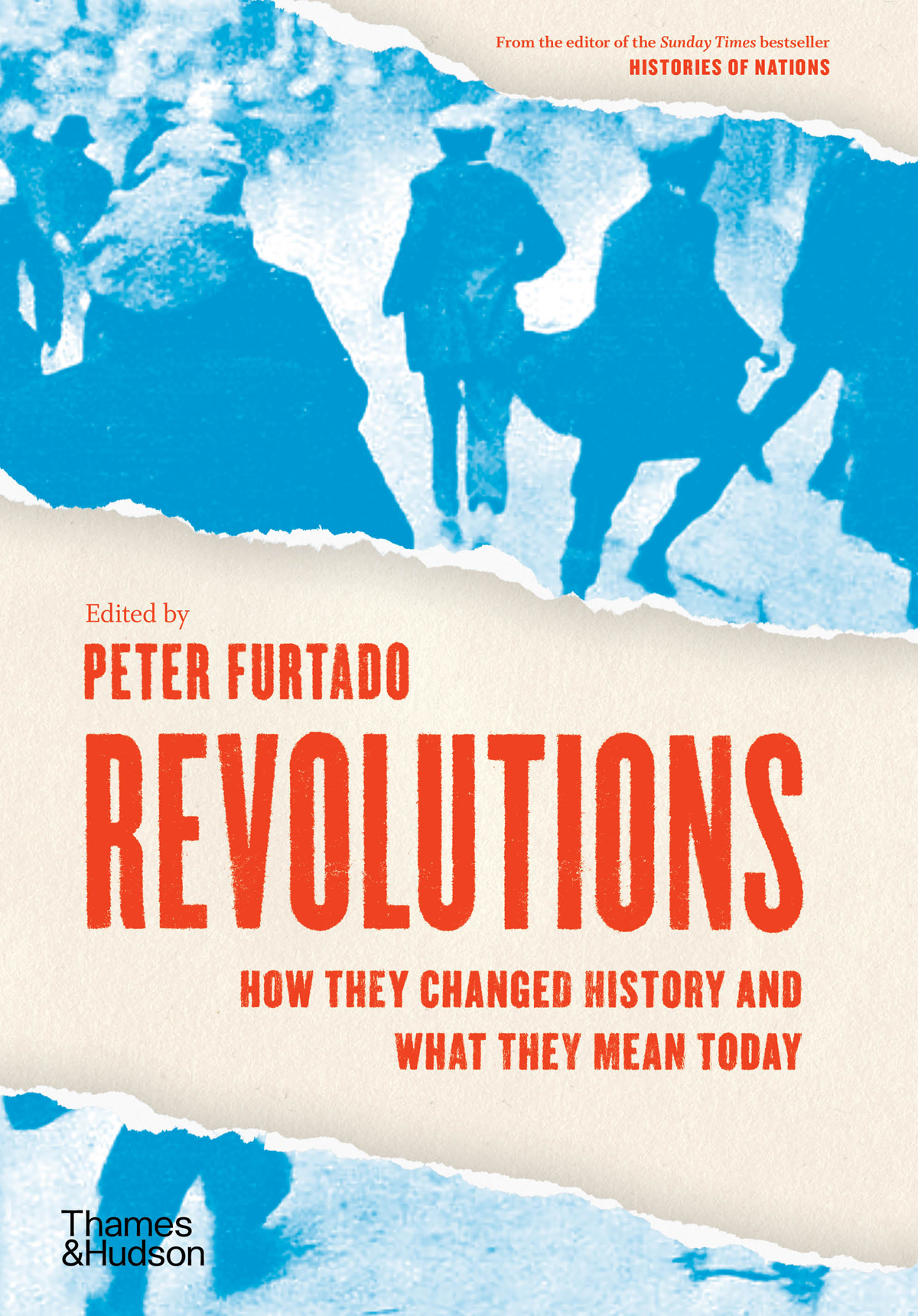

About the Author

Peter Furtado is the editor of bestselling books on world history told through multiple perspectives intimately connected to events and their legacies, including Histories of Nations: How Their Identities Were Forged, History Day by Day: 366 Voices from the Past and Great Cities Through Travellers Eyes, all published by Thames & Hudson. He is a devoted popularizer of history, the former editor of History Today and in 2009 was awarded an honorary doctorate by Oxford Brookes University for promoting history to the public.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Histories of Nations: How Their Identities Were Forged

Peter Furtado

People Power: Fighting for Peace from the First World War to the Present

Lyn Smith

I Object: Ian Hislops Search for Dissent

Ian Hislop and Tom Hockenhull

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

www.thamesandhudson.com.au

CONTENTS

Peter Furtado

Simon Jenkins

Ray Raphael

Sophie Wahnich

Bayyinah Bello

Axel Krner

Shin Kawashima

Mehmed kr Haniolu

Javier Garciadiego

Diarmaid Ferriter

Dina Khapaeva

Mihir Bose

Stein Tnnesson

Mobo Gao

Luis Martnez-Fernndez

Stephen Barnes

Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses

Sorpong Peou

Homa Katouzian

Mateo Cayetano Jarqun

Anita Pramowska

Vladimir Tismaneanu and Andres Garcia

Thula Simpson

Yaroslav Hrytsak

Yasser Thabet

O n the evening of 14 July 1789, King Louis XVI of France heard the news of the storming of the Bastille on his return from hunting. Notoriously he asked, Is this a revolt?, to which the Duc de La Rochefoucauld replied, No, Sire it is a revolution.

Less than a week later, the Duke was serving as president of the National Constituent Assembly, the body set up by the Third Estate (commoners) as an authority to challenge that of the king, and which thereby embodied the revolution he had predicted.

La Rochefoucaulds quote is famous for his perspicacity and for Louiss myopia; but what exactly did he mean? At the time, there were just two precedents considered worthy of the name revolution. One was the ousting of James II of England in 1688, and his replacement on the throne by his daughter Mary and her Dutch husband, William of Orange this was the so-called Glorious Revolution that created Britains constitutional monarchy, which in turn became the envy of the enlightened 18th century. The other was the overthrow of British rule in North America, establishing the republic of the United States in the 1770s80s. Both events certainly offered alarming precedents for Louis: ruling monarchs lost their crown or their claim to rule, in the face of widespread opposition reinforced by military muscle. Both were justified by a libertarian ideology that offered an alternative legitimacy to divinely inspired monarchy, and both became enshrined in institutions in England, the Bill of Rights; in America, the Constitution of the United States that changed the direction of their countrys history. These events were still resonating round the globe decades later.

This was what revolution meant on the day the Bastille fell. But during the next dozen years, the word acquired many other layers of meaning: the assertion of popular sovereignty and social justice, the sweeping away of oppressive institutions and corrupt privilege, a root-and-branch change in institutions and ways of thinking, the release of creative energy and imagination to escape the cruel stasis of a failed system; and also chaos, mob rule, the adoption of terror as a tactic to enforce the new order, and increasingly authoritarian government prepared to enforce social and political change at all costs.

In the following century, after Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels published the Communist Manifesto in 1848, revolution came to mean the overthrow of one class by another, the creation of a new society in which the workers own the means of production. This definition held sway throughout much of the 20th century with Marxist, MarxistLeninist or Maoist revolutionary movements in many countries across the world (and the sympathy of many intellectuals analysing their successes and failures).

The word revolution has also been applied, though usually in retrospect by historians or other commentators, to amorphous social, cultural or technological changes: the Industrial Revolution, the sexual revolution, the digital revolution. These are among the largest, most powerful drivers of all human history, with profound long-term consequences, but tend to result in less dramatic outcomes in the political arena, if no other.

Political revolutions have a similar reputation as events that inexorably force change within a particular country, though many revolutionaries seek to spread their message beyond geographical borders. The word, though, is too large, too capacious, to be owned by any particular ideology. Since the late 19th century there have been not just communist or socialist revolutions, but nationalist revolutions, democratic revolutions and constitutional revolutions too. There have been revolutions that have brought violence to millions of people, and others that were entirely bloodless; revolutions led by men and women with a lifelong commitment to bringing them about, and revolutions with no leaders at all, or with accidental or reluctant figureheads. Revolutions that made genuine, extended and sometimes successful efforts to improve the lot of the people, and revolutions that brought nothing but heartache and hardship.

The late 20th century saw one major popular revolution in favour of conservative theocracy (in Iran in 1979), and the popular revolutions in eastern Europe against the very workers states that Marxist regimes had themselves established. Since the late 1980s, the term revolution has more often been applied not to root-and-branch attacks on established values or the capitalist system, but to sudden popular surges to sweep aside dictatorships in the name of democracy to establish human rights and personal freedoms. Unlike Leninist or Maoist revolutions, these have been welcomed by the people with their hands on the worlds levers of power at least so long as they pose little threat to established commercial or geopolitical interests. Yet even when modern revolutions have succeeded in their original aims of ousting tyranny, their longer-term outcomes like those of many earlier revolutions may still prove ambiguous, or worse.

The word itself was first applied to radical political change within a polity only in the 17th century, though it did not yet carry the meaning that La Rochefoucauld understood. Although the execution of King Charles I and establishment of an English republic in 1649 may look revolutionary to us, contemporaries preferred to call this the Great Rebellion and ascribed the name revolution only to its aftermath: the restoration of Charles II in 1660 and then to the expulsion of his unpopular brother James in 1688. It is with those events that this book begins.

Revolution may be hard to define in the abstract; yet people generally believe they can recognize one when they see it. A revolution is often contrasted with a rebellion not only in that a revolution succeeds in its immediate aims, whereas a rebellion probably fails, but in its choice of aims as well. The rebel typically seeks autonomy from the tyrant, whereas the revolutionary seeks to overthrow him. The revolution releases a heady sense of liberation, an urgent and sudden change like the opening of a dam (most revolutions are preceded by a long period of political stasis, usually combined with a building sense of injustice based on structural imbalances such as an increase in population or economic downturn, exacerbated by anger at the corruption of those in power). And this intoxicating liberation can be powerfully felt across time and space: the extraordinary creativity of the early Bolshevik Revolution the art of Vladimir Tatlin and Kazimir Malevich, the films of Sergei Eisenstein, the music of Dmitri Shostakovich was echoed in the creative hothouses of the Mexican revolution, the Cuban and others.

Next page