In front of me, Arnhem was burning. Against a blue backcloth of sky, on a sunny spring morning, immense columns of smoke poured up from the doomed town set on wooded hills behind a river, and drifted eastward towards the German border. The centre piece was a ruined church, one side of the tower still standing, with the sky bright behind the broken windows. The sound was continuous. Our shells poured overhead into the town with the noise of thousands of tons of water roaring over a waterfall. Above them rose the high, fluttering scream of German shells about to arrive and the unearthly moaning wail of the salvoes of 150-millimeter projectiles from the German multiple-barrel mortars. A battle is read through the ears, so that although the rolling rattle of machine-gun fire sounded like two crazy xylophonists trying to outdo each other on tin trays, the slower, sweeter note of the Bren was distinct from the sharp, angry, irregular rattle of the Spandau.

A rash of dust spurts kicked up along the wall of a riverfront house, accompanied by the heavy, drilling roar of a tank machine-gun; then the Canadian Sherman lets loose with its 75-millimeter turret gun and a cloud of grey-white smoke blossomed horizontally out from the wall. A second Canadian tank crawled along the Arnhem waterfront like an enormous insect, and both tanks blasted the house, which almost disappeared in the blossoms of spurting smoke and the irregular rashes of machine-gun fire.

The bridgethe great road bridge of Arnhemdipped its shattered span into the Neder Rijn, the shorn-off girders reaching for the river like broken hands, or the hopes of its Dutch and German defenders.

The thirdand lastBattle of Arnhem was at its height.

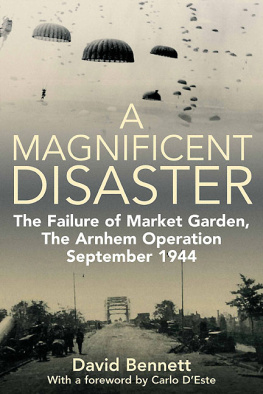

In its axis of advance it was almost an exact duplicate of the first battle, which had taken place there a month short of five years before. But because this was 1945 and not 1940, the forces engaged and the machines and weapons involved were immensely greater. And its objectives were different. They were a duplicate of the main intention behind the only Battle of Arnhem that is now rememberedthe bitter British defeat of September, 1944, which was also the last outright German victory in the West during the Second World War.

The British victory at Arnhem in 1945 was not merely the third battle for that particular town in the space of less than five years, it was also the culmination of the third great Rhine campaign of the Second World War. In these three campaigns many key pointssuch as towns, airfields, and high ground situated at and around the vital crossing placeswere assaulted twice or even three times. The soldiers who went forward to the attack or the counter-attackor who dropped from the skieswere of many nationalities: Dutch, French, Germans, British, Canadians, Americans, approximately in that order.

All three campaigns featured the use of airborne troops and two of them involved the laying of an airborne carpet along a line of bridges deep inside enemy territory, with the hope that fast-moving armoured divisions would be able to link up in time before the lightly armed paratroopers were overwhelmed. This was a genuine innovation in the history of warfare, and few of these operations went exactly according to plan. Some were chaotic failures. Yet others were brilliantly successful.

Dominating them all was the Rhine. Linking them also, although to a lesser extent, was the Ruhr.

The commercial importance of a river lies not so much in its width as in its depth; and in the regularity of the water supply, which ensures adequate depth. The Rhine is unusual in that the primary fluctuations in its supply are governed by the Alpine icecap and the Atlantic rains, and only to a limited extent by the spring thaw. In Switzerland it is an Alpine torrent with a summer flow ten times as great as that in winter. On the plains between the Vosges and the Black Forest, the Rhine is up to two miles wide in summer but a meandering pattern of half-dry channels and banks in winter.

Here in 1940 the concrete fortifications of the Maginot and Siegfried lines faced each other directly across the river and, partially dismantled, still do. This is the disputed land of Alsace-Lorraine, part-German, part-French, with its capital at Strasbourg, where the Rhine as a commercially important navigable river really begins. This plain is a result of a lowering of the earths surface by earthquake movements long ago. Because the river is easy to cross, Strasbourg has seen many invaders.

Beyond Strasbourg, the Rhine becomes more stable with the entry of major rivers that fluctuate also, but in different and therefore complementary patterns. Both the Neckar, flowing into the Rhine near Heidelberg, and the Main, which joins the main stream by way of Frankfurt and Mainz, are high in winterwhen the Rhine is low; and low in summerwhen the Rhine is high. There are still seasonal variations, but these range now from only 28,000 cubic feet of water a second in November to 70,000 cubic feet in July.

At this point also the character of the countryside changes completely, both geologically and historically. Historically, the atmosphere until now has been that of a settled Roman civilisation, as the main riverside towns testifySpeyer (AugustaNemetum), Worms (Borbetomagus), Mainz (Mogontiacum).

But when the river enters what geologists call the Rhine gorge and the tourist agencies advertise as the Romantic Rhine, the dominating atmosphere is German and mediaeval ; and the scenery is unbelievable. Here the river has cut its way through the rock of the Rhenish uplands, so that for mile after mile great cliffs and hills rise on either side and on almost every one is perched the ruin of a mediaeval castle. To see any part of the Rhine between Bingen and Bonn, especially at sunset, is to feel oneself incorporated involuntarily in a fairy tale, and it is easy to understand why most of the Rhine legends are centred on this spectacular gorge.

The best-known legend concerns the Lorelei rock, which rises almost vertically 430 feet above the river, which at that point is 76 feet deep but a mere 650 feet wide. The restriction of so much water, the rocky and irregular channel, and the fast currents and eddies so caused would indeed make it dangerous for any boatman to take his eyes off the navigation to gaze even for a moment at any sun-bathing bikini-blonde, regardless of whether or not she had her transistor radio going.

It is true that the main towns by the river are still Roman in originKoblenz (Confluentes), Bonn (Bonna)but here the Rhine was a Roman frontier and, as the ruined castles testify, a contested land for long years after the fall of Rome. And contested even more recently, as the broken piers of Remagen bridge proclaimed when I was there last, in 1952. In 1969, that is also history, already merging into the past with the Dragon Mountain and the legend of the Nibelungs among the Seven Hills across the river. Quite forgotten, at their foot, is the meeting place of Hitler and Chamberlain during the Czech crisis of 1938.

During its passage through the gorges towards the plain, the Rhine has collected additional water supplies from four more riversthe Nahe and the Moselle from the west and the Lahn and the Sieg from the east. These rivers flow through wild and hilly country and in times of heavy rain are likely to flood, a fact to which I can testify from personal experience of living in the valley of the Sieg during the winter of 194546. I saved the units stocks of champagne from the drowned cellar only just in time.