/steerage.

Above was second class, where one found business people, teachers, students, and other middle-class people. Their accommodation was comfortable, spacious, and well thought out. First-class passenger lists, by way of comparison, included very successful businessmen, stars of the stage, heads of state and royalty, and the stratospherically wealthy. They were given the most desirable locations on the ship, and no expense was spared in giving them the most comfortable and luxurious accommodation.

Passengers in general were keen to travel on the largest, fastest and most prestigious ships. In the name of technological progress, sails had eventually given way to steam engines with screw propellers, wooden hulls to iron and then to steel, and clipper stems to knife-like vertical prows. Ships became more reliable, and were better able to withstand the navigational hazards and forces of nature that they encountered. Taking passage across the Atlantic had become less of an overtly danger-fraught ordeal and more of a routine occurrence.

Then on 14 January 1899, the next great step forward in maritime progress took to the water for the first time. Built for the White Star Line White Star and the Cunard Line held prominence as the two foremost British steamship companies this great vessel was named Oceanic