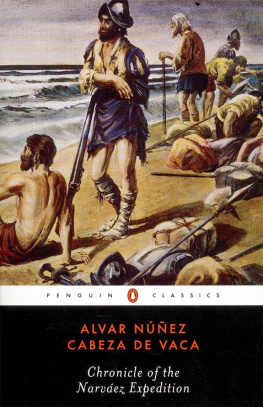

CHRONICLE OF THE NARVEZ EXPEDITION

The account Alvar Nez Cabeza de Vaca gave upon returning to Seville

COLOPHON

This treatise was printed in the magnificent, noble, and ancient city of Zamora by the honorable Agustn de Paz and Juan Picardo, partners in a printing firm and residents of the aforementioned city. The costs were underwritten by the virtuous Juan Pedro Musetti, book merchant and resident of Medina del Campo. It was completed on the sixth of October, the year of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, one thousand five hundred forty-two.

CHAPTER ONE

When the Fleet Left Spain and the Men Who Went with It

ON THE TWENTY-SEVENTH DAY of the month of June 1527, along with four other monks of the order.

We arrived at the Island of Santo Domingo, where we remained for nearly forty-five days, supplying ourselves with what was needed, horses in particular. Here more than 140 men of our army left us, wishing to remain as a result of the proposals and promises they had received from the people of the country.

Leaving there, we arrived at Santiago, a port on the island of Cuba from the aforementioned harbor of Santiago.

The governor sailed in that direction with the whole fleet, but halfway there, at a port named Cape Santa Cruz,

The following morning the weather looked ominous. It began to rain, and the sea became so rough that, although I gave permission for the men to land, when they saw the weather and that the town was a league away, in order to avoid being out in the wet and cold, many came back to the ship. At the same time, a canoe came from the town bringing a letter from a person living there, begging me to come, and saying that I would be given the supplies and whatever else might be necessary. I excused myself, saying that I could not leave the ships.

At noon the canoe came again with another letter, repeating the request, but with a great deal of insistence. They also brought a horse for me to ride. I gave the same reply as the first time, saying that I could not leave the ships. But the pilots and men begged me to leave in order to hasten the transfer of the supplies to the ships so that we would be able to sail soon from a place where they were very much afraid that the ships would be lost if they had to remain for much time. I decided to go, but before I went I left the pilots with instructions and orders that if the south wind should rise, which in those parts often causes ships to be lost, and they found themselves in great danger, they should beach the ships in order to save the men and horses. Then I left, wanting some of the men to accompany me. They refused, however, saying that it was too cold and rainy, and the town too far away. They promised to come, God willing, to hear mass on the following day, which was Sunday.

An hour after my departure, the sea became very rough and the north wind blew so fiercely that the small boats did not dare land, nor could the men beach the ships, since the wind was blowing from the shore. They spent that day and Sunday in great difficulty because of two contrary storms and considerable rain, until nightfall. Then the rain and storm increased in violence at the village as well as on the sea, and all the houses and the churches came crashing down. We had to lock arms and walk seven or eight men together to prevent the wind from carrying us off. It was no less dangerous under the trees than among the houses, since they were also being blown down and we were in danger of being killed underneath them. We wandered about all night in this storm and in danger, without finding anywhere we might feel safe for even half an hour.

In this plight we heard, all night long but especially after midnight, a great uproar, the sound of many voices, and a great noise of small bells, flutes, tambourines, and other instruments. Most of this noise lasted until morning, when the storm ended. Such a terrifying thing has never been experienced in these parts. I took depositions about it, and sent them, certified, to Your Majesty.

On Monday morning we went down to the harbor, but did not find the ships. We saw their buoys in the water, and from this knew that the ships were lost, so we followed the shore, looking for wreckage. Not finding any, we turned into the forest. Walking through it we saw, on top of the trees a quarter of a league from the water, a small boat from one of the ships, and ten leagues further, on the coast, were two men of my crew and the tops of several crates. The mens bodies were so disfigured by having been dashed against the rocks that we could not identify them. We also found a cape and a tattered quilt, but nothing else. Sixty people and twenty horses perished on the ships. Those who went on land the day we arrived, some thirty men, were all who survived from the crews of both ships.

We remained in this state for several days, in considerable need and hardship, since the food and supplies at the village had also been destroyed, as well as some cattle. The country was pitiful to see. Trees had fallen and the woods were blighted, with neither leaves nor grass.

The situation continued until the fifth day of the month of November, when the governor arrived with his four ships. They had also weathered a great storm and had escaped by moving to a safe place in time. The people on board the ships and those he found with us were so terrified by what had happened that they were afraid to set to sea again in winter and begged the governor to remain there for the season. In view of their wishes and those of the inhabitants, he decided to winter there. He put me in charge of the ships and their crews, and I was to go with them to the port of Xagua, twelve leagues away, where I remained until the twentieth day of February.

CHAPTER TWO

How the Governor Came to Xagua and Brought a Pilot with Him

AT THAT POINT the governor came with a brig he had bought at Trinidad, and with him was a pilot named Miruelo. The governor had brought the man because they said he knew the way and had been on the river of the Palms and was a very good pilot for the whole northern coast. The governor left another ship, which he had bought on the coast of Havana, so that the next day we were stranded and remained stranded for fifteen days, the keels often lying on the bottom. Then a southerly storm drove so much water onto the shoals that we were able to get off, though not without considerable danger.

After leaving there, we went to Guaniguanico, and sailed against contrary winds until we were twelve leagues off Havana. On the following day, when we attempted to enter the bay, a southerly storm drove us away, so that we crossed to the coast of Florida, reaching land on Tuesday, the twelfth day of the month of April. We sailed along the coast of Florida, and on Holy Thursday, entered the mouth of a bay on that coast, at the head of which we saw several Indian lodges and dwellings.

CHAPTER THREE

How We Arrived in Florida

ON THAT DAY THE COMPTROLLER, Alonso Enriquez, left his ship and went to an island in the bay and called to the Indians, who came over and spent a good while with him. By way of trade they gave him fish and some venison. The following day, which was Good Friday, the governor left the ship with as many men as his small boats would hold. When we arrived at the Indian huts and lodges we had seen, we found them abandoned and deserted, the people having left that night in their canoes. One of the lodges was so large it could hold more than three hundred people. The others were smaller, and we found a golden rattle among the fishnets. The next day the governor raised standards in behalf of Your Majesty and took possession of the country in Your Royal name. He showed his credentials and was acknowledged as governor according to Your Majestys commands. We likewise presented our titles to him and he complied, as was required. He then ordered the remainder of the men to disembark, along with the remaining forty-two horses, the others having perished from the great storms and the long time they had been at sea. The few that remained were so thin and weak that they would be of little use for the time being. The following day the Indians of that village arrived and, although they spoke to us, we had no interpreters and did not understand them; but they made many gestures and threats, and it seemed as if they were telling us to leave the country. With that, they left us alone, making no attempt to impede us in any way, and departed.