Table of Contents

PENGUIN CLASSICS CHRONICLE OF THE NARVEZ EXPEDITION

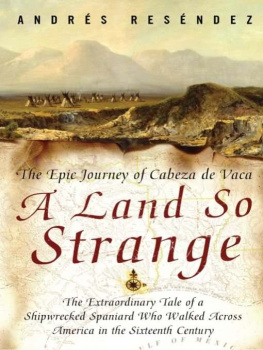

ALVAR NEZ CABEZA DE VACA was born sometime between 1488 and 1492 in the south of Spain, most likely in Jerez de la Frontera. His maternal grandfather, Pedro de Vera, was the well-known conqueror of the Canary Islands. The fourth son of a prominent family, Cabeza de Vaca served as a soldier with the forces of King Carlos V in Italy and later with the Dukes of Medina Sidonia in Spain. Cabeza de Vaca made two trips to the Indies. In 1527, he sailed with Pnfilo de Narvez through Cuba to La Florida, a disastrous expedition whose events he later transformed into the Chronicle of the Narvez Expedition, published in 1542. In 1541, he returned to the New World as the governor of the Ro de la Plata region in South America, which ended with the mutiny of several of his lieutenants and his being sent back under arrest to Spain, where he was tried for his crimes, which seem to have been little more than attempts to establish just government for both the Amerindians and the Spanish. These experiences formed the basis for his memoir Comentarios Reales (Royals Commentaries), which was published in 1555 in tandem with the second edition of the Chronicle of the Narvez Expedition, and which helped restore his reputation at court. He is believed to have died in about 1560, and was buried near his grandfather in Jerez.

ILAN STAVANS is Lewis-Sebring Professor in Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College. His books include The Hispanic Condition (1995), Art and Anger (1996), The Oxford Book of Latin American Essays (1997), The Riddle of Cantinflas (1998), Mutual Impressions (1999), and On Borrowed Words (2001). His work has been translated into six languages.

FANNY BANDELIER was a research anthropologist and teacher who specialized in the cultural history of South America and southwestern North America. She was born Fanny Ritter in 1869 in Zurich, Switzerland, and moved to Lima, Peru, in 1884. There, in 1892, she married Adolph Francis Alphonse Bandelier, an eminent researcher of the pre-Columbian and Hispanic periods of the Americas. Working together they compiled an impressive body of research findings, until his death in 1914. After his death she held various research and teaching positions, until her death in 1936. Her papers are on deposit in the Adolph Bandelier Collection of the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe.

HAROLD AUGENBRAUM is director of The Mercantile Library of New York and its Center for World Literature. Among his recent books are Growing Up Latino (1993), The Latino Reader: An American Literary Tradition from 1542 to the Present (1997), and U.S. Latino Literature: A Critical Guide for Students and Teachers (2000).

INTRODUCTION

We Americans are yet to really learn our own antecedents.... Thus far, impressd by New England writers and schoolmasters, we tacitly abandon ourselves to the notion that our United States have been fashiond from the British Islands only... which is a very great mistake.

Walt Whitman, 1883

Desnudo... In Spanish the word means naked, and its the way Alvar Nez Cabeza de Vaca likes to describe himself in his Chronicle of the Narvez Expedition. In straightforward fashion, the chronicle narrates his trekking between 1527 and 1536, from Cuba to Florida and Texas, onward to New Mexico and Arizona, and down to Mexico. I wandered through many very strange lands, lost and naked, he claims at one point, and then, at another, This is the only thing that a man who left there naked could bring back with him. This is, no doubt, a surprising, even perplexing, way to describe the state of an Iberian conquistador in his colonial quest across the American continent. Readers from the sixteenth century to the present have gotten used to adventures of courage and domination from the likes of Pizarro and Hernn Corts. Adjectives like gallant, intrepid, assertive, and outlandish easily come to mind. But not naked, which stands as an attribute of vulnerability and misfortunenot part of the mythical image of valor the machinery of the Spanish Empire spread throughout the New World from 1523 to the period of independence around 1810.

Then again, Cabeza de Vaca isnt your typical vanquisher. The self-portrait that emerges of him and his three close companions in La relacin, as the chronicle is commonly known in Spanish (the other favorite title is Naufragios) and in some English renditions as The Account, is one colored by stupefaction. A veritable descent into chaosthat is the way I prefer to see it. The Chronicle of the Narvez Expedition should be read, Im convinced, as a Dantean pilgrimage through the chambers of hell and purgatory. In modern times, this type of literature is made famous by books like Joseph Conrads Heart of Darkness, in which the European traveler finds himself, unexpectedly, at the edge of the earth, alone and lonely and unsure of his culture. It is a journey that gives room to a process of reinvention: a member of a noble lineage, Cabeza de Vaca becomes a doctor (not by accident and a hint of irony has he been called the first surgeon of Texas), a shaman, and a hero to the natives.

In his version of his adventure, Cabeza de Vaca is perhaps more honest and less falsifying than many of his contemporaries. After all, the myth of the conquistador as a mighty, larger-than-life macho has been under fire almost from the moment the Iberian army arrived on American shores. Friar Bartolom de Las Casas, the so-called defender of the Indians and the main source of dissemination of this Black Legend, accused his fellow countrymen of cruel, merciless acts of violence and sexual excess against the Indian population in the New World. He was one, although certainly the most prominent, among a handful of early witnesses and participants in the endeavor of colonization that acted as a voice of conscience. But, in truth, their reproach didnt get them too far, not far enough at least. It is no secret that the Americas, unexploredi.e., magicalas they were, were perceived in Spain and elsewhere on the Old Continent as a virginal landscape, a place for experimentation. Beyond the direct supervision of the crown Iberian testosterone went on a rampage.

To this day apologists refuse to acknowledge the destructive impulses nurtured by the conquistadors and, instead, justify the effort by any means possible. One of them is the eponymous Oxford scholar Salvador de Madariaga, author of biographies of Christopher Columbus and the nineteenth-century

libertador Simn Bolvar. In his book

The Rise of the Spanish Empire (1947), Madariaga argues:

The men who explored and conquered America did so with the scantiest material means. Their spirit did it all. Coln had set the example discovering the New World with the three caravels, the biggest of which was 140 tons. Cabeza de Vaca walked through thousands of miles of unexplored country in both the northern and the southern parts of the continent. Corts conquered Mexico with four hundred men and sixteen horses. Official help was seldom given, in fact seldom asked for, by these men who preferred to go ahead without shackles. They nearly always applied for some official sanction before starting on their expeditions of exploration and conquest, but what they sought at court was less money, weapons, ships, and horses, than the moral force to legitimate authority. No man will ever understand the Conquest who does not give its due value to this feature of it: spirited, undisciplined, anarchical, the conquerors are nevertheless obsessed by the majesty of the law and not only do they never... stand up against the king of Spain, who, distant and enigmatic, follows their fabulous adventures with an eye worried and distracted by Luther-ridden Europe, but they actually seek the sanction of the royal word for their deeds and status.