I

The Saxon Shore

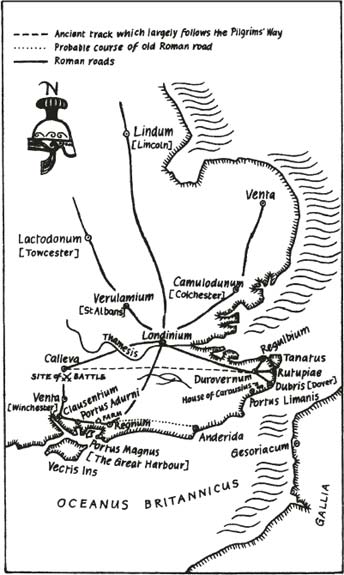

On a blustery autumn day a galley was nosing up the wide loop of a British river that widened into the harbour of Rutupiae.

The tide was low, and the mud-banks at either hand that would be covered at high tide were alive with curlew and sandpiper. And out of the waste of sandbank and sour salting, higher and nearer as the time went by, rose Rutupiae: the long, whale-backed hump of the island and the grey ramparts of the fortress, with the sheds of the dockyard massed below it.

The young man standing on the fore-deck of the galley watched the fortress drawing nearer with a sense of expectancy; his thoughts reaching alternately forward to the future that waited for him there, and back to a certain interview that he had had with Licinius, his Cohort Commander, three months ago, at the other end of the Empire. That had been the night his posting came through.

You do not know Britain, do you? Licinius had said.

JustinTiberius Lucius Justinianus, to give him his full name as it was inscribed on the record tablets of the Army Medical Corps at Romehad shaken his head, saying with the small stutter that he could never quite master, N-no, sir. My grandfather was born and bred there, but he settled in Nicaea when he left the Eagles.

And so you will be eager to see the province for yourself.

Yes, sir, onlyI scarcely expected to be sent there with the Eagles.

He could remember the scene so vividly. He could see Licinius watching him across the crocus flame of the lamp on his table, and the pattern that the wooden scroll-ends made on their shelves, and the fine-blown sand-wreaths in the corners of the mud-walled office; he could hear distant laughter in the camp, and, far away, the jackals crying; and Liciniuss dry voice:

Only you did not know we were so friendly with Britain, or rather, with the man who has made himself Emperor of Britain?

Well, sir, it does seem strange. It is only this spring that Maximian sent the Caesar C-Constantius to drive him out of his Gaulish territory.

I agree. But there are possible explanations to these postings from other parts of the Empire to the British Legions. It may be that Rome seeks, as it were, to keep open the lines of communication. It may be that she does not choose that Marcus Aurelius Carausius should have at his command Legions that are completely cut away from the rest of the Empire. That way comes a fighting force that follows none but its own leader and owns no ties whatsoever with Imperial Rome. Licinius had leaned forward and shut down the lid of the bronze ink-stand with a small deliberate click. Quite honestly, I wish your posting had been to any other province of the Empire.

Justin had stared at him in bewilderment. Why so, sir?

Because I knew your father, and therefore take a certain interest in your welfareHow much do you in fact understand about the situation in Britain? About the Emperor Carausius, who is the same thing in all that matters?

Very little, I am afraid, sir.

Well then, listen, and maybe you will understand a little more. In the first place, you can rid your mind of any idea that Carausius is framed of the same stuff as most of the six-month sword-made Emperors we have had in the years before Diocletian and Maximian split the Purple between them. He is the son of a German father and a Hibernian mother, and that is a mixture to set the sparks flying; born and bred in one of the trading-stations that the Manopeans of the German sea set up long since in Hibernia, and only came back to his fathers people when he reached manhood. He was a Scaldis river-pilot when I knew him first. Afterward he broke into the Legionsthe gods know how. He served in Gaul and Illyria, and under the Emperor Carus in the Persian War, rising all the time. He was one of Maximians right-hand men in suppressing the revolts in eastern Gaul, and made such a name for himself that Maximian, remembering his naval training, gave him command of the fleet based on Gesoriacum, and the task of clearing the Northern Seas of the Saxons swarming in them.

Licinius had broken off there, seeming lost in his own thoughts, and in a little, Justin had prompted respectfully, Was not there a t-tale that he let the Sea Wolves through on their raids and then fell on them when they were heavy with spoil on their h-homeward way?

Ayeand sent none of the spoil to Rome. It was that, I imagine, that roused Maximians ire. We shall never know the rights of that tale; but at all events Maximian ordered his execution, and Carausius got wind of it in time and made for Britain, followed by the whole Fleet. He was ever such a one as men follow gladly. By the time the official order for his execution was at Gesoriacum, Carausius had dealt with the Governor of Britain, and proclaimed himself Emperor with three British Legions and a large force from Gaul and Lower Germany to back his claim, and the sea swept by his galleys between him and the executioner. Aye, better galleys and better seamen than ever Maximian could lay his hands to. And in the end Maximian had no choice but to make peace and own him for a brother Emperor.

But we have not k-kept the peace, Justin had said bluntly after a moment.

No. And to my mind Constantiuss victories in North Gaul this spring are more shame to us than defeat could have been. No blame to the young Caesar; he is a man under authority like the rest of us, though he will sit in Maximians place one dayWell, the peace abidesafter a fashion. But it is a situation that may burst into a blaze at any hour, and if it does, the gods help anyone caught in the flames. The Commander had pushed back his chair and risen, turning to the window. And yet, in an odd way, I think I envy you, Justin.

Justin had said, You liked him, then, sir?

And he remembered now how Licinius had stood looking out into the moonlit night. Ihave never been sure, he said, but I would have followed him into the mouth of Erebos itself, and turned back to the lamp.