FRANS G. BENGTSSON (18941954) was born and raised in the southern Swedish province of Skne, the son of an estate manager. His early writings, including a doctoral thesis on Geoffrey Chaucer and two volumes of poetry written in what were considered antiquated verse forms, revealed a career-long interest in historical literary modes and themes. Bengtsson was a prolific translator (of Paradise Lost, The Song of Roland, and Walden), essayist (he published five collections of his writings, mostly on literary and military topics), and biographer (his two-volume biography of Charles XII won the Swedish Academys annual prize in 1938). In 1941 he published Roede Orm, sjoefarare i vaesterled (Red Orm on the Western Way), followed, in 1945, by Roede Orm, hemma i oesterled (Red Orm at Home and on the Eastern Way). The two books were published in a single volume in the United States and England in 1955 as The Long Ships. During the Second World War, Bengtsson was outspoken in his opposition to the Nazis, refusing to allow for a Norwegian translation of The Long Ships while the country was still under German occupation. He died in 1954 after a long illness.

MICHAEL MEYER (19212000) was a translator, novelist, biographer, and playwright, best known for his translations of the works of Ibsen and Strindberg. His biography of Ibsen won the Whitbread Prize for Biography in 1971.

MICHAEL CHABON is the author of ten books, including The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, The Wonder Boys, The Amazing Adventures of Cavalier and Klay, The Yiddish Policemans Union, and Manhood for Amateurs: The Pleasures and Regrets of a Husband, Father, and Son. He lives in Berkeley, California.

THE LONG SHIPS

FRANS G. BENGTSSON

Translated from the Swedish by

MICHAEL MEYER

Introduction by

MICHAEL CHABON

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

IN MY CAREER as a reader I have encountered only three people who knew The Long Ships, and all of them, like me, loved it immoderately. Four for four: from this tiny but irrefutable sample I dare to extrapolate that this novel, first published in Sweden during the Second World War, stands ready, given the chance, to bring lasting pleasure to every single human being on the face of the earth.

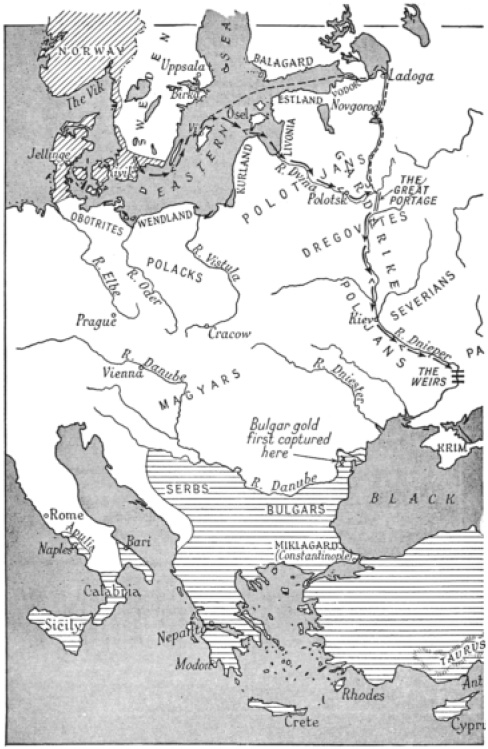

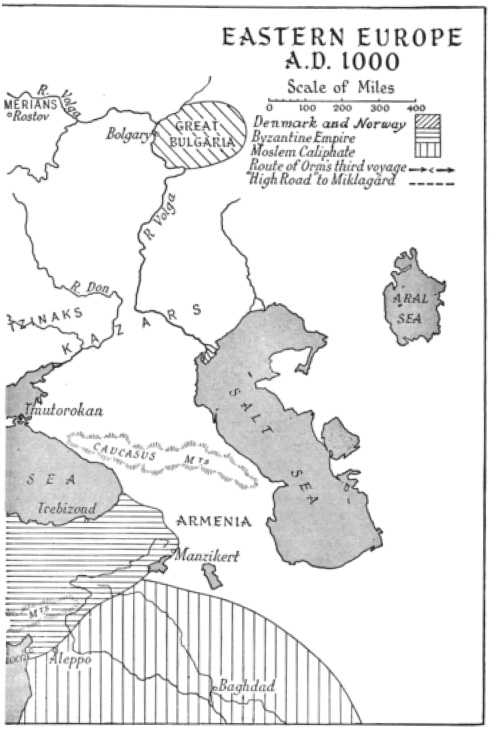

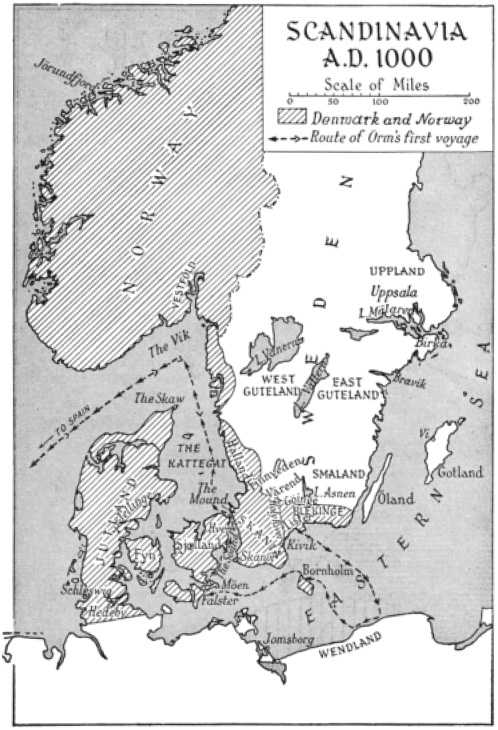

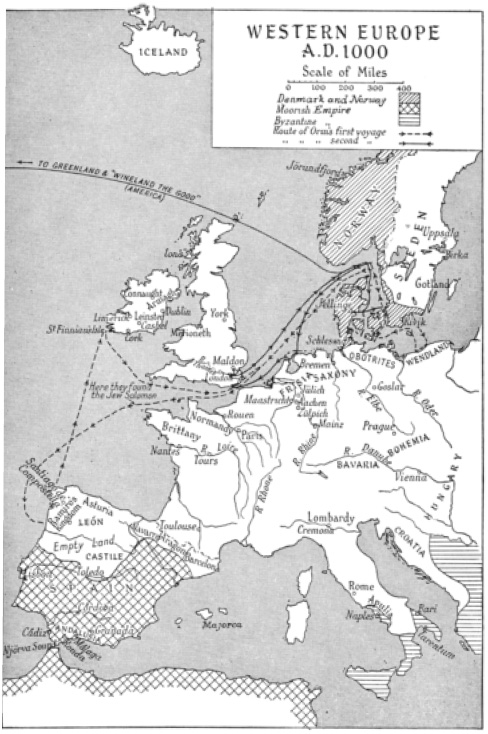

The record of a series of three imaginary but plausible voyages (inter rupted by a singularly eventful interlude of hanging around the house) undertaken by a crafty, resourceful, unsentimental, and mildly hypochondriacal Norseman named Red Orm Tosteson, The Long Ships is itself a kind of novelistic Argos aboard which, like the heroes of a great age, all the strategies deployed by European novelists over the course of the preceding century are unitedif not for the first, then perhaps for the very last time. The Dioscuri of nineteenth-century realism, factual precision and mundane detail, set sail on The Long Ships with nationalism, medievalism, and exoticism for shipmates, brandishing a banner of nineteenth-century romance; but among the heroic crew mustered by Frans Bengtsson in his only work of fiction is an irony as harsh and forgiving as anything in Dickens, a wit and skepticism worthy of Stendhal, an epic Tolstoyan sense of the anti-epic, and the Herculean narrative drive, mighty and nimble, of Alexandre Dumas. Like half the great European novels, The Long Ships is big, bloody, and far-ranging, concerned with war and treasure and the grand deeds of men and kings; like the other half, it is intimate and domestic, centered firmly around the seasons and pursuits of village and farm, around weddings and births, around the hearths of women who see only too keenly through the grand pretensions of men and bloody kings.

The book offers, thereforeas you might expect from a novel with the potential to please every literate human being in the entire worldsomething for everyone, and if until now The Long Ships has languished in the secondhand bins of the English-speaking world, this is certainly through no fault of its author, Frans Bengtsson, whom the reader comes to regardas we come to regard any reliable, capable, and congenial companion in the course of any great novel, adventure, or novel of adventureas a friend for life. Bengtsson re-creates the world of 1000 AD , as seen through the eyes of some of its northernmost residents, with telling detail and persuasive historiography, with a long view of human vanity, and with the unflagging verve of a born storytellerbut above all, and this is the most remarkable of the books many virtues, with an intimate detachment, a neighborly distance, a sincere irony, that feels at once ancient and postmodern. It is this astringent tone, undeceived, versed in folly, at once charitable and cruel, that is the source of the novels unique flavor, the poker-faced humor that is most beloved by those who love this book. Though at times the story, published in two parts each consisting of two parts over a span of several years, has an episodic feel, each of its individual components' narratives is well constructed of the soundest timbers of epic, folktale and ripping yarn, and as its hero grows old and sees his age passing away, that episodic quality comes to feel, in the end, not like some congeries of saga and tall tale but like the accurate representation of one long and crowded human life.

Nor can blame for the neglect of The Long Ships be laid at the feet of Bengtssons English translator, Michael Meyer, who produced a version of the original the faithfulness of which I leave for the judgment of others but whose utter deliciousness, as English, I readily proclaim. The antique chiming that stirs the air of the novels sentences (without ever overpowering or choking that air with antique dust) recalls the epics and chronicles and history our mother tongue (a history after all shared, up to a point, with the original Swedish), and the setting of parts of the action in Dark Ages Britain further strengthens the readers deceptive sense that he or she is, thanks to the translators magic and art, reading a work of English literature. Toss in the novels unceasing playfulness around the subject of Christianity and its relative virtues and shortcomings when compared to Islam and, especially, to the old religion of the northern forests (a playfulness that cannot disguise the authors profound but lightly worn concern with questions of ethics and the right use and purpose of a life), and the startling presence, in a Swedish Viking story, of a sympathetic Jewish character, and you have a work whose virtues and surprises ought long since to have given it a prominent place at least in the pantheon of the worlds adventure literature if not world literature full stop.