for my daughter, Sapphira

Contents

Guide

T he year is 2002, I am twenty-eight years old, and I am sitting in a small, unfamiliar hotel room hooked up to a lie-detector machine.

Pneumo tubes are wrapped firmly around my chest to measure my respiration, a tight armband sphygmomanometer measures my blood pressure and a clip pinching the end of my index finger measures tiny changes in my perspiration. Standing over me is a journalist from the Australian newspaper. Across the table is a professional polygraph examiner a former Victorian police officer who normally tests suspected paedophiles, rapists and killers. He is testing me to see whether or not I actually write my own books.

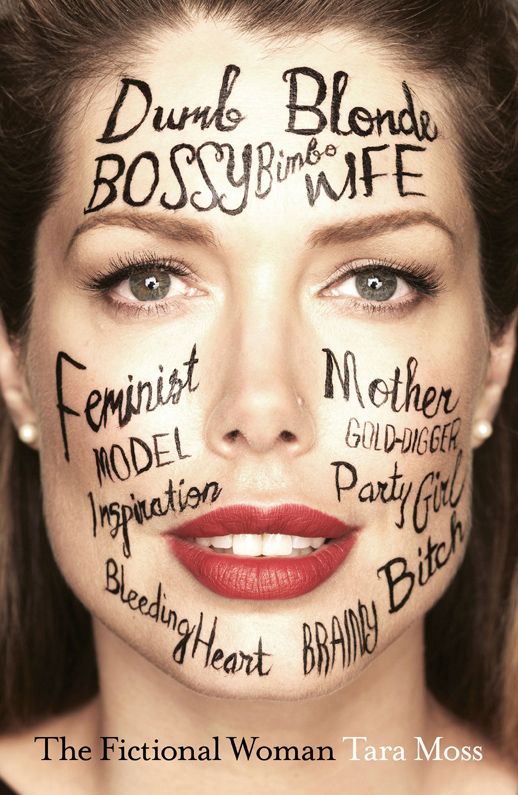

I worked as a photographic and catwalk model in North America, Europe and Australia before quitting at age twenty-five and publishing my debut crime novel. Two and a half years later, as my second novel hits the shelves, the book itself has seemingly been overshadowed by a more compelling mystery: how a model-turned-author (as Im frequently dubbed in the press) could possibly write a book.

The rumours abound: that my novels are heavily edited; that my boyfriends wrote them for me; that I employed a ghost writer; that they are plagiarised. But the truth is, I have written every day since I was a child, and I have spent hours every day for years now plotting, researching, writing, editing and labouring over my novels. The rumours are false, but without a strong public voice (social media is yet to exist) I have very little means to defend myself. So when a call came from a journalist asking if I would take a polygraph test to prove that I write my own novels, I replied without hesitation: Bring it on.

More than a decade later, the lie-detector test that became a defining moment in my early publishing career feels like the experience of some other woman. At forty, the struggles of my twenty-something self to be given credit for writing my own words has been largely forgotten. I am now the author of nine novels, a blogger and freelance journalist, a doctoral candidate, happily married and the mother of a young girl. The thirty-page document confirming that I am indeed the author of my own work collects dust in a corner cupboard.

Over the years I have become a big believer in statistics and empirical research. This, I suspect, is the lesson I have learned from my polygraph test: that sometimes cold, hard facts are the only way to break through unfounded assumptions my own assumptions as well as those of others. They help us to see beyond the biases formed by our own experiences to larger patterns in the world.

Here are a few statistics that grab me at the moment:

Women comprise 50.2 per cent of Australias population, but as of 2014 they make up less than one-third of all parliamentarians and occupy roughly 5 per cent of all Cabinet positions.

About 70 per cent of front-page by-lines in Australian newspapers belong to male journalists, despite the fact that an equal number of men and women are employed as journalists.

During six months of US election coverage in national print, TV broadcast and radio outlets, 81 per cent of statements about abortion were made by men.

As of 2010, the National Gallery in the UK had 2300 works in its collection, of which ten were by women.

In the top-grossing 250 films of 2012, 91 per cent of directors were men, as well as 85 per cent of writers, 83 per cent of executive producers and 98 per cent of cinematographers. In 2013 the top ten male actors combined made over 2.5 times more than the top ten female actors combined.

Women working full time in Australia earn, on average 17.5 per cent less than their male counterparts.

Perhaps my interest in these statistics stems simply from the lived experience of being a woman, or from the fact that I now have a daughter and I want her to have opportunities and a voice. Perhaps my interest in womens representation and the lack of celebrated female writers, journalists, directors, cinematographers and artists stems from my personal experience of fictions about certain types of women (models, blondes) and the stark disconnect I once experienced between the real and the fictional me and by extension, I imagine, the disconnect between the representations of other women and the reality of who they are. Perhaps my interest in womens representation in parliament (and non-white representation, and non-heterosexual representation) stems from an interest in seeing a more equitable representation of the community in the parliamentary processes of our democratic country. Whatever the reason, I have taken notice of these facts.

I have also noticed something else: a large number of people are dismissive or even aggressive when confronted with statistics like those above. Women are accused of playing the gender card. Time and time again we are told that advancement in our society depends solely on merit and hard work, that everything is equal now, that gender doesnt matter. But as long as one gender continues to be paid less, represented less, and continues to be consistently less involved in parliamentary decision making and public debate (even when it is about their own bodies), we have to conclude that, unfortunately, gender does still matter.

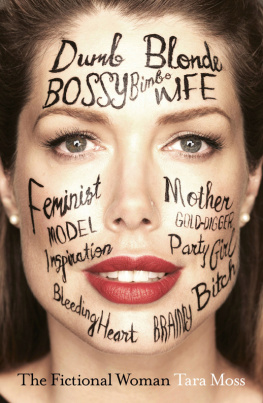

There are many important discussions to be had about our society and the world at large: discussions about the issues facing our children, our seniors, our environment, and the circumstances of those from different cultures and countries. (Some of which I also write on.) But this book is focused unapologetically on the experience of women and girls, within the culture I know best. Despite its title, The Fictional Woman is a work of non-fiction. Many of my arguments are based on statistical and media analysis empirically supported facts and figures and much of the book draws on personal experiences I have never written about before, some unpleasant for me to recall and some a joy. Some of the dates are guesses. All of the stories are true.

And I wrote them myself. The results of the lie-detector proved unequivocally that (shock!) I am a writer.

How ironic this all is. Im hired for my looks, and yet it takes them three hours to make me pretty enough to photograph. Isnt that weird?

Supermodel Monika Schnarre, at age 15

I t was the first day of summer, and I was sitting in the front passenger seat of the family car sipping a Dairy Queen milkshake. The cold of the milkshake froze the metal braces on my teeth, so I had to remember not to drink it too fast. My mother, Janni, was in the drivers seat. We were parked at the scenic lookout at the top of Mount Tolmie, my hometown of Victoria, British Columbia, spread out below us.

My mother put down her own milkshake and took my hand. Tara, is this what you want? she asked, looking me in the eye. She was not referring to the milkshake, but to the sudden, rather staggering suggestion that I become an international fashion model.

In many ways, I was the most unlikely candidate for a model you could imagine. Throughout my childhood I was what many people refer to as a tomboy. I loved climbing trees and playing with toy cars. It wasnt that I hated feminine things; I just liked cars and horses and spaceships things that could go fast and take you to exciting places and planets more than I liked toys that needed to have their hair brushed. I preferred toy monsters to toy kitchen sets. My parents never emphasised that I was different or needed to change my preferences; these choices of mine were not conscious, at least not yet. And I didnt have a problem with girls clothes per se; I just hated wearing dresses because they got in the way when I was going places, like up trees.