IT IS MIDNIGHT IN CHICAGOS Grant Park on November 4, 2008. Barack Obama has just been elected the first black president of the United States of America by a formidable majority. He stands on a platform in the cold night air and tells one hundred thousand cheering supporters: Its been a long time coming, but tonight, because of what we did on this day, in this election, at this defining moment, change has come to America.

Some in the crowd, or watching at home, recognize the line as a paraphrase of words written by the soul singer Sam Cooke almost exactly forty-five years ago: Its been a long, a long time coming / But I know a change gonna come. At this historic moment, one of the greatest orators of the day has borrowed the most memorable line of his acceptance speech from an old protest song.

Obama is, in a sense, the first protest song president. He grew up on the politicized soul of Stevie Wonder and used Curtis Mayfields civil rights anthem Move on Up at his election rallies. During the campaign, a list of his ten favorite songs printed in Blender magazine included Whats Going On by Marvin Gaye, Gimme Shelter by the Rolling Stones, Think by Aretha Franklin, and Will. I. Ams Yes We Can, which was written around a recording of his own speech, thus making him the lyricist of his own protest song. At his inauguration concert, veteran protest singer Pete Seeger joined Bruce Springsteen to sing Woody Guthries This Land Is Your Land Stevie Wonder performed Higher Ground and Bettye LaVette and Jon Bon Jovi sang, inevitably, Cookes A Change Is Gonna Come.

Yet even as the music of the past spoke powerfully to the current moment, a giant question mark continued to hang over the future of the form. During the previous decade, newspaper articles had appeared with clockwork regularity asking where all the protest songs had gone; I wrote a couple myself. There were plenty of reasons to be fearful, angry, and occasionally hopeful during those years, but songwriters seemed, for the most part, unable to translate any of them into compelling art. One purpose of this book is to explain why that might be.

The phrase protest song is problematic. Many artists have seen it as a box in which they might find themselves trapped. Joan Baez, who sang for civil rights and against the war in Vietnam, once said, I hate protest songs, but some songs do make themselves clear. Barry McGuire, who sang the genre-defining 1965 hit Eve of Destruction, protested, Its not exactly a protest song. Its merely a song about current events. Bob Dylan told his audience, shortly before performing Blowin in the Wind for the first time, This here aint a protest song. No doubt some of the other songwriters included here will wince at the label, but I am using the term in its broadest sense, to describe a song which addresses a political issue in a way which aligns itself with the underdog. If it is a box, then it is a huge one, full of holes, and not something to be scared of.

But there are good reasons why the term is regarded with suspicion. Protest songs are rendered a disservice as much by undiscerning fans as by their harshest critics. While detractors dismiss all examples as didactic, crass, or plain boring, enthusiasts are prone to act as if virtuous intent suspends the usual standards of musical quality, when any music lover knows that people make bad records for the right reasons and good records for the wrong ones. The purpose of this book is to treat protest songs first and foremost as pop music. Not every song in the following pages is artistically brilliant but many are, because pop thrives on contradiction and tension. Electricity crackles across the gap between ambition and achievement, sound and meaning, intention and reception. So the best protest songs are not dead artifacts, pinned to a particular place and time, but living conundrums. The essential, inevitable difficulty of contorting a serious message to meet the demands of entertainment is the grit that makes the pearl. In songs such as Strange Fruit, Ohio, A Change Is Gonna Come, or Ghost Town, the political content is not an obstacle to greatness, but the source of it. They open a door and the world outside rushes in.

This is also a book about dozens of individuals, making certain choices at certain moments, for many different reasons, and with a range of consequences. In the worst cases, singers have been censored, arrested, beaten, or even killed for their messages. Less dramatically, there is the risk of looking shrill or annoying or egotistical. One popular canard about pop and politics is that people combine the two to get publicity, but if theres one thing the history of protest songs demonstrates its that there are far easier ways to shift a few extra records.

Its always a double-edged sword, says the former political songwriter Tom Robinson. If you mix politics and pop, one lot of criticism says youre exploiting peoples political needs and ideas and sympathies in order to peddle your second-rate pop music [and another says] youre peddling second-rate political ideals on the back of your pop career. Either way theyve got you. Some of the anti-protest-singer criticisms that Phil Ochs drily catalogued in the liner notes to his 1964 album All the News Thats Fit to Sing I came to be entertained, not preached to Thats nice but it it really doesnt go far enoughare still leveled today.

In many ways, writing a protest song is asking for trouble, and its this sense of jeopardy which gives the form its vitality. The songs in this book tend to stem from concern, anger, doubt, and, in practically every case, sincere emotion. Some are spontaneous outpourings of feeling, others carefully composed tracts; some are crystalline in their clarity, others enthralling in their ambiguity; some are answers, some just necessary questions; some were acts of enormous bravery, others the beneficiaries of enormous luck. There are as many ways to write a protest song as there are to write a love song.

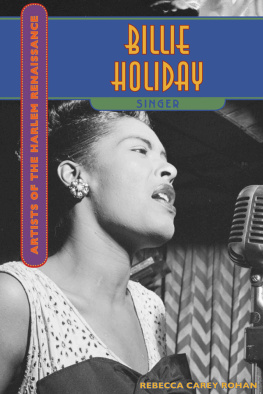

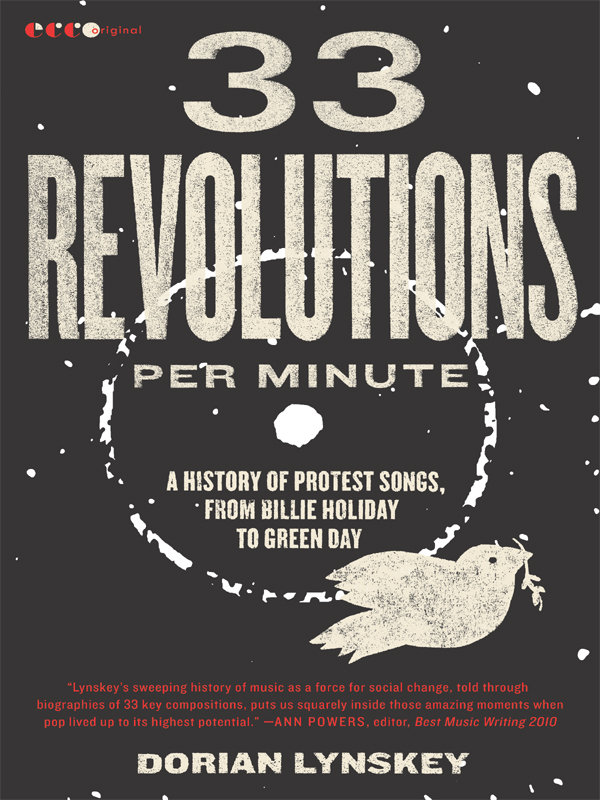

Of course, music has been used to make political or moral points for centuries (see appendix 1), but I have chosen to start with the intersection of protest singing and twentieth-century popular music because that, I think, is where things get interesting. In the United States before the 1930s, there was the apolitical pop music of Tin Pan Alley on the one hand and the borrowed melodies of labor songs on the other. Only when the pop song fully embraced politics, with Billie Holidays Strange Fruit, and folk music became radicalized, with Woody Guthrie, did sparks began to fly between the distinct poles of politics and entertainment. For reasons of space I have limited my focus to Western pop music, except (as in the case of reggae or Afrobeat) where they made a significant impact on Western audiences. That would be a whole other book.

For a while, in the dizzying rush of the 1960s, it was thought that pop music could change the world, and some people never recovered from the realization that it could not. But the point of protest music, or indeed any art with a political dimension, is not to shift the world on its axis but to change opinions and perspectives, to say something about the times in which you live, and, sometimes, to find that what youve said speaks to another moment in history, which is how Barack Obama came to be standing in Grant Park paraphrasing the words of Sam Cooke. Most of these stories end in division, disillusionment, despair, even death. On one level, everything fails; on another, nothing does. Its all about what people leave behind: links in a chain of songs that extends across the decades.