Chapter One

On his wildly swaying hammock in the Midshipmans quarters below deck, Thomas Manning tossed and turned. He faced a huge dilemma: would he take his regular watch in the morning at eight bells? Or would he jump ship and set off for a perilous adventure in the New World?

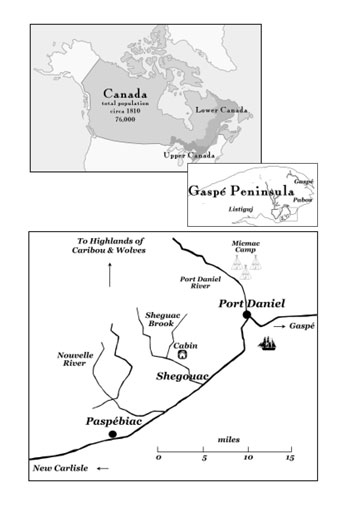

All hands on the Bellerophon, a seventy-four-gun vessel in His Majestys Navy, were exhausted from a two-day chase of a privateer up and down Chaleur Bay. They had been given leave to go to their quarters and sleep while their man owar waited out the spring storm in this sheltered bay. But Thomas could not stop fears crowding into his consciousness.

Just jump overboard and swim ashore yes, but in waters so close to freezing, the human body could not last more than a few short minutes. And if he did reach the shore, a good hundred yards away, what then? Chilled senseless, would he not make the perfect prey for wild animals that abounded hereabouts? Whatever would possess him to try?

Apart from two settlements the Bellerophon had visited, nothing covered this coastline but trees, wild animals, and Indians. Tales of terrifying tortures by savages were traded below decks in the evenings, one more horrific than another: theyd cut a mans entrails out and drape them round his neck as he hung in front of a fire, or eat his heart out in front of him as he died. No, put that right out of your mind, Thomas reprimanded himself. Arent you afraid enough?

Afraid of swimming through the spring storm that rocked and pummelled this heavy ship? Certainly. Afraid of starving to death on those snow-covered rocks? Of course. Afraid of being attacked among the barren trees by hibernating bears as starving as you are? Well, yes. And to boot, chased by the whole British Navy as a deserter? No, you must stop this, Thomas ordered, do not let yourself conjure up too much, no more thoughts of the waiting tortures. Think only of what you can achieve. Think of a farm on the cliffs, built from the very trees among which it stands. Think of a wife, broad skirt blowing in the wind, holding a child your own son. Think of trudging behind sturdy oxen, ploughing deep red furrows in rich Gasp soil. Think of the companionship of settlers, hear their pounding hammers erecting your barn, just as you would help with theirs. Think of the warmth on a frosty night by your very own fireplace, built from stones picked on these beaches, while your wife roasts one of the chickens youve raised.

But cramped in the orlop deck with its five feet of headroom, bounced in his swaying hammock with the other Midshipmen, Thomas Manning was afraid. Because he knew he was being foolish. That was the key. Foolish and inviting disaster. To take on all those bold challenges of the New World, the empty forest, the wild animals, with no experience of a pioneer life, no tools, no food, only a long-held and overpowering dream. No wonder no one else had tried to escape along this shore.

Rough as His Majestys Navy might be, hard though these disciplined quarters were, if you toed the line you were safe. Until you struck another battle. Yes, or until Wickett, the scourge of the vessel, got hold of you.

He saw his grim face again, black eyes smouldering under thick eyebrows, seeking out young Thomas, following, awaiting some slip-up. The Chief Petty Officer (nicknamed Wicked Wickett) was all the British Navy personified: a harsh discipli narian and a bold fighter. Unafraid to sentence a man for a lashing at the slightest infringement, he had proved himself so courageous in battle that Thomas at first had admired him. He had witnessed the mans consummate bravery after his left fore-arm had been blown off. Tourniqueted by the surgeon, Wickett had insisted on returning to the main deck, exhorting the sailors with a rare valour, calling out encouragement in his heavy Cornish accent. Small, dark, and swarthy as befits a true Pict from the depths of Cornwall, he represented at the same time everything that Thomas hated about the rigid structures on the ship, that same rigidity he had left behind in the Old Country. Never had he fathomed, when he joined the Navy years before, that he would be placed on a ship with such a merciless disciplinarian. He had even gone so far as to find himself slitting Wicketts throat in nightmares.

One of three who had played a practical joke on the man, Thomas would rue the day he ever joined the Navy, Wickett promised. The other two had been caught for some minor infraction, tied to the grating and lashed senseless. What Wickett threatened, he carried out. The only one left unpunished was Thomas.

But if he were to continue as a Midshipman, and if he were to evade Wicketts threats, he would be in line for the rank of Fourth Lieutenant. With that rank hed be safe from Wickett. So should he really give it all up? Throw it all away for the life of a deserter?

Why not? Thomas hated being forced to line up and watch some poor wretch flogged for a minor offence. British justice was more than he could stomach or understand. Discipline did not sit well with him, even at the Raby Castle, where his hours had been planned, jobs laid down, and all for so little reward and often few pleasures.

All this month patrolling the coast for privateers plundering merchant shipping, Thomas had waited for his chance. But a barrier of high cliffs protected the dark forbidding forests that covered the land. And there were damn few settlements along the two hundred miles of coast, certainly: one they had visited, New Carlisle, where loyal British families had fled north from the Thirteen Colonies after the Revolutionary War in 1776. But ever watchful, Wickett had made sure to cover the gun-ports with mesh, and had sent redcoated marines (the soldiers carried on every naval ship) to circle in their longboat to prevent would-be deserters escaping, even to the point of having them patrol the broad beach and muddy alleyways inland. The villagers were well aware of what would happen to anyone harbouring a deserter. So no hope there. Paspbiac, another remote settlement, was entirely French and Thomas did not speak the language; again, the marines were, as ever, watchful.