Michael Crichton

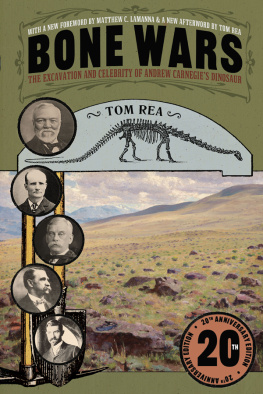

DRAGON TEETH

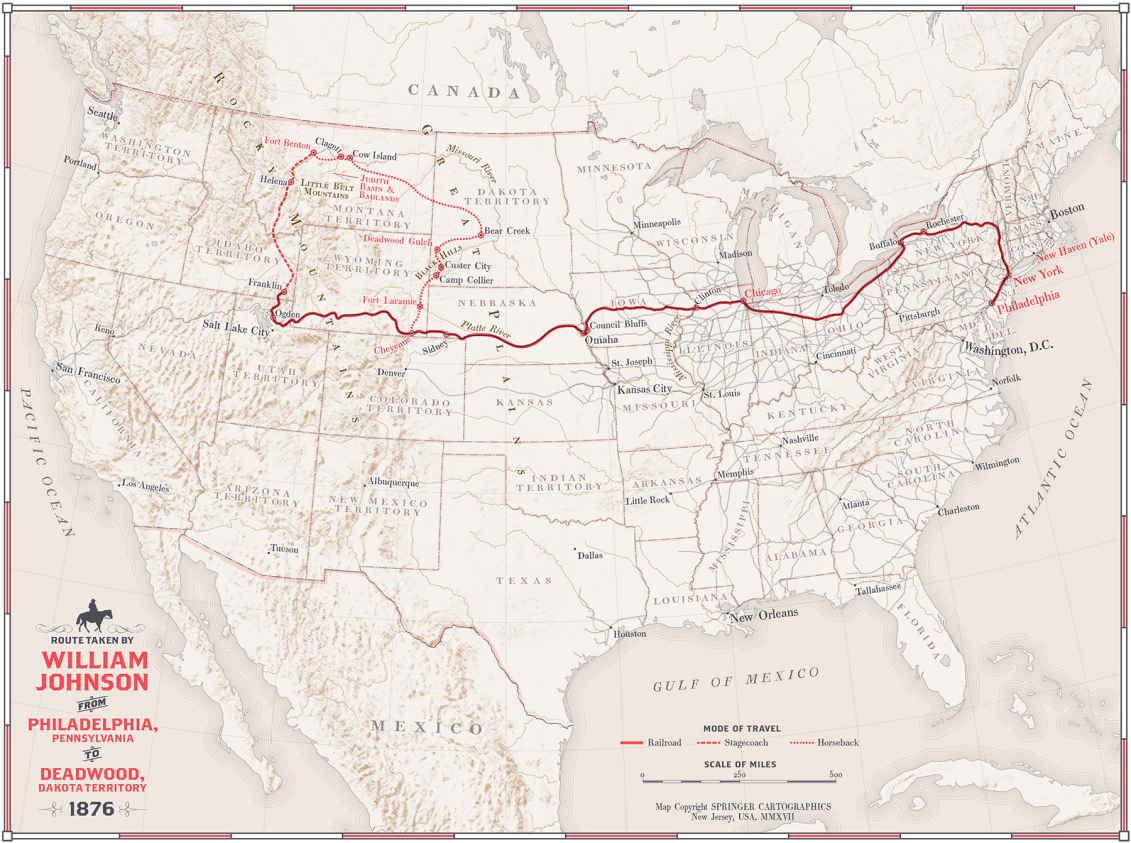

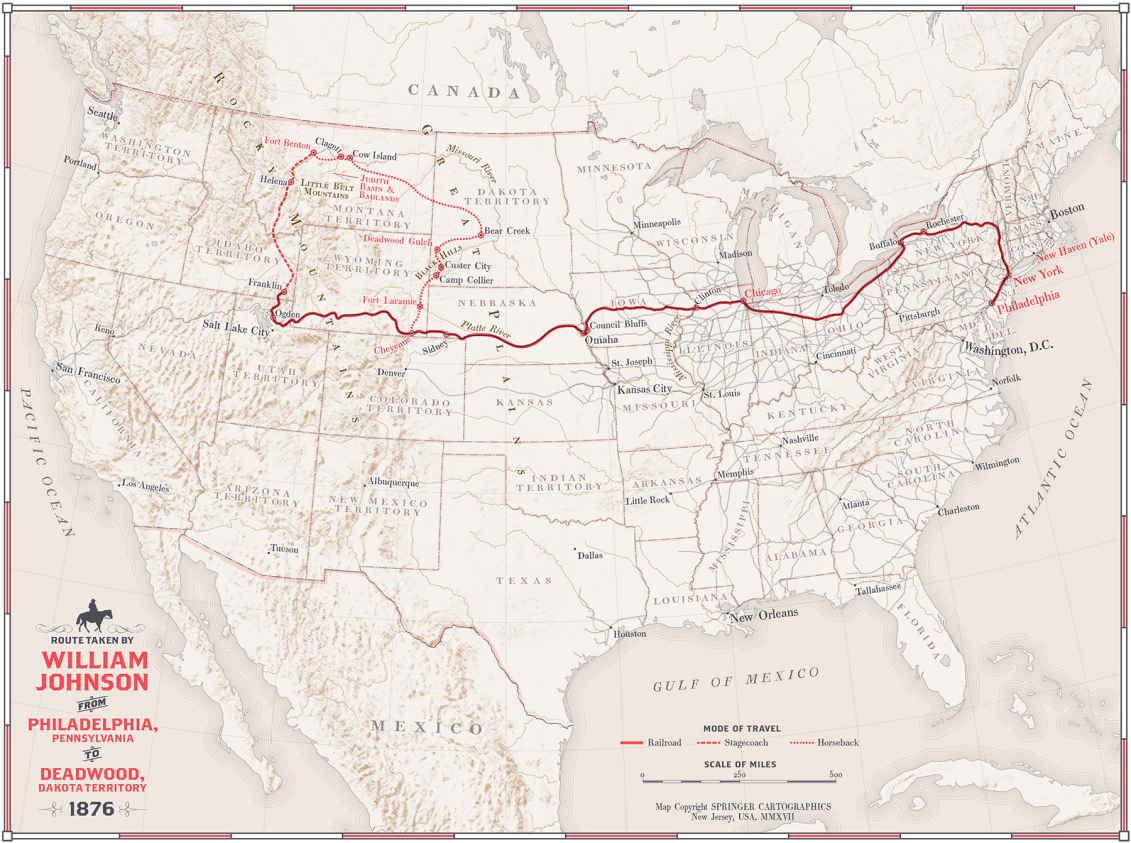

As he appears in an early photograph, William Johnson is a handsome young man with a crooked smile and a naive grin. A study in slouching indifference, he lounges against a Gothic building. He is a tall fellow, but his height appears irrelevant to his presentation of himself. The photograph is dated New Haven, 1875, and was apparently taken after he had left home to begin studies as an undergraduate at Yale College.

A later photograph, marked Cheyenne, Wyoming, 1876, shows Johnson quite differently. His mouth is framed by a full mustache; his body is harder and enlarged by use; his jaw is set; he stands confidently with shoulders squared and feet wideand ankle-deep in mud. Clearly visible is a peculiar scar on his upper lip, which in later years he claimed was the result of an Indian attack.

The following story tells what happened between the two pictures.

For the journals and notebooks of William Johnson, I am indebted to the estate of W. J. T. Johnson, and particularly to Johnsons great-niece, Emily Silliman, who permitted me to quote extensively from the unpublished material. (Much of the factual contents of Johnsons accounts found their way into print in 1890, during the fierce battles for priority between Cope and Marsh, which finally involved the U.S. government. But the text itself, or even excerpts, was never published, until now.)

Part I

The Field Trip West

Young Johnson Joins the Field Trip West

William Jason Tertullius Johnson, the elder son of Philadelphia shipbuilder Silas Johnson, entered Yale College in the fall of 1875. According to his headmaster at Exeter, Johnson was gifted, attractive, athletic and able. But the headmaster added that Johnson was headstrong, indolent and badly spoilt, with a notable indifference to any motive save his own pleasures. Unless he finds a purpose to his life, he risks unseemly decline into indolence and vice.

Those words could have served as the description of a thousand young men in late nineteenth-century America, young men with intimidating, dynamic fathers, large quantities of money, and no particular way to pass the time.

William Johnson fulfilled his headmasters prediction during his first year at Yale. He was placed on probation in November for gambling, and again in February after an incident involving heavy drinking and the smashing of a New Haven merchants window. Silas Johnson paid the bill. Despite such reckless behavior, Johnson remained courtly and even shy with women of his own age, for he had yet to have any luck with them. For their part, they found reason to seek his attention, their formal upbringings notwithstanding. In all other respects, however, he remained unrepentant. Early that spring, on a sunny afternoon, Johnson wrecked his roommates yacht, running it aground on Long Island Sound. The boat sank within minutes; Johnson was rescued by a passing trawler; asked what happened, he admitted to the incredulous fishermen that he did not know how to sail because it would be so utterly tedious to learn. And anyway, it looks simple enough. Confronted by his roommate, Johnson admitted he had not asked permission to use the yacht because it was such bother to find you.

Faced with the bill for the lost yacht, Johnsons father complained to his friends that the cost of educating a young gentleman at Yale these days is ruinously expensive. His father was the serious son of a Scottish immigrant, and took some pains to conceal the excesses of his offspring; in his letters, he repeatedly urged William to find a purpose in life. But William seemed content with his spoiled frivolity, and when he announced his intention to spend the coming summer in Europe, the prospect, said his father, fills me with direst fiscal dread.

Thus his family was surprised when William Johnson abruptly decided to go west during the summer of 1876. Johnson never publically explained why he had changed his mind. But those close to him at Yale knew the reason. He had decided to go west because of a bet.

In his own words, from the journal he scrupulously kept:

Every young man probably has an arch-rival at some point in his life, and in my first year at Yale, I had mine. Harold Hannibal Marlin was my own age, eighteen. He was handsome, athletic, well-spoken, soaking rich, and he was from New York, which he considered superior to Philadelphia in every respect. I found him insufferable. The sentiment was returned in kind.

Marlin and I competed in every arenain the classroom, on the playing-field, in the undergraduate pranks of the night. Nothing would exist but that we would compete over it. We argued incessantly, always taking the opposing view from the other.

One night at dinner he said that the future of America lay in the developing West. I said it didnt, that the future of our great nation could hardly rest on a vast desert populated by savage aboriginal tribes.

He replied I didnt know what I was talking about, because I hadnt been there. This was a sore pointMarlin had actually been to the West, at least as far as Kansas City, where his brother lived, and he never failed to express his superiority in this matter of travel.

I had never succeeded in neutralizing it.

Going west is no shakes. Any fool can go, I said.

But all fools havent goneat least you havent.

Ive never had the least desire to go, I said.

Ill tell you what I think, Hannibal Marlin replied, checking to see that the others were listening. I think youre afraid.

Thats absurd.

Oh yes. A nice trip to Europes more your way of things.

Europe? Europe is for old people and dusty scholars.

Mark my word, youll tour Europe this summer, perhaps with a parasol.

And if I do go, that doesnt mean

Ah hah! You see? Marlin turned to address the assembled table. Afraid. Afraid. He smiled in a knowing, patronizing way that made me hate him and left me no choice.

As a matter of fact, I said coolly, I am already determined on a trip in the West this summer.

That caught him by surprise; the smug smile froze on his face. Oh?

Yes, I said. I am going with Professor Marsh. He takes a group of students with him each summer. There had been an advertisement in the paper the previous week; I vaguely remembered it.

What? Fat old Marsh? The bone professor?

Thats right.

Youre going with Marsh? Accommodations for his group are Spartan, and they say he works the boys unmercifully. It doesnt seem your line of things at all. His eyes narrowed. When do you leave?

He hasnt told us the date yet.

Marlin smiled. Youve never laid eyes on Professor Marsh, and youll never go with him.

I will.

You wont.

I tell you, its already decided.

Marlin sighed in his patronizing way. I have a thousand dollars that says you will not go.

Marlin had been losing the attention of the table, but he got it back with that one. A thousand dollars was a great deal of money in 1876, even from one rich boy to another.

A thousand dollars says you wont go west with Marsh this summer, Marlin repeated.

You, sir, have made a wager, I replied. And in that moment I realized that, through no fault of my own, I would now spend the entire summer in some ghastly hot desert in the company of a known lunatic, digging up old bones.

Professor Marsh kept offices in the Peabody Museum on the Yale campus. A heavy green door with large white lettering read PROF. O. C. MARSH. VISITORS BY WRITTEN APPOINTMENT ONLY.