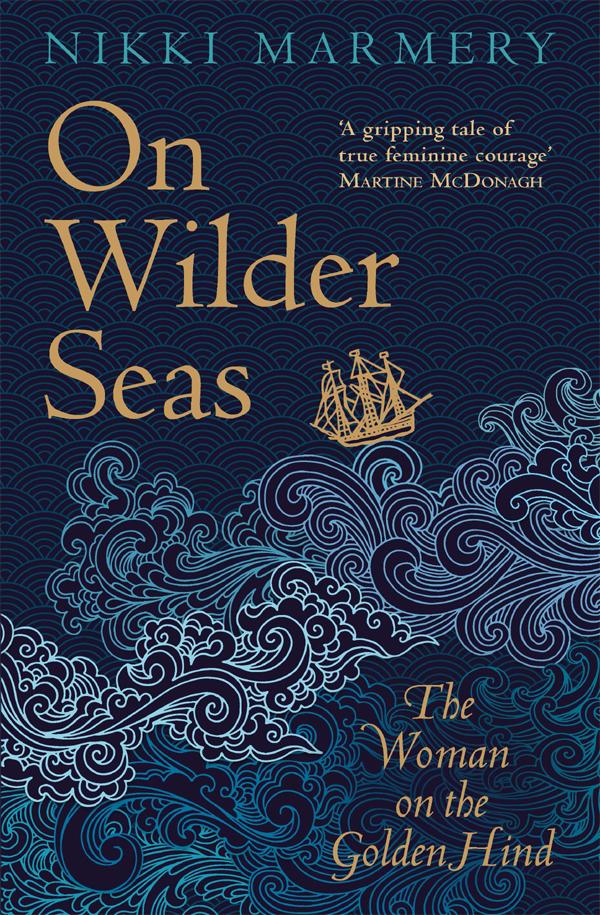

Legend Press Ltd, 51 Gower Street, London, WC1E 6HJ

Contents Nikki Marmery 2020

The right of the above author to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data available.

Print ISBN 978-1-78955-113-6

Ebook ISBN 978-1-78955-114-3

Set in Times. Printing Managed by Jellyfish Solutions Ltd

Cover design by Simon Levy | www.simonlevyassociates.co.uk

All characters, other than those clearly in the public domain, and place names, other than those well-established such as towns and cities, are fictitious and any resemblance is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who commits any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Nikki Marmery has been shortlisted for the Myriad Editions First Drafts Competition and the Historical Novel Societys New Novel Award. She previously worked as a journalist at Incisive Media.

Nikki lives in Amersham with her husband and three children.

Follow Nikki

@nikkimarmery

Book One

NOVA

HISPANIA

MARCH MAY, 1579

MARCH, 1579

ACAPULCO

1650N

1

On the day the treasures of the East are unloaded in the harbour of Acapulco, the feria begins. When the cloves, cinnamon and nutmegs, musky sandalwood and camphor oil, the silks, porcelains, ebony-wood and elephants-teeth carvings when all has been weighed, taxed and released to the merchants, the husks of the galleons inspected for contraband and sent on to the shipyard for repairs when the scurvy-sore crew are released at last to pray thanks for their lives: only then can the Fair of the Manila Galleons begin.

Now, the scorched and dusty town doubles in size. Here come the arrieros, three-legged with their staffs, leading mule-trains down the treacherous mountain path. In iron-wheeled carts come the merchants of Mxico and Jalapa, shaded under rich awnings. Soldiers to protect the cargo, and the Viceroys officials to inspect, oversee and record. On foot come the Indio hawkers and begging friars, the gamblers and the whores. By sea, the masters of the Lima ships come to fill their holds with silks to cover the calves and perfumes to scent the temples of lusty Limeos.

And here too, come I, borne here on a Lima ship, unwilling and unasked. I slip through the crowd, among these knaves and sinners, past prodding elbows and bony knees, squeezing myself wherever there is space, to bid and barter, as they do, for the cargo laid out upon tables, rugs and stalls.

Yes, I will fight for these treasures too, because only a fool sees the sun and does not ask why it is there. My grandmother was right in this as in most things. I know the sun is there to warm and delight me, as I know what can be bought here for ten pesos may be sold in the ports of Guayaquil, Paita and Lima for twenty.

If I am careful, that is. For it is not permitted. Everything I earn belongs by right to Don Francisco, since all that I am, my labour and my body, are his, may the Virgin spit on his sword and the Devil shit in his face. But if I am not discovered, it gains me some few pesos to put with the little I have in my pouch. One day it will be enough to pass to an agent to buy my freedom.

And I must be quick about it, for soon we sail. The bell of the Cacafuego rings out from the harbour. Already, her banners and pennants are raised and kicking at the wind. The red and white cross of the King of Spain flutters from the topmast. The marineros leap like monkeys about the rigging.

I run. To the back of the plaza, beyond the Hospital de Nuestra Seora de la Consolacin. I push past merchants snatching, haggling, outbidding past porters and slaves stumbling under the weight of their parcels, the painted women weaving their way, bold-eyed, through the crowd. Past the children squealing with delight at the acrobats tumbling on the wooded hill, and the Indio musicians, whose song of harps and flutes floats above it all. But the scaffold stops me. Two slaves await there today. Both men at least not children. Chained by collar and cuffs, ready for boiling fat to be poured upon their naked flesh. Runaways, then. Caught running for their freedom in the hidden places of the mountains. Their eyes are fixed there now: on the steel-grey rock rising behind the town and beyond; to the unseen narrow passes and secret valleys that would have shielded them.

I will not look. I fly. Past the torture of the slaves, to the alley where the meanest merchants linger. To the stall of the mestizo Felipe, who will keep some offcuts for me. I see him through the crowd from afar. Fuller in the belly than when I saw him last: he prospers. Bales of Chinese silks, cottons of Luzon and muslins from India overflow from three full barrel tops.

Maria! He welcomes me with outstretched arms and I fold into him. He still smells of the long voyage from Manila: the sour sweat crusted into his linen and the pitch that can never be got out of canvas.

I pull away from the stench of his armpit. What have you for me?

Nothing, moza, I thought you dead. Where were you last year?

I do not wish to think of where I was last year. I reach out to feel a beautiful silk of emerald green. God has been good to you, Felipe.

I have been good to me.

How much for a piece of this?

He snatches it away. I cannot discount that, he shakes his head. I have a family. He raises his brow and I realise I have not asked.

How is Nicols?

Well, he nods. He misses you. He looks both ways to see who is about.

Come back with the ship, he urges. Give your master the slip.

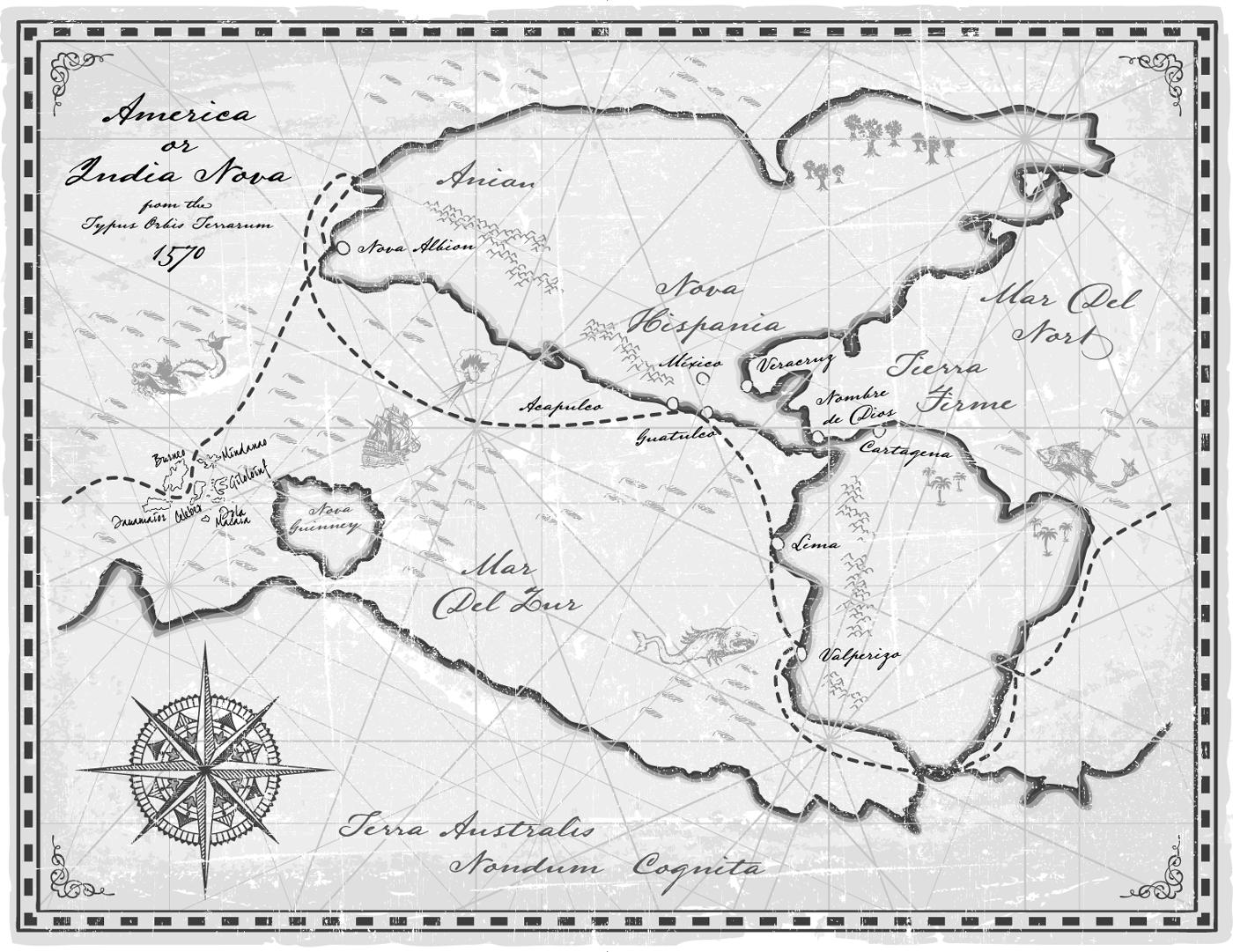

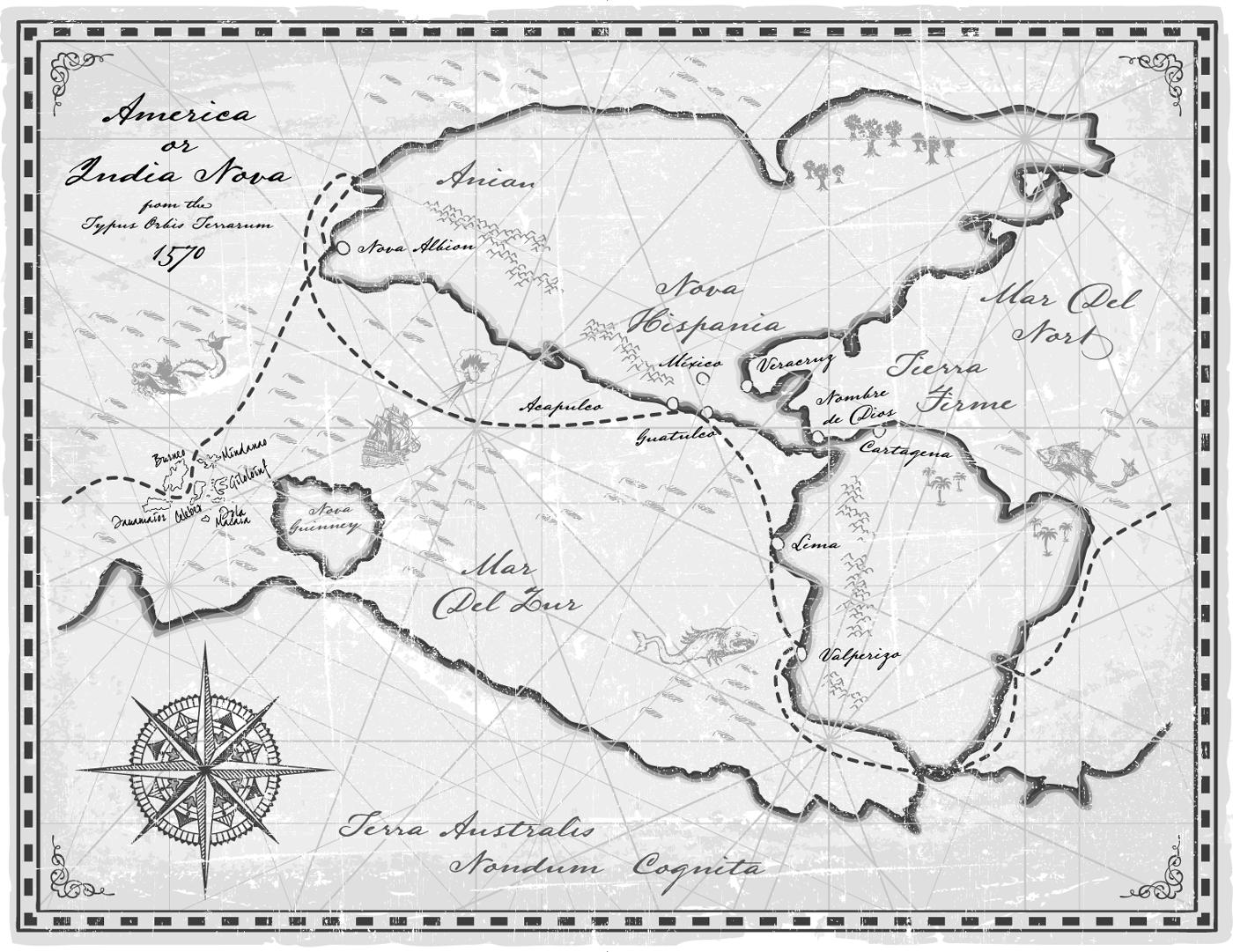

I fold my arms. Four times I have made the crossing to or from Manila and four times I made my peace to die. Twice I sailed in a fleet that lost a ship and all who were in it. Twelve weeks or more of the eternal grey sea and unblinking horizon. And what is the point? Nicols is all very well. He is a dear sweet child but he is not my own. And Manila is no different from Acapulco, or Mxico, Veracruz or Valperizo. I am a slave in every corner of this New World.

Felipe shrugs. This one I can give you for eight pesos. He offers me a bolt of black silk. A little embroidery, make a mantle of it. You can sell it in Lima for fifteen.

I scowl at him. Four.

Five, he smiles. And this for your hair. He shows me a length of calico.

I eye it greedily. My hair has been uncovered, at the mercy of every marinero who would tug and grab at it, since Gaspar the cooper pulled off my silken wrap and threw it in the sea.

I take it and gather up my salt-stiff curls into a fine double-knot at my forehead. Such relief. I fish out five coins from the pouch at my waist, poking about to check how many remain. Some forty, or thereabouts. One hundred and twenty I will need, this far from the North Ocean ports and that is if Don Francisco will take the money for my freedom, which I cannot think likely. I fold the silk and put it inside. On second thoughts, I tuck the pouch inside the waist of my skirt and arrange my camisa to hide it.