This edition first published in paperback in the United States in 2017 by

The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales, please contact ,

or write us at the above address.

Copyright Paul OKeeffe 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN 978-1-4683-1540-0

For Will Sulkin

M ARSHAL Grouchy would insist until the end of his life that a dispatch he received on 18 June 1815 a dispatch written at one oclock in the afternoon and which did not reach him until five had declared the battle won: en ce moment la Bataille est gagne. What Napoleons chief of staff, Marshal Soult, had in fact written was: en ce moment la Bataille est engage that the battle had begun.

A battle! the Emperor had said to his staff the evening before in a farmhouse on the road from Charleroi to Brussels. Do you know what a battle is? There are empires, kingdoms, the world or its end between a battle won and a battle lost! The same might have been said of a battle begun and a battle won. But there was little more than a transposition of characters between engage and gagne.

Misinterpretation aside, Grouchy would also insist on the physical impossibility of his complying with the order contained in an already four-hours-old dispatch: that he was not to lose an instant in manoeuvring more than 30,000 men and nearly a hundred cannon across six miles of difficult wooded country, cut by ravines,materially affected by any action Marshal Grouchy would or could have taken at five.

*

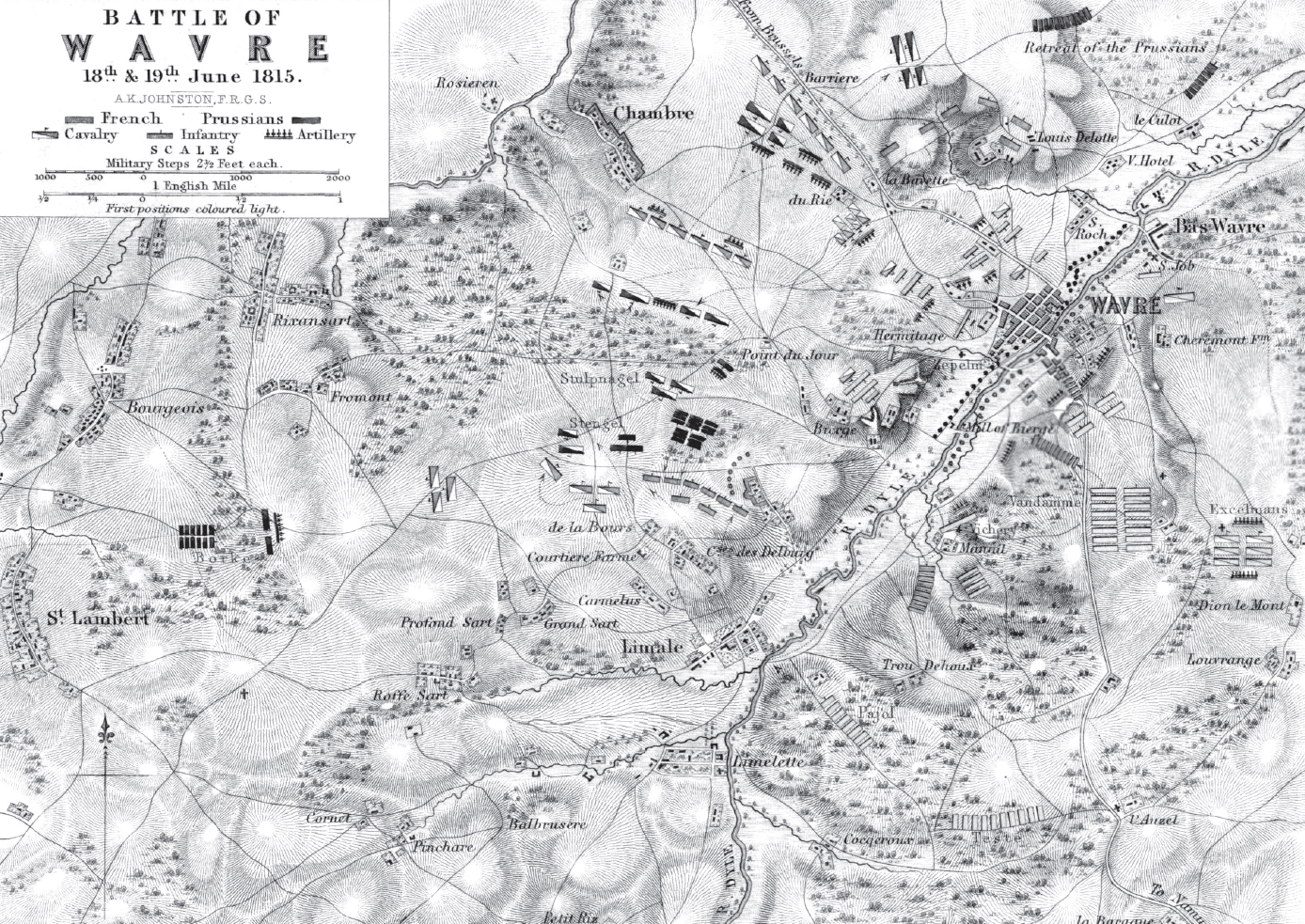

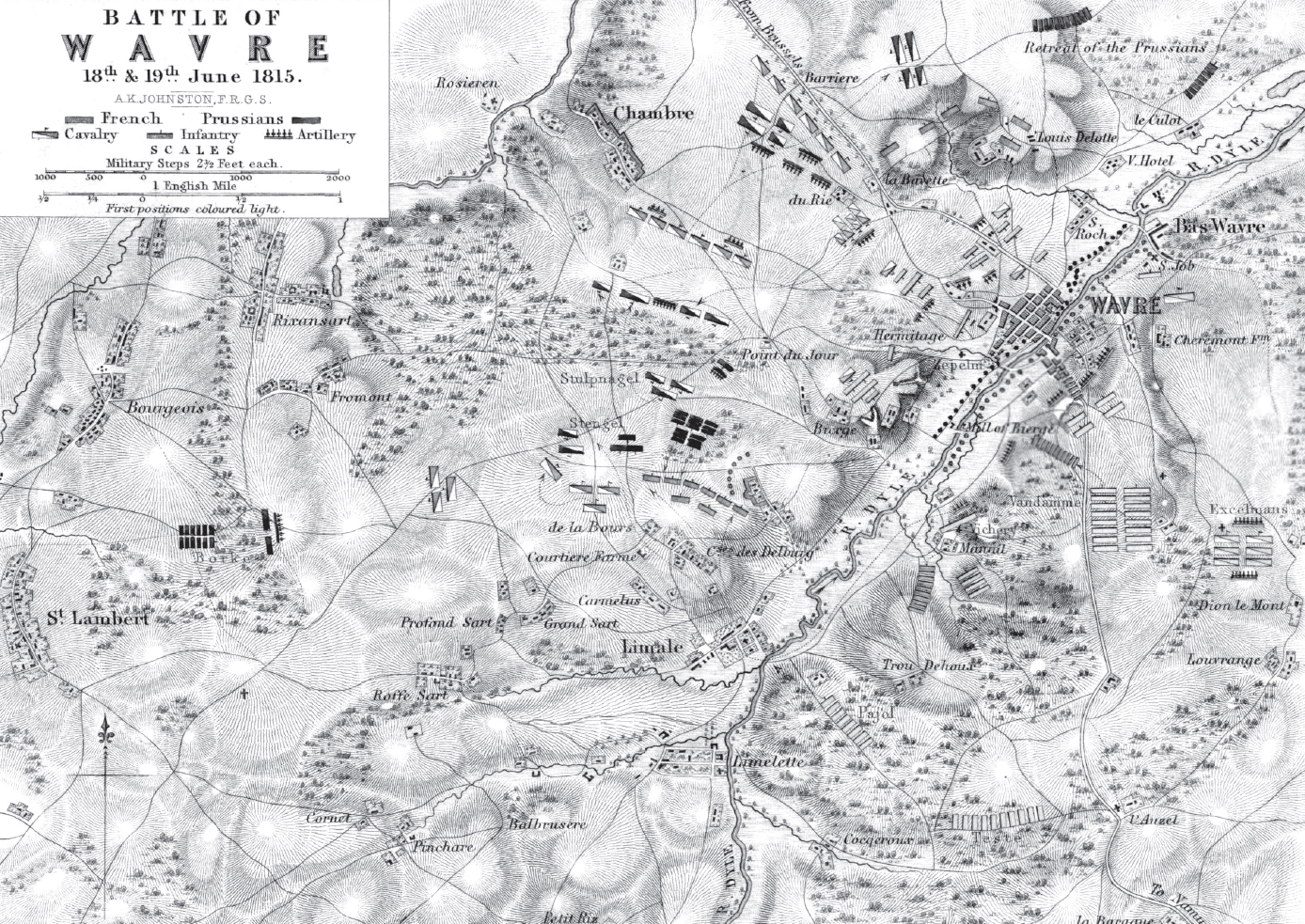

Three days earlier, Bonaparte had launched a pre-emptive campaign against the coalition of enemies massing in Belgium to threaten his restoration as Emperor of France. At dawn on 15 June, when his Arme du Nord crossed the Belgian frontier and marched towards the river Sambre, two hostile armies lay ahead. At Charleroi, and eastwards as far as Lige, were the four corps of Marshal Blchers Prussian army; north of Charleroi and to the west was the polyglot conglomeration of Britons, Brunswickers, Dutch, Hanoverians, Nassauers and Walloons constituting the I and II Corps, the Cavalry Corps and the Reserve of the Anglo-Allied army commanded by the Duke of Wellington. Napoleon had calculated that, while each of these armies could be beaten separately, their combined forces would constitute an insurmountable obstacle to his principal objective: the capture of Brussels. His strategy was to keep them apart. The road from Nivelles in the west to Namur in the east the only serviceable, cobbled route across the region, and the vital axis of communication and reinforcement linking the coalition armies was to be seized at two points. Marshal Ney, Prince de la Moscowa, commanding the French left wing of 25,000 men and forty-four guns, was ordered to capture the junction of this road with that running north from Charleroi to Brussels. The four roads radiating from the crossing gave the place its name: Les Quatre Bras. It would be defended by Wellingtons hastily mustered I Corps and Reserve. Meanwhile, the French right wing, commanded by the Emperor himself and numbering nearly 60,000 men and 216 guns, advanced on Blchers headquarters at Sombreffe, six miles from Quatre Bras along the NivellesNamur road.

By the afternoon of 16 June, battle was joined between the French and Prussians on a four-mile-wide front from Tongenelle and Sombreffe to Saint-Amand and Wagnele, with the village of Ligny at its centre, while six miles to the east, Neys forces struggled to break through Wellingtons position in front of Quatre Bras. The outcome of each battle was dependent upon that of the other. If the Emperor succeeded in disposing quickly of Blchers army, he would come to Neys assistance against Wellington and sweep in triumph to Brussels; if Ney succeeded in disposing of Wellingtons army first, he was to attack Blchers right flank and assist the Emperor in destroying the Prussian army; however, if Wellington was able to defeat Ney at Quatre Bras, he had promised to come to Blchers assistance and together they would drive the Emperor and his forces back across the Belgian border.

*

Everybody remembered the guns on 16 June. Sound travelled far in the still, hot air: a formidable spike of high pressure building to a storm.

There they go shaking their blankets again, one old soldier muttered at Enghien, just over twenty-five miles west of Quatre Bras and Ligny, as his comrades of the 52nd Light Infantry Regiment were cooking their beef ration. The sound of a distant cannonade, another veteran wrote later, is not unlike that arising from the shaking of a carpet or a blanket.

Twenty-five miles to the north, Henri de Merode, Belgian nobleman and philosopher, reading on a hilltop close to his ancestral home, Chteau dEverberg, east of Brussels, did not at first hear the gunfire, but his studies were disturbed by an unmistakable and continuous tremor underfoot. Kneeling and pressing his ear to the ground, he could clearly distinguish explosions.

They could also hear the guns of Ligny and Quatre Bras in the streets of Antwerp, fifty miles north. Magdalene for less than three months the young bride of Wellingtons acting Quartermaster General, Sir William Howe De Lancey had left Brussels eight hours before the fighting started. Antwerp was a very strongly fortified town, her husband had assured her, and likewise having the

Ten miles to the west of the fighting, somewhere between Braine-le-Comte and Nivelles, Captain Alexander Mercer was leading his troop of Royal Horse Artillery through a forest when he became sensible of a dull, sullen sound that filled the air, somewhat resembling that of a distant water-mill, or still more distant thunder. As he emerged from the trees, the sound became more distinct and, to an artillery officer especially, no longer questionable heavy firing of cannon and musketry, which could now be distinguished from each other plainly. We could also hear the musketry in volleys and independent firing. Above another forest on the horizon, volumes of grey smoke arose.

Mercers G Troop consisted of five nine-pounder guns and one heavy 5-inch howitzer, nine ammunition wagons, a mobile forge, a curricle cart, a baggage wagon and a carriage loaded with spare wheels for the guns and other vehicles. One hundred and twenty draught horses were required to pull all this equipment. Then there were horses for the officers, staff sergeants, collar makers, a farrier, a surgeon, and eight horses for each of six mounted detachments. Counting spare horses, there were 226 animals overall. Guns, wagons and horses were tended by a total personnel of 193, including three shoeing smiths, a wheeler, eighty gunners and eighty-four drivers. Perhaps at this time a troop of horse-artillery, Mercer observed, was the completest thing in the army a perfect whole.was G Troop rumbled on to join the guns at Quatre Bras.

In the borrowed Chteau Walcheuse at Laeken, three miles north of Brussels, Lady Caroline Capel, ne Paget, sister to Lord Uxbridge, commander of the Anglo-Allied cavalry, could also hear the gunfire. To an English Ear unaccustomed to such things, she wrote to her mother, the Cannonading of a Real Battle is Awful beyond description. Eight months pregnant, she had not attended Lady Richmonds ball the evening before, but her husband and two of their daughters, Georgiana and Maria Georgy and Muzzy had been there, and the juxtaposition of frivolity with a deadly artillery barrage was startling: to have ones friends walk out of ones Drawing Room into Action, which has literally been the case on this occasion, is a sensation far beyond description. At about two oclock she had first heard the distant Cannonading which approached for some time, and awful as it was every breath was hushed to listen the better [she did not] think any one of the party [at Chteau Walcheuse] felt a sensation of fear. It was Anxiety, rather, for the previous evenings dancing partners that predominated over every other feeling.