All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Foreword

U -48 , a Type VII B, was the most successful U-boat of the Second World War, carrying out twelve patrols and accounting for 57 vessels, including a Royal Navy sloop, with a total gross tonnage of just under 322,500. Yet her active war ended in June 1941 and thereafter she was used as a training boat. Thus her story is very much one of the early phases of the Battle of the Atlantic, with both the German and Royal Navies suffering from shortages, especially in numbers of U-boats and convoy escort vessels.

Both sides set out to observe the terms of the 1930 London Naval Treaty, which had been signed by all the naval powers, including Germany. This stressed the need for the crews of merchant vessels to have the means to reach land or another ship before their own was sunk. Admiral Karl Dnitzs U-boat skippers were initially very careful to follow this rule. As the author describes, the usual practice was to halt a vessel by firing a shot across its bows, summon the captain across and inspect his papers. If it was a neutral vessel, sailing to a neutral port, it would be sent on its way unharmed. If it had contraband goods and was bound for an enemy port the crew would be ordered to take to their boats and once this had been done their ship sunk. Because the U-boat was on the surface throughout, it was vulnerable. Yet because convoying only applied to ships able to steam at certain speeds, there many sailing alone and unescorted during the early months of the war and so the danger to the U-boat was not nearly as great as it might have been.

In spite of this, the sinking of the liner Athenia by U-30 on 3 September 1939 caused the British to believe that the Germans had embarked on unrestricted submarine warfare. Furthermore, Winston Churchill, occupying the same position of First Lord of the Admiralty as he had done in 1914, insisted on taking the war to the U-boats. One of the measures he took was to begin arming merchant vessels and once the Germans became aware of this they considered themselves entitled not to abide by the London Treaty, as they did ships sailing under escort.

Dnitz and his crews did, however, suffer other frustrations. First was the problem of having too few U-boats to make a significant impression at the outbreak of the war, and this in spite of the sinking of the aircraft carrier Courageous and the elderly battleship Royal Oak . At root lay Hitlers Plan Z expansion programme for his navy, with its emphasis on surface ships and initially not due to be completed until 1948. It meant that it was only possible to have up to some ten boats on patrol and while he did at times attempt to form wolf packs to intercept convoys, their small size meant that they could only cover a very limited part of the ocean.

The other major frustration was torpedoes, many of which malfunctioned. Franz Kurowski makes more than clear the intense frustration of the U-boat crews, not least that of U-48 . The fault lay firmly with the Torpedo Research Institute and the Torpedo Inspectorate, which consistently ignored the fact that there was a problem. Matters reached a head during the Norwegian campaign, when few torpedoes worked and a significant number of British warships lived to fight another day as a result. Only after this was urgent action taken and torpedo reliability improved.

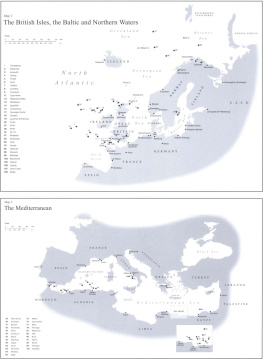

The fall of France in June 1940 and the subsequent deployment of U-boats to the French Alantic ports marked the beginning of what the U-boat crews called the First Happy Time. By drastically cutting the time needed to deploy from port to operational areas more U-boats could remain on station and wolf packs now really began to come into their own. This is graphically illustrated by the major successes against Convoys SC7 and HX79 in autumn 1940, in which U-48 played a major part. Indeed, Allied shipping losses for September and October rose to over 400,000 tons per month.

By the early summer of 1941 the U-boat fortunes were on the wane. Increasing numbers of escorts, more maritime patrol aircraft, better anti-submarine detection equipment and improved escort tactics all helped to swing the pendulum the other way. An indication of this came on 25 March, when Doenitzs HQ war diary noted that five U-boats with veteran crews were no longer answering radio messages; they had all been sunk. Perhaps it was symbolic that U-48 s last patrol would involve supporting the wounded Bismarck as she attempted to seek haven at Brest. She never made it and the U-boats in the area were then involved in looking for survivors of her crew. Then, U-48 moved towards the Azores, as part of Dnitzs tactic of turning his attention to the West African coast, where convoys were less well guarded.

Not mentioned in the book is the effect of Ultra on the Battle of the Atlantic. True, this was very limited during the period at U-48 was operational, but the seizure of Enigma rotors from the trawler Krebs in February 1941 and the capture of a complete Enigma machine from U-110 in May meant that the Submarine Tracking Room in the Admiralty began to have a much clearer idea of the German tactics. This enabled some convoys to be rerouted so as to avoid wolf packs.

There would be a Second Happy Time, when the U-boats were able to wreak havoc off the US Eastern Seaboard during the six months after the United States entered the war. Another grim time for the Allies occurred during the first months of 1943, largely because the Germans had installed an extra rotor in the Enigmas use by the U-boats. The decisive time came after the Allies finally managed to close the Black Gap, that area of the North Atlantic which was devoid of air cover. T hereafter the Battle of the Atlantic swung increasingly in their favour, although the U-boats would continue to operate right up until the bitter end.

As for the story of U-48 , it illustrates all too clearly that war boils down in the end to the performance of human beings operating under enormous stress. This U-boat was blessed with three highly professional skippers and an exceedingly well trained crew. Thus, it was able to rise to every challenge, not least because of the entire confidence felt by the crew in their captain.

Charles Messenger

CHAPTER 1

The German U-Boat Arm: Development and Command

W hen the representatives of the German Reich and Great Britain signed the Anglo-German Naval Treaty on 18 June 1935, they agreed that Germany would limit her fleet of naval vessels to 35 per cent of British numbers except in submarines, where the limit would be 45 per cent. The treaty even went so far as to allow the U-boat fleet to equal the British in numbers if approved following bilateral discussions.