A UTHORS NOTE

All the details of this story are true. The evidence given by fifty-two witnesses has been sifted and correlated from court records. We have reproduced as faithfully as possible the dialogue as it was remembered by the men who testified, or who later recorded their recollections of that unforgettable spring. Where testimony conflicts, both sides of the story are given, but we have often had to make a judgement as to what really happened. In a few cases, judgement must still be suspended.

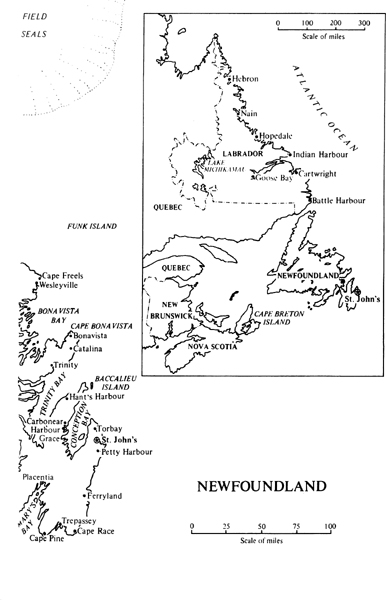

Information was collected from files of the Daily News, the Evening Telegram, the Mail and Advocate, the Newfoundland Archives, and (with the kind permission of the former Attorney General of Newfoundland, the Hon. L.R. Curtis) the law library of Confederation Building, St. Johns. Other sources include the Fisheries Research Board of Canada; the Meteorological Branch of the Department of Transport; C.F. Rowe, meteorologist; Chafes Sealing Book: John Feltham: Cooker and the F.P.U.; J.R. Smallwood: Cooker of Newfoundland, and Abram Kean: Old and Young Ahead; Bertram H. Shears.

Cecil Mouland of Hare Bay, Bonavista Bay, and John J. Howlett of The Goulds supplied many details of the story in interviews taped in 1969 and 1970.

C.B.

St. Johns

1972

F OREWORD

Every spring for more than a century Newfoundland men and boys went out in ships to the most dangerous and brutal adventure that has ever been called an industrythe seal hunt. More than a thousand of them died when their ships sank, crushed like eggshells by colliding ice-fields, or exploded, or failed to pick them up from drifting floes, when boats were driven away in blizzards, or when those on foot were caught by storms. Survivors often lost fingers or toes, or sometimes feet or legs from freezing or other injuries.

The hardships they endured were compounded by the greed of the shipowners, who refused to provide clothing or safety equipment. The men had no meals to cook or any way to cook them: for weeks and months they lived on sea biscuit and tea. Even their drinking water was polluted with blood and seal fat until it stank. They slept like cattle in ships holds without bedding. As the pelts and fat piled up, they simply lived on top of the cargo in utter filth. Injured men recovered as best they could, or died without medical help.

This book tells the story of the most appalling event in a long record of lost parties of sealers. The Newfoundland disaster, as it is called, was unique in several ways: It happened at a moment of reformWilliam Coaker, the workingmans hero of the time, was present as an observer on one of the ships to record the way the men were mistreated and the way the sealing laws were flouted by shipowners. As a result of the disaster the men rose up in revolt against feudal working conditions and against captains who valued seal pelts more than human lives; no less than two judicial enquiries sifted and recorded evidence from numerous witnesses; over it all brooded the patriarchal figure of Captain Abram Kean, the man chiefly responsible for the tragedy, and the only ice skipper ever to bring home a million seals.

A great uncle of mine, Sam Horwood, the master of a fishing schooner and as tough a man as I ever knew, was a sealer on Keans ship that spring. Like others, he tried, ineffectively, to prevent the disaster, but he did not try hard enough. I once asked my father why someone as able and experienced as Sam Horwood did not lead a mutiny, if necessary, to save the lives of the sealers.

Like all the rest of them, he was afraid of Abram Kean, my father replied. The mutinies happenedbut only after the men were already dead.

Though this book reads like a novel, it is historically accurate down to the last detail. Conversations between men on shipboard or on the ice-floes are reconstructed, word for word, from evidence given at the enquiries. Cassie Brown has done a remarkable job of research and reconstruction. She interviewed survivors at great length, studied all the written records and the meteorological and other data. The only liberty she has taken is to restore the dialect in which the men actually spoke, rather than give the correct English into which court reporters translated their speech.

This is Cassie Browns book, not mine. She did more than nine tenths of all the work on it. My contribution was limited to editorial advice, mainly to cutting and trimming the narrative from a much longer one to its present length.

D EATH ON THE I CE is the most moving story I have ever read. I am proud to have had some small part in preparing it for publication.

HAROLD HORWOOD

TORONTO, 1972

To the Halifax Chronicle it was just a routine news item in the issue of May 11, 1914:

CHARLOTTETOWN, May 10On Sunday morning a lobster fisherman employed at S.C. Clarkes factory at Bloomington Point on the north side of the island found the body of a man frozen fast in a floating ice cake about half a mile from land. Having nothing in his boat with which to cut the body loose from the ice, the fisherman had to abandon it; a heavy gale coming up, the boat had to make for land, and could not return to the body, which was carried out to sea. The dead man was evidently a sailor or fisherman judging by his clothing, and it is thought to be one of the Newfoundland sealers

On a black midnight, March 9, 1914, the S.S. Newfoundland ground her way through the loose ice of St. Johns harbour heading for The Narrows and the ice-fields beyond. It was the old wooden steamers forty-second year, the fourth as her captain at the seal hunt for twenty-nine-year-old Westbury Kean, the youngest son of the all-powerful Captain Abram Kean, unchallenged admiral of the sealing fleet.

The captain was young, but many of his crew were much younger. The dangers of the seal hunt, a spring ritual in which men slew and were slain, had made it the supreme test of manhood for Newfoundland boys. Lads of sixteen clamoured for berths to the ice and even fifteen-year-olds made the trip as stowaways.

What, Reuben, ye goin tthe ice again? joshed a sealer who had met him on the docks. I tought yed give up swilin fer good.

I come, Reuben stated soberly, to look out fer Albert John, he were that set on swilin.

The boy had got his ticket only because of his fathers reputation. An old hand at the ice, he had been in the