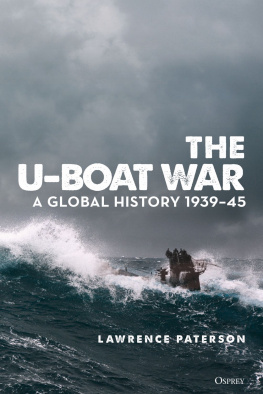

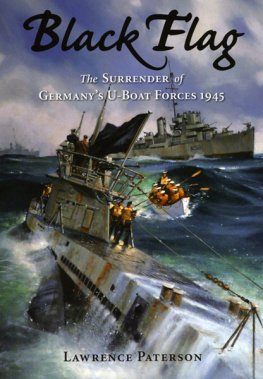

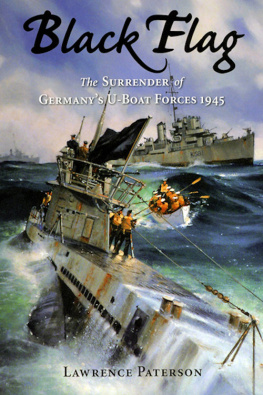

Copyright Lawrence Paterson 2009

First published in Great Britain in 2009 by

Seaforth Publishing,

Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street,

Barnsley S70 2AS

www.seaforthpublishing.com

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 84832 037 6

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 78346 913 0

PRC ISBN: 978 1 78346 680 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any

means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and

retrieval system, without prior permission in writing of both the copyright owner and the above publisher.

The right of Lawrence Paterson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted

by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Typeset and designed by MATS Typesetters, Leigh-on-Sea, Essex

Manufactured in the United States of America by The Maple-Vail Manufacturing Group, York, PA.

Contents

Foreword

In May 1945 Nazi Germany surrendered to the Allied nations with whom it had waged war over the previous six years. During the course of this great conflict the lands conquered by the Third Reich stretched from the sands of North Africa to the frozen steppes of Russia, with the greater part of mainland Europe and Scandinavia falling under occupation. However, the high tide of German empire-building broke in 1942 and nearly three years of retreat followed. Germany had neither the men or resources required to maintain what it had taken in the face of the enormous reserves accumulated by the Allies, notably the United States and Soviet Union.

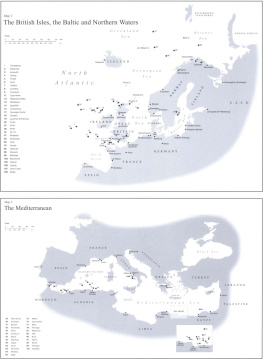

At sea, the Kriegsmarine had waged war in four oceans and five seas, this onslaught spearheaded by Grossadmiral Karl Dnitzs U-boat service. However, as on land, it was a battle of attrition that he could not win. Bested by Allied numbers, tenacity and technology, the German U-boat services chance at victory ended in May 1943 and they, too, fought a defensive battle for the remainder of the war. Despite this fact, the boats which were largely becoming obsolete by the end of 1944 continued to sail and attack wherever they could. Brief successes against an all-powerful enemy, whether localised success in small group offensives, or single kills made in lone-wolf patrols, were achieved right up to the final days of combat, whereupon the U-boats were ordered to cease fire and face the certainty of a humiliating surrender.

On land, the dispirited remnants of military formations, savaged in combat, were herded into confinement by the victorious armies. However, as well as the task of disarming thousands upon thousands of soldiers, there also existed large enclaves of Kriegsmarine personnel which still stretched from France to Norway in ports and bases from which the U-boats had operated. These men remained fully armed and almost unbroken in battle as Allied forces arrived to disarm them. In France, several of the harbour towns that had hosted the U-boat flotillas had been successfully defended against Allied siege troops, and were forced to surrender only because of the ending of the war. The complicated task of taking Germanys U-boat men into captivity often fell to small units of Allied troops, vastly outnumbered by crowds of unbowed German troops, many of them youngsters unwilling to consider their nation vanquished.

Coupled with the men ashore were those U-boats which still operated on a war footing around the United Kingdom, off the coasts of the United States, and as far away as Malaya. These had to be located before being shepherded into harbours where their surrender could be effected. For many Allied naval and air force personnel it was their first glimpse of the dreaded U-boat menace, and both sides were forced to exercise considerable restraint to avoid compromising the terms of Germanys surrender.

After this surrender, Dnitzs men were incarcerated with varying degrees of severity. Several were brutally interrogated by American intelligence officers in attempts to discover what potential weapons had been developed in conjunction with the Japanese, with whom the Allied powers were still at war. Elsewhere, German submariners found themselves held in prisoner-of-war camps that stretched from Canada and the United States to Britain. Many would not see their homeland until years after the end of the war. In the Far East, their erstwhile allies, the Japanese, incarcerated many U-boat men until Japans eventual surrender some months later. The surrendered German forces were witness to much of the agony of Japans troops and civilians in the dying months of the war which saw frequent bombing.

Meanwhile, Germanys underwater weaponry was eagerly seized and examined by the victors, particularly the Type XXI and XXIII electro-boats and Walters hydrogen peroxide propulsion units installed aboard a handful of experimental boats. Interest was so high that even the American President Harry Truman boarded the Type XXI U-boat that had been commanded by the Ace Erich Topp; this resulted in an almost comical episode as the boat submerged and suffered a brief power failure, at which point the Secret Service men surrounded their Commander-in-Chief, amidst fears of a coup dtat aboard the dreaded German U-boat.

Eventually, the majority of Dnitzs surrendered U-boat fleet was to be disposed of by the Allies in various ways, some providing targets for a certain limited amount of firing practice by Allied aircraft and naval vessels, whilst others represented a small measure of symbolism about Allied triumph over the much-feared U-boat threat.

Germanys submariners were much maligned in Allied propaganda, this image of savage cunning being reinforced by their seeming unwillingness to refrain from offensive action right up to, and regretfully beyond, their orders to cease fire being transmitted from Germany. Allied reasoning that only the hardcore Nazi element would continue to fight such a clearly lost war was nave and incorrect. This assumption was mostly made by people who were not only unaware of the grim realities accepted by most U-boat men about their slim chances of survival, but who had also forgotten that a similar kind of dogged determination had led to Britain remaining steadfast when faced with disaster in 1940, Soviet forces counter-attacking in the winter of 1941 even after being roundly beaten by the Wehrmacht, and American troops summoning the strength and determination to hold their position at Bastogne in the face of overwhelming German assault. Such courage in the face of almost certain annihilation did not require the political motivation often ascribed to Nazi forces, or indeed to the Soviet troops who suffered the most within the ranks of the Allies.

In May 1945 the task of disarming and accepting the surrender of the U-boats fell primarily to the invading Allies from the West. Those that were taken by the Soviets were largely swallowed up into the unforgiving Gulags and the quest for secrets that would become hidden behind the rapidly-descending Iron Curtain. This is the story of the surrender of Dnitzs Grey Wolves at sea, in trenches on the French Atlantic coast, and in the battered cities of northern Germany.

Acknowledgements

There are always many people involved in the writing of a book such as this. I would like to begin by thanking Aki, Megz and James of the Paterson clan (British Section), Nami, Ernie (American Section), Audrey Mumbles Paterson and Don Mr Mumbles, and Ray and Philly Paterson of the New Zealand branch. Plus, special mention to Julia Hargreaves who has been a constant source of encouragement throughout this and other books.

Special thanks for help and inspiration go to a long list of people, particularly Jak Mallmann-Showell; Mike, Sheila, Mitch and Claire French; Cozy Powell (RIP); Dave Andrews; Cath Friend; Tina Hawkins; Paul The Rg Rogne; Blaze Bayley Cooke; Dave Leonardo Bermudez; Jeremy Walsh; Nicolas Petit Porc Bermudez.

Next page