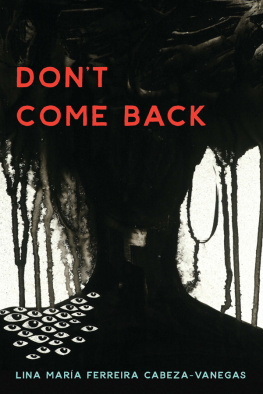

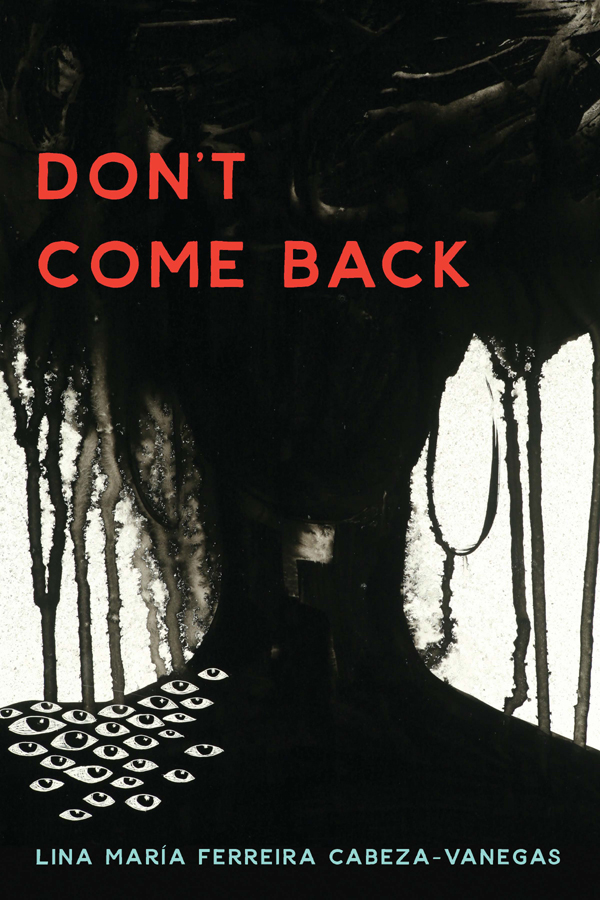

21st Century Essays

DAVID LAZAR AND PATRICK MADDEN, SERIES EDITORS

LINA MARA FERREIRA CABEZA-VANEGAS

Dont

Come

Back

Mad River Books, an imprint of

The Ohio State University Press | Columbus

Copyright 2017 by The Ohio State University.

All rights reserved.

Mad River Books, an imprint of The Ohio State University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ferreira Cabeza-Vanegas, Lina Maria, author.

Title: Dont come back / Lina Maria Ferreira Cabeza-Vanegas.

Other titles: st century essays.

Description: Columbus : Mad River Books, an imprint of The Ohio State University Press, [ 2017 ] | Series: st century essays

Identifiers: LCCN 2016039256 | ISBN 9780814253953 (cloth ; alk. paper) | ISBN 0814253954 (cloth ; alk. paper)

Classification: LCC PR 9312 ..F D 2017 | DDC /.dc

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/ 2016039256

Cover design by Nathan Putens

Text design by click! Publishing Services

Type set in Palatino and Gill Sans

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z. 1992 .

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z. 1992 .

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PARA MIS PADRES

&

FOR THE DROWNED QUEEN AT THE BOTTOM OF THE LAKE

CONTENTS

For my mother, who tried furiously to keep me from another concussion but never forbade me from climbing trees. For my father and his pathological faith in me.

For nights and nights of almost-workshops, the Canada House Collective: MHK, CC, LM, A(S)P-W, IV, KR, & AL.

For KR, who always has my back. KH, who kept me from self-indulgence. KG, for intermittently trying to poison me and keep me alive. And for KER, who told me when Id gone too far and made things too dark.

For SV, RV, and IV. For talking me down from ledges, offering me a place to stay, and countering entropy.

For BG and OG, for paying my rent, giving me a job, and helping me bury dead cats in the middle of the night.

For EM, who gave another book a home so that this one could exist.

For Dr. M, who told me to put the aphorisms back, stole me away from fiction in the first place, and pulled this book out of the abyss.

For David Lazar, who schemed with Patrick Madden on my behalf.

For the tireless and generous Mad River Books team: Tara Cyphers, Laurie Avery, Juliet Williams, and Meredith Nini.

For my kind and critical thesis committees: Aron Aji, Honor Moore, and Maureen Roberts and John DAgata, Russell Valentino, and David Hamilton.

For Graciela, Yaneth, Mara, Kelly, and all the Colombian women who tell me their stories and let me write them down.

For my grandmother, who giftwrapped hell for me, and for the colonel, who slit the heavens open with his plane.

For my aunt, who asked me to come back, and for all the gods of all the sacred lakes for giving me a country to which I could go back.

The hamsters were dead.

My sister still insists that I am to blame, and I may still wonder. Because this is certainly likely.

If you drop and throw a thing enough times, parts will eventually come loose inside it. Even if you name your hamster Little She-Rambo. Even if you slip on little bandoliers, and smear its face with mud, and drop it in a backyard-jungle obstacle course of dandelions and broken glass. Especially if you try to tie a miniature bandana around its head.

Words and reenactment are insufficient alchemy.

Tiny skulls need only tiny cracks for tiny swells and leaks to end tiny lives.

Regardless, it wasnt me. (Probably.)

More likely it was the cold slipping in from under the door with a half-rotten board nailed to it. I remember, because I was there the night my father drove in the nails.

I held my green plastic hammer as he swung his, and I kept watch for the things I thought my father meant to keep out with wooden planks and bent nails. A board over a slit between the metal door and tile floor, wood like tape over rust-covered lips. And I turned my green hammer in my hands and waitedfor the devil in the backyard, for the god of rats in the oven, for the men with rifles deep inside the mountains. For all of them to kick in the board, rip off the tape, and slip in through the crack beneath the door.

Mostly, however, rats. My father insisted, Big rats, Lina.

So, Yes, Dad, I said, rats. Except I said, Si, and I said, Si, Papi, because I was five and I didnt speak English then and words are still insufficient alchemybut here I am. Yes, Dad, ratas. And I spun my green hammer in my hands and planned on killing myself a rat. A good fat one, Una ratisima ratota.

Just for practice, just for when the others slipped in.

A brown-fur devil I saw peeking behind the tamarillo tree in the backyard one night, or the men in the news carrying AK-s, or even the soldiers they shot at who stacked bricks of cocaine in front of the screen and seemed to me, back then, to be no different one from the other. Or, rather, the three-tailed god of rats my aunt Chiqui swears she saw once in the yard, covered in purple-black feathers and yellow spikes, running on two legs and leaping into the oven as it howled.

So I imagined it. Turned my hammer in my hands and heard the coconut skull crack of many heads beneath my swing. Just like my father did when the rats squeezed under the thin slit, swinging tiny feet and shaking black fur heads until they were inside and their little claws made plick-plack noises on the tile floor. Then hed swing precisely and finally. A broomstick like a spear or a hammer like a sling. Swift and sure, down like a paperweight atop a flattened, soggy head while tails and feet twitched as if a mad wind were trying to blow the whole thing away.

So in went the nails. To keep some things in and others out. Because some are pets and some are not, its hard to tie a leash around a tamarillo tree devil and ill-advised to let the men from the mountain in and lure the rat god out.

Though, of course, they all make it inside eventually. And I carry them with me all my life.

But not yet. Right there, right then, my father had a plan.

Hammer, wood, nails.

Out rats, in hamsters.

Out the conflict, in his children.

A man crouching beside a hamster cage swinging a hammer, driving in nails and keeping out rats.

Because rats eat hamsters, too, my mother explained. They eat everything. As she scrunched up her nose as if there were whiskers under her skin trying to sprout through her pores. Disgusting. And I turned my hammer again and again, picturing rats sitting cross-legged in a circle, pulling on hamster bodies like they were trying to fold bed sheets. One on each end, tug-tug-tugging until hamsters came apart and all went down rat hatcheslegs, fur, whiskers, and bellies.

It was not the rats, however. It was the cold.

Thats what killed them. Because a wooden plank can only hold back so much.

So this is what we found on a cold Cha morning in Colombia: a stiff pair of hamsters buried in wood shavings inside a painted wire pen.

And it stopped making sense immediately. To keep them in a cage. So my older sister and I ran around the house looking for shoeboxes and old socks my father wouldnt miss. But my mother had a plan.

There is only one way to really know anything. What is inside explains what is out.

So she pulled out the hamsters and took them out to the cement bench in front of our house. Wait here, she said and disappeared into the house while I poked my dead pet with my index finger. A stiff and gummy thing beneath a cold-licked layer of fur, it was so like life and so unlike it, I poked it again. Here we are. Listo. My mother returned with an orange box cutter and a small assortment of bent metal tools. Lets see now. Vamos a ver.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z. 1992 .

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z. 1992 .