FAMILY HISTORY FROM PEN & SWORD

Birth, Marriage and Death Records

David Annal and Audrey Collins

Tracing Your Channel Islands Ancestors

Marie-Louise Backhurst

Tracing Your Yorkshire Ancestors

Rachel Bellerby

Tracing Your Royal Marine Ancestors

Richard Brooks and Matthew Little

Tracing Your Pauper Ancestors

Robert Burlison

Tracing Your Huguenot Ancestors

Kathy Chater

Tracing Your Labour Movement Ancestors

Mark Crail

Tracing Your Army Ancestors

Simon Fowler

A Guide to Military History on the Internet

Simon Fowler

Tracing Your Northern Ancestors

Keith Gregson

Your Irish Ancestors

Ian Maxwell

Tracing Your Scottish Ancestors

Ian Maxwell

Tracing Your London Ancestors

Jonathan Oates

Tracing Your Tank Ancestors

Janice Tait and David Fletcher

Tracing Your Air Force Ancestors

Phil Tomaselli

Tracing Your Secret Service Ancestors

Phil Tomaselli

Tracing Your Criminal Ancestors

Stephen Wade

Tracing Your Police Ancestors

Stephen Wade

Tracing Your Jewish Ancestors

Rosemary Wenzerul

Fishing and Fishermen

Martin Wilcox

Tracing Your Canal Ancestors

Sue Wilkes

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by

P E N & S W O R D F A M I L Y H I S T O R Y

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Imperial War Museums 2012

PRINT ISBN 978 1 84884 501 5

PDF ISBN: 9781783376568

EPUB ISBN: 9781783376582

PRC ISBN: 9781783376575

The right of Imperial War Museums to be identified as the Author of this Work

has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by

any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher

in writing.

Typeset in Palatino and Optima by

Phoenix Typesetting, Auldgirth, Dumfriesshire

Printed and bound in England by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of

Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime,

Pen & Sword Military, Pen & Sword Discovery, Wharncliffe Local History,

Wharncliffe True Crime, Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen &

Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Remember When,

Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

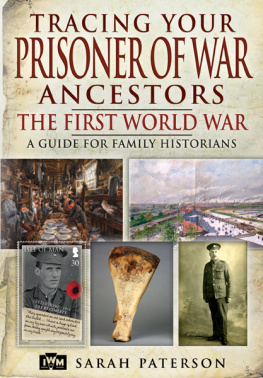

Cover illustrations, clockwise from top left: Waiting for Dinner in the Huts by

George Kenner ( Kenner Bedford/photo: IWM, ART 17089), Panoramic View of

Ruhleben Prison Camp by Nico Jungman ( IWM, ART 522), Private Charles

Kirby ( the author), Ruhleben ox bone ( IWM, EPH 3802), Isle of Man stamp

featuring Second Lieutenant R F Corlett ( Isle of Man Post Office)

DEDICATION

In memory of my father, Eifion Wyn Roberts, 19372010

CONTENTS

Appendix 1 Quick Guide to Key Resources for Tracing Prisoners of War and Civilian Internees in the First World War

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

F ounded in 1917, Imperial War Museums (IWM) has always helped people to discover the wartime or military experiences of family members. For nearly a quarter of a century I have been at the core of the team active in this type of work, and the demand continues to grow. Some aspects of this military genealogy are more difficult and complex than others, and the prisoner of war (POW) experience in the First World War is one of these. There has been a long-felt need for a guide to assist people researching this subject: many records simply have not survived, and it is not as well documented as captivity in the Second World War. I know from experience the type of questions that are frequently asked, and also where people are likely to get stuck. In this book I have concentrated on areas where information is sparse, rather than on other subjects such as escapes, which are well covered in records and literature (but directions to these are given for furthering this research). The book is aimed at those who know little about the subject, but the lists of camps and other information contained in these pages should appeal to anyone interested in POWs and internees in the First World War.

This book deals mainly with the experiences of British POWs and internees held by the Germans and Turks during the First World War. It also covers prisoners and internees held in the United Kingdom. The Quick Guide to Key Resources in provides an instant overview of where records are to be found, with the different chapters going into more detail about what the records contain, and providing useful context through case studies.

Personal experiences assume an enormous importance in the absence of other records, and IWM is a vast repository of these. Most of the case studies in this book are drawn from IWM Collections, and there is a wealth of material available to those who are able to visit the museums research facilities in London. Increasing amounts of material can also be found on the website www.iwm.org.uk and readers are welcome to make enquiries by post, telephone or email.

Many of my colleagues at IWM have been immensely helpful in the writing of this book, and it has resulted in several animated discussions about different aspects of First World War captivity. I am also very grateful for assistance from other experts in this field outside IWM, and to the archives and libraries where I have conducted research. A great pleasure resulting from this has been the contact with the families of the men whose papers and stories are held at IWM, and their permission to include these. Needless to say, any mistakes contained here are mine alone.

Here, the term prisoner of war is taken to mean members of the armed forces captured and imprisoned by an enemy power during conflict, while the term civilian internee is taken to mean a civilian who has been imprisoned by an enemy power. During this period these terms were often used interchangeably, which can sometimes cause confusion. Very few women were interned in the First World War and here all POWs and internees are referred to as men.

The POW experience is almost one of the hidden histories of the First World War. Statistically speaking, few men of the fighting forces were taken captive fewer than 3 per cent of British service personnel serving on the Western Front (the theatre of war with the largest number of British POWs). For most, it would have been a completely alien situation; servicemen may have thought about being killed or wounded on active service, but being captured was probably not a possibility they even considered. There was no training or advice about what to do in the event of being taken prisoner by the enemy (this was one of the lessons learned for the Second World War). This also applied to civilians interned in enemy countries. Approximately 192,000 British and Commonwealth servicemen became POWs. Over 16,000 did not return, and those that did were often reluctant to talk. Their experiences, usually painful, were frequently beyond the comprehension of family or friends, and their own desire to forge a new life or to retreat into the comfort of a former routine has meant that surprisingly little is known about an aspect of the war that had a profound effect on those unfortunate few.

The public perception of the POW experience relates almost exclusively to what happened in the Second World War. Film and television representations such as

Next page