The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

For Nina, and Natty

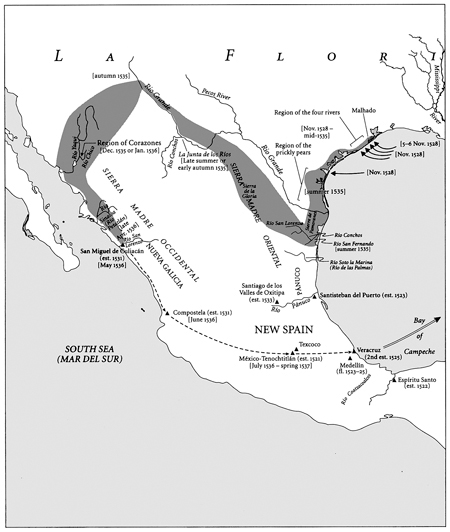

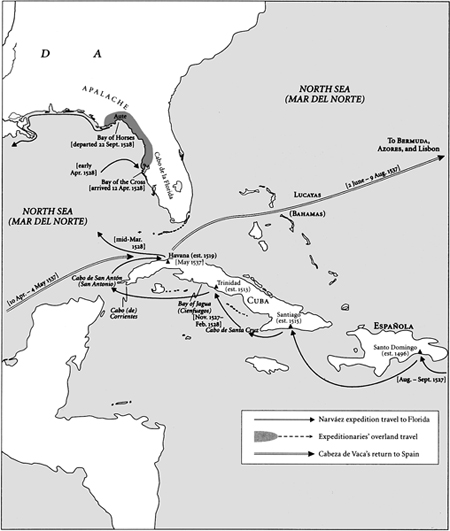

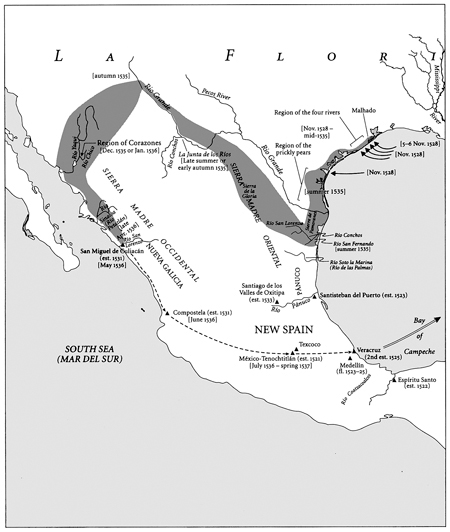

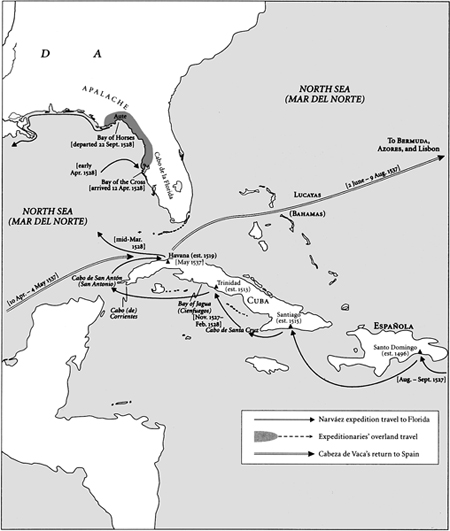

Approximate route of the Narvez survivors, 152836. (Courtesy of the University of Nebraska Press)

Introduction

On Good Friday of 1528 an army of four hundred Spaniards, Africans, and Caribbean natives landed in the vicinity of Tampa Bay, Florida, under the command of a middle-aged conquistador with a last-chance license to conquer North America. They promptly disappeared without a trace into the swamps and, except for a small contingent that remained on board the ships, were soon assumed to be dead. But then, eight years and thousands of miles later, three Spaniards and a Moroccan wandered out of what is now the United States into what was then Cortss gold-drenched Mexico.

They brought nothing back from their sojourn in the unknown north other than their story, for as one of them said later, This alone is what a man who came away naked could carry out with him. But what a tale it was. Since leaving Tampa Bay, they and their dwindling company of comrades had become killers and cannibals, torturers and torture victims, slavers and enslaved. They became faith healers, arms dealers, canoe thieves, spider eaters, and finally, when there were only the four of them left trudging across the high Texas desert, they became itinerant messiahs. They became, in other words, whatever it took to stay alive long enough to inch their way across the continent toward Mexico, the only place they were certain they would find an outpost of the Spanish Empire.

Though well known to scholars of the European invasion of the New World, Pnfilo de Narvezs expedition to Florida is surprisingly unfamiliar to most North Americans. Part of the reason, no doubt, is the relative dearth of eyewitness accounts, a not-unexpected situation given the small number of survivors and the absence of even oral traditions reflecting the Native American perspective. There are only two firsthand narratives of the mission, both flawed in their own way and both European in origin. Best known is the astonishing personal memoir of the expeditions treasurer, lvar Nez Cabeza de Vaca, whose primary goal in writing was to convince the king that he deserved to be rewarded for his sufferings and services to the crown. The other is a shorter, official report that was prepared jointly by the survivors not long after their return; unfortunately, it exists only in a paraphrased form in an early Spanish history of the Indies.

Attempting to bring some possible version of the truth into focus through these two documents alone would be like trying to discern the craters of the moon through a telescope rigged out of two lenses salvaged from two different optical devices. Its a useful and theoretically possible exercise, but often more tantalizing in the questions it opens up than authoritative about some objective reality. Fortunately, further details about the expedition can be inferred from the many other, better-documented Spanish intrusions into the region during the same period. Decisions made by Narvez can be compared and contrasted to those of his peers in similar situations, giving rise to a far more nuanced image of the commander than the traditional one of a bungling and vicious buffoon. Likewise, Cabeza de Vaca is not, in the end, quite as unerringly faithful and righteous as his own memory might suggest.

Hints about the lives and livelihoods of the various Native Americans encountered by the travelers surface in archeological reports and dissertations. Whats been learned in the last fifty years about the original inhabitants of Florida, in particular, opens the door to a more evenhanded image of the encounter between the conquistadors and the Indians. Likewise, high-tech research into the nature and volume of pre-Columbian trade within the Americas sheds new light on Cabeza de Vacas temporary career as a peddler. In Texas and Mexico, meanwhile, a century of academic debates over the probable route of the survivors has finally coalesced into something resembling consensus.

And finally, for the interested person, the saw grass shallows of the Florida Panhandle are still there to wade out into. Thunderous downpours still roll in off the baked lands outside Laredo, Texas. Some of the plants may have changed, but the Sierra Madre remain.

The end result is a mosaic of pedigreed facts that when viewed as a whole bring a plausible rendering of the story to life. Its a daunting and occasionally frustrating undertaking; in a work of nonfiction there are always some tiles missing from the mosaic. Nonetheless, the story of the Narvez expedition is well worth the effort, and not only because the ordeal of the four who survived constitutes one of the greatest survival epics of all time. Or because they were arguably the first from the Old World to cross the continent of North America. Or that their journey and their stories inspired the better-known expeditions of De Soto and Coronado that followed them.

Beyond the day-to-day drama of the journey, what the Narvez survivors saw and said they saw provides a tantalizing glimpse of native North America in the moments before the waves of disease and dislocation began to change forever the human makeup of the continent. When fleshed out with what is known from other sources, the glimpse becomes something closer to a vision, and the journeyerslost though they mostly werebecome unintentional guides to a now lost New World.

It was a world populated by neither noble savages nor bad Indians. As the survivors made their way from Florida to the Pacific, and then south, they met a dizzying array of peoples, some cruel enough to pluck mens beards out for pleasure, others kind enough to carry dying strangers to warm fires. Some were seemingly well off, dressed in fine furs and extravagant feather-work, others were desperately poor, their bellies bloated from hunger. And it wasnt just the residents of the New World that confronted the audacious newcomers; there were hurricanes and lightning, raging rivers, scorching deserts, and venomous vipers. This precontact North Americaland, water, weather, and peopleis the true protagonist of the story, against which the lives and dreams of the four hundred would-be conquerors are bent and twisted and, in all but a very few cases, extinguished.

For the expeditionaries setting out from Spain in 1527, North America began as an imagined place where they would find fabulous empires of gold: perhaps the seven lost cities supposedly settled by Portuguese bishops fleeing Muslim invaders in the early Middle Ages, or the fabled lands of the Amazon warriors, or even the fictional island of California. They would find nations of peoples waiting to be liberated from their heathen ways and ultimately thankful to be brought into the fold of civilization, even if blood had to be spilled to convince them. In the process, the adventurers believed they would become wealthy beyond anything possible if they stayed home. Coming out of a seven-hundred-year tradition of privateer warfare against the Islamic Moors in Spainthe reconquestthey saw no conflict between fighting for their ideals and their pocketbooks at the same time. They were going to North America to serve God and the king, as one of their contemporaries said, and also to get rich.